Christopher Jones (l. c. 1570-1622 CE) was the English captain and quarter-owner of the Mayflower, the cargo ship that brought the religious separatists (now known as pilgrims) to the New World in 1620 CE. Little is known of Jones' life prior to the Mayflower expedition – and even afterwards – other than what is recorded in legal documents on where he lived, conducted trade, married, and the births of his children. He is described by the Puritan pilgrim William Bradford (l.1590-1657 CE) as an affable and easy-going man who, unlike others of the crew of the Mayflower, was respectful and helpful to the passengers.

Jones was contracted by one Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c.1647 CE) to transport the religious separatists of Leiden, the Netherlands (formerly English subjects) to a destination above the thriving Jamestown Colony of Virginia and below the Hudson River Valley of present-day New York in North America. Although Jones was an experienced mariner, the rough weather of the Atlantic Ocean in the fall of 1620 CE blew the ship off course and they landed instead in Massachusetts near the site of modern-day Provincetown; the pilgrims would establish the Plymouth Colony across the bay in November 1620 CE.

It was Jones' plan to return to England as soon as he had disembarked the pilgrims at their settlement, but sickness among his passengers and crew – 50% of whom would not survive – kept him anchored off Plymouth for the winter of 1620-1621 CE. The ship served as a home to the passengers while the settlement was being built. He finally left for the return voyage in April of 1621 CE and continued as a trader, transporting goods primarily between England and France, until his death (from causes unknown but thought to be related to his expedition to the New World) in 1622 CE. In 1624 CE, the Mayflower was sold for scrap and dismantled.

Early Life & Trade

Christopher Jones, Jr. was the son of Christopher Jones Sr. and Sybil Jones of Harwich, Essex, England, born c. 1570 CE. His father was involved in maritime trade and part-owner of the ship Marie Fortune. When his father died in 1578 CE, his will stipulated that his son would inherit his share of the ship, and this, presumably, was kept in trust for him by his stepfather, Robert Russell, who married Sybil after the elder Jones' death.

Jones married one Sara Twitt, with whom he had grown up as she lived across the street from him, in 1593 CE when he was around 23 years old and had been working aboard ships since before his 18th birthday. He and Sara had one son, Thomas, who died in 1596 CE, and Sara would die in 1603 CE. Shortly after this, Jones married Josian Gray, a widow at the age of 19, whose family was also involved in maritime trade. The couple had four children while continuing to live in Harwich and four more once they moved to Rotherhithe-on-Thames, London in 1611 CE. Jones would name one of his first ships Josian in honor of his wife.

He seems to have been a prominent citizen of both Harwich and Rotherhithe and his trade was primarily in wine from France (the Bordeaux region) in return for textiles from England. He had acquired enough wealth by 1605 CE that he could afford hunting dogs, a detail of his life only known because he was fined for it; only the upper-class were allowed to own and use hunting dogs at this time, and no one but the nobility and their guests could engage in “chases” for game with dogs.

In 1609 CE, he may have sold the Josian and his interests in other ships to become a quarter-owner of the cargo ship the Mayflower. He is registered as the Master (captain) of the Mayflower for that year and again in 1611 CE after an expedition to Norway. Primarily, he supplied wine from France to the upper-class of London as well as transporting other commodities between England and France in quick turn-around trips which could be accomplished with relative ease for significant profit. He had experience sailing on the open sea, however, as established by records noting him as captain on the Norway expedition as well as others to the Mediterranean region.

The Mayflower Contract

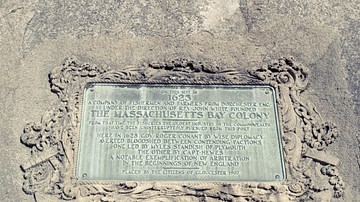

In 1620 CE, the Mayflower was rented by Thomas Weston in the interests of a group of religious separatists of Leiden, the Netherlands, for their transportation to the New World. Weston was a merchant-adventurer, a profession which had become established after the success of the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, who matched potential expeditions with investors and put together legal contracts promising a return on investment once the settlement was established.

In this case, he obtained a charter in the name of the Virginia Company of London for Jones to transport the separatist congregation to a region in North America above Jamestown – though not close enough that they would be a part of that colony – in the area of the Virginia Patent which, at that time stretched north to the Hudson River Valley region of present-day New York State, claimed by the Dutch since 1609 CE. The agreement with Weston stipulated the passengers of the Mayflower were to be set ashore in a region already settled where they could expect help if they should need it but would have space to establish their own colony.

Mayflower Voyage

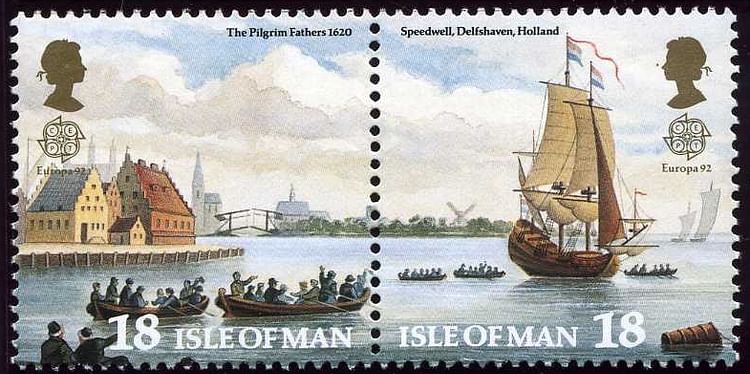

The Mayflower had never been across the Atlantic Ocean before. It was a 12-year old cargo ship, never intended for passengers, of the carrack type, three-masted atop three decks – main, gun (also known as `tween deck), cargo hold – with a castle fore and aft. It measured approximately 100 feet (27 m) long and 25 feet (7 m) wide with 8 small cannons and 4 medium cannons on the gun deck. The crew was quartered in the forecastle and the captain aft, assorted supplies sometimes carried on the gun deck and cargo in the hold. On this trip, however, 102 passengers would be quartered on the gun deck after the Speedwell leaked and was abandoned as unfit for the voyage.

The problems with the Speedwell delayed departure, which should have been in July of 1620 CE, until September, and by this time, the Atlantic was considerably more difficult to manage than it would have been earlier. The waves were high and the wind strong, blowing from the west, the direction the Mayflower was sailing, requiring Jones to zigzag his way across the sea instead of making a straight sail. Scholar Jonathan Mack describes the conditions:

The taut rigging hummed, and the wooden ship groaned and creaked. With seas coming over the ship's sides, the ports [windows on the gun deck] were closed. The living area turned dark, and the smells of 150 unwashed people and rotting food intensified. The forces of wind and sea were strong enough to bend the Mayflower's stout planks, and her upper works started leaking. Water also came up and over the side as waves buffeted the ship and sloshed around on the main deck, which was the roof over the heads of the passengers in the 'tween deck's living area. As the ship heaved and banged, the seams in the deck opened and water poured onto the heads of the colonists. At one point, a strong gust of wind or an odd wave shook the Mayflower so fiercely that one of the huge beams supporting the main deck bowed and split under the pressure. Between leaking water and the broken beam, the passengers rightfully became alarmed that the vessel might not be able to continue. (64-65)

At this point, the Mayflower was in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean; turning around or continuing on were equally risky, and it was ultimately up to Jones to make the decision. After inspecting the ship and the damaged beam, Jones decided the ship would hold, and they should continue on, but the beam would have to be repaired. No one knew how this could be accomplished, however, until one of the colonists produced a large screw he had brought along in case he needed it in the New World. With the screw and extra timber aboard ship, the beam was fixed and the planks then recaulked.

The Mayflower sailed on into the winds which continually blew the ship sideways and were so powerful they strained the masts at full sail. Concerned that the masts might snap, Jones ordered the sails furled and tied but, as Mack comments, in taking down the sails, “a new dilemma presented itself: the force of the wind on the sails is what gave the Mayflower the ability to steer” (65). Without steerage, the ship could not hold a course and, more significantly, might capsize in the rough seas. Mack describes Jones' solution to the problem:

Faced with this increased danger, Jones decided upon an extraordinary measure. He ordered that all the sails be furled and lashed tightly to the yards. Everything on deck was secured, and the hatches were covered. Jones then turned the ship into the wind, a maneuver known as lying ahull. Rising some twelve or so feet above the main deck in the aft-most part of the ship was the master's cabin and the poop deck. With the ship facing into the wind, the superstructure at the back of the ship would act as a kind of wooden sail, helping maintain some modest amount of steerage that allowed the helmsman to keep the ship's beam from being hit broadside by the piling waves. (66)

Jones' plan worked and the Mayflower continued on its voyage, sighting land at last on 9 November 1620 CE. Jones recognized at once that they were nowhere near their destination but was unsure where exactly they were. Scurvy had broken out on the ship, and the passengers were eager to land, but Jones was under contract to deliver them to a certain site and could not just drop them off in the middle of nowhere. He, therefore, set a course due south along the coast, but more rough weather and dangerous shoals made him turn about, and the Mayflower coasted back into the bay near Provincetown. After scouting the area for the best landing site, the ship dropped anchor off of what would become Plymouth on 11 November 1620 CE.

Jones & the Pilgrims

The 102 passengers aboard the Mayflower were not all religious separatists of the Leiden congregation but included those hired by Weston to help establish a profitable settlement or those who had come for their own purposes. These people were referred to as Strangers (those not of the faith) by the pilgrims. Prior to disembarking, all 41 males, pilgrims and Strangers alike, signed the document known as the Mayflower Compact, an agreement that all would obey the laws voted on by the men of the community for the common good. This was necessary because they would be disembarking in a land under no law and therefore had to create their own. Further, since they would not be landing near any other European colony, they had only each other to rely upon and it was understood that none of them would survive unless they all worked toward a common goal.

There was nothing he could do, however, to stop the spread of scurvy and other diseases, which, along with malnutrition and exposure, would kill 50% of the passengers and crew during the winter of 1620-1621 CE. Jones bore witness to the will of the cobbler William Mullins (l. c. 1572-1621 CE), father of Priscilla Mullins (l. c. 1602-1685 CE), and brought it back to London to be recorded (the only surviving will of a Mayflower passenger today), thus securing land in Plymouth for Mullins' son who was still in England. He would also transport letters, books, and other objects for the pilgrims when he finally left in April of 1621 CE.

Prior to that, however, he kept the Mayflower at anchor off Plymouth, providing the passengers with shelter while they built their colony. The Mayflower also served as a kind of floating fortress, which dissuaded the natives of the area, especially the Nauset tribe, from attacking the passengers again, as they had earlier in December 1620 CE during the so-called First Encounter.

Conclusion

Jones left on the return trip once his remaining crew had regained their health and the pilgrims had established themselves on land. He replaced the ballast in the ship with stones from around Plymouth, gathered the legal documents and personal letters and artifacts, and completed the trip in only 33 days, half the time it had taken him to bring the colonists to the New World against the wind.

The Mayflower arrived back in England in May (given as either the 5th or the 9th), and by October 1621 CE, Jones was back to his old trade runs to France. He fell ill and died on 4 March 1622 CE and was buried on 5 March in the churchyard of St. Mary's of Rotherhithe. His grave was no doubt initially marked, but its location was lost during a renovation of the building and grounds in 1715 CE. In 1995 CE, a memorial to Jones was erected at the church and another in 2004 CE.

The Mayflower remained docked on the nearby Thames River after Jones' death and had succumbed to dry rot by 1624 CE when it was legally declared to be in a state of ruin. It was then the property of the three surviving owners and Christopher Jones' widow Josian who sold it for scrap for approximately 130 pounds sterling. The fate of the ship's remains, as well as the site of the grave of her captain, are still debated, but Christopher Jones and the Mayflower have been immortalized in the stories of the crossing of 1620 CE and the establishment of the Plymouth Colony in the New World.