Kanadehon Chushingura (A Treasury of Loyalty of Loyal Retainers or The Story of the Forty-Seven Samurai) is the most popular play in the history of Japanese theatre, first performed in 1748. It is a work of fiction, but the details of the story are often confused with those of a real event, the Ako Incident (1701-3), on which it is commonly thought to be based.

Rise of the Puppet Theatre

After the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate at the beginning of the 17th century, peace came to Japan after a century and a half of civil war. The population quickly rose, and towns expanded. Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and Osaka especially grew rapidly, and in these cities, a new kind of urban culture developed that reflected the values of the townspeople. Included in this were two new forms of theatre. One was kabuki, which used actors, and the other was bunraku, a form of puppet theatre. In the European tradition, puppets are thought of as being children's entertainment, but in Japan, puppet theatre developed as a highly refined art form.

In its mature form, bunraku uses puppets that are about half the size of real people and have facial features that can move. Three performers, dressed in black to indicate that no attention should be paid to them, manipulate the puppets on the stage. At the side of the stage sits a person who recites the story, including all the dialogue, to the accompaniment of a musical instrument called a shamisen. Although both kabuki and bunraku are now thought of as 'classical' theatre, in the Edo period, they provided people with popular entertainment much as TV dramas do today.

Golden Age of Bunraku

The most famous playwright at this time was a man called Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724). He wrote two different kinds of plays. Jidaimono were historical plays, usually based on well-known events from the Japanese past. For the content of these plays, he drew heavily on legends and stories from classical Japanese literature, such as Japanese war tales. For example, he wrote twelve plays based on the Soga Monogatari alone. This 13th-century war tale describes how the two Soga brothers spent 17 years seeking revenge against the person that murdered their father.

In contrast to the historical dramas were sewamono, domestic dramas that centred on events in the lives of ordinary people living in the present day. In this genre, he wrote quite a few plays about 'love suicides' in which couples ended up killing themselves because they could not be together for one reason or another. The most famous of these were Sonezaki shinju (The Love Suicides of Sonezakli, 1703) and Shinjuten no Amijima (The Love Suicides of Amijima, 1721). From the 1710s, there was a trend towards combining these two genres together. A play would be based on some historical person or event, but it would also include romantic episodes of the kind that appeared in domestic dramas. No attempt was made at historical accuracy in these plays as they were simply intended as entertainment.

In the 1740s, the playwriting team of Takeda Izumo (1691-1756), Namiki Sosuke (1695-1751), and Miyoshi Shoraku (1696-1777) produced three of the greatest bunraku plays:

- Sugawara denju tenarai kagami (Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy, 1746), recounting the life of the Heian period (794-1185) courtier and scholar Sugawara no Michizane (845-903)

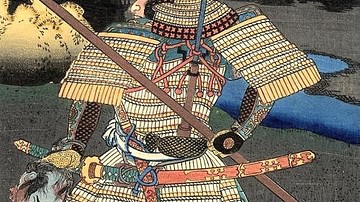

- Yoshitsune senbon zakura (Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees, 1747), on the life of Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189), a warrior that lived in the 12th century.

- Kanadehon chushingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, 1748), a story set in the 14th century at the time of the dispute between the Northern and Southern Courts.

Chushingura

The setting, characters and basic plot for Chushingura are based on a story that appears in the Taiheiki, a war tale written at the end of the 14th century. That story relates how the deputy to the shogun Ashikaga Takauji, Ko no Moronao, a man famous for his greed and lechery, lusted after the wife of a provincial warrior called En'ya Hangan. When she rebuffs him, he tells Takauji that Hangan is planning a rebellion. Hangan tries to escape back to his home province with his family but is pursued by Takauji's men. Hangan's wife is killed, and he commits seppuku (ritual suicide). Before dying, he prays that he will be reborn seven times so that he can become the enemy of Ko no Moronao again and again.

In Chushingura, this story is embellished in the following way. Ko no Moronao pursues the wife of En'ya Hangan. She rejects him, but her husband is provoked into violence against Moronao. The shogun orders Hangan to commit seppuku as punishment, which he promptly does. Hangan's chief retainer, Yuranosuke, spends many months secretly plotting with his fellow warriors to get revenge on Moronao. Finally, they make a night attack on his mansion and kill him. They march to the temple where Hangan is buried and make an offering of Moronao's severed head. The play ends with the conspirators preparing to kill themselves by seppuku, satisfied that they have demonstrated their loyalty to their deceased lord by getting revenge on Moronao.

As was common at the time, the playwrights injected some elements from a real contemporary event in to the story to make it more interesting. In this case, they used details from the Ako Incident, which had taken place in the period 1701-3. In 1701, the Lord of Ako, Asano Naganori, attacked an official called Kira Yoshinaka within Edo Castle while preparing for a court ceremony. Kira was only slightly injured, but disturbing the peace in this fashion was a capital offence. Asano was ordered to commit seppuku. His domain was also confiscated, and his retainers became ronin or masterless warriors. Subsequently, Asano's chief retainer, Oishi Yoshio, organized a secret plot against Kira because he believed he was responsible for the death of Asano. Two years later, he and his followers carried out a surprise attack on Kira's mansion in Edo and killed him. His severed head was taken to Sengokuji Temple where Asano was buried. There the plotters waited until the authorities arrived. They were arrested, and, after an investigation by government officials, they were also ordered to commit seppuku.

As can be seen from this brief summary, some of the key aspects of the plot in Chushingura are derived from the Ako Incident. These include the chief retainer hatching a secret plot to get revenge; the night attack on their adversary's mansion; and the march to the temple where their enemy's head is presented as an offering. There are other similarities. The number of participants in both attacks is the same, and the names of many of the characters in Chushingura closely resemble those in the Ako Incident. These similarities have led critics to think of Chushingura as being a thinly disguised portrayal of the Ako Incident. It was set back in the 14th century, they argue, to avoid government censure at a time when the portrayal of events involving the ruling warrior class was prohibited in the theatre. While there is some truth in this view, it also obscures the fact that there are very important differences between what happened in the Ako Incident and the story in Chushingura.

Differences Between the Ako Incident & Chushingura

In Chushingura, Ko no Moronao is a villain because he makes advances on En'ya Hangan's wife. Hangan is a victim because he is forced to kill himself as a result of this. In the Ako Incident, however, it is not actually known why Asano attacked Kira. There is no evidence that Kira was a bad person or that he had done anything wrong. Asano was not the victim, but, in fact, the perpetrator of the attack that started the incident. Also, Asano was ordered to commit seppuku not by Kira, but by the government. In this situation, a revenge attack would not seem justified. Also, in the case of the Ako Incident, it is not actually known what motivated the revenge attack. Only 47 of Asano's 300 retainers participated, and, at the time, Japan had been at peace for more than a hundred years, so such things were unheard of.

Secondly, Chushingura ends just as the warriors are about to kill themselves by seppuku. Through this, they show themselves as heroes willing to sacrifice their own lives out of loyalty to their dead lord. In the case of the Ako Incident, however, the warriors did not kill themselves. They waited for the authorities to arrive and arrest them. They only committed seppuku when they were ordered to do so by the government many months later. Rather than being heroes, they were executed as criminals. At the time, the conspirators were criticized for this. Some said that, if they were true warriors acting out of loyalty, they would have committed seppuku on the spot as soon as the revenge attack was complete.

Thirdly, Chushingura contains a number of subplots of the kind that appeared in the domestic dramas. These are all completely fictional but are intended to reinforce the main theme of the play, people's willingness to sacrifice their lives out of a sense of duty and loyalty. One example of this is a retainer of Hangan's called Kanpei. He was absent when Hangan died and wants to kill himself out of remorse, but his wife, Okaru, talks him out of this. Okaru later agrees to be sold to a brothel to raise money so that Kanpei can join the vendetta. Later, he mistakenly believes he has killed Okaru's father who is returning from the brothel with the money. Members of the vendetta come to Okaru's house to return Kanpei's money because they believe it had been gained immorally. Out of shame, Kanpei commits seppuku, but, before dying, he tells his version of the story saying that the death of his father-in-law was an accident. Convinced of Kanpei's honesty, they pull out the scroll containing the signatures of those committed to the vendetta, and Kanpei adds his to the list. He dies happy knowing that his name is included amongst those planning to carry out the vendetta. These kinds of fictional embellishments are one of the main features of Chushingura.

After its first performance, the play was an outstanding success. Different versions were performed any number of times, and it was quickly adapted for the kabuki theatre. While the details of the real Ako Incident were little known even at the time, the fictional version contained in Chushingura became famous. As a consequence, people began to believe that what was in the play was an accurate of a real historical event. This process was greatly enhanced when later versions of the play dropped the original 14th-century setting and set it at the time of the Ako Incident in the early 18th century and also began to use the names of the real Ako plotters. This is the way the Chushingura story is usually presented in movies and on TV today.

One reason Chushingura remains popular is that people believe it is based on a real event. The idea of heroic individuals willingly sacrificing their own lives out of a sense of justice and loyalty conforms to the popular, although mythical, image of Japanese warriors. It is important to remember, however, that, while the story does contain elements derived from the Ako Incident, it is mostly a work of fiction.