Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 to c. 170 CE) was an Alexandrian mathematician, astronomer, and geographer. His works survived antiquity and the Middle Ages intact, and his theories, particularly on a geocentric model of the universe with planets following orbits within orbits, were hugely influential until they were replaced by the heliocentric model of the universe proposed by Copernicus and Galileo.

Life & Works

Ptolemy, also known as Claudius Ptolemaeus (or Klaudios Ptolemaios), was born around 100 CE, but biographical information on him is scarce indeed. All that is really known is where (Alexandria) and when (125 to 141 CE) Ptolemy took certain astronomical observations and in which order he wrote his main treatises. Ptolemy's ideas, in contrast, became widely known and were adhered to for centuries. Ptolemy's theories were perpetuated through his surviving texts, which include Mathematikê Syntaxis (Mathematical Composition), more frequently called by its Arabic name Almagest (meaning "The Greatest Book"); Planetary Hypotheses; Tetrabiblos (aka Apotelesmatika); Harmonics; Optics; and Geôgraphikê Hyphêgêsis (Geography). These various titles illustrate the breadth of Ptolemy's intellectual inquiry.

Ptolemy's works found their way from the ancient Mediterranean to the Islamic world (translated into Arabic in the 9th century), the Byzantine Empire, and then back to Europe in the Middle Ages (translated into Latin in the 12th century). The Almagest was first issued using the printing press in 1515. Ptolemy's theories were only seriously challenged and then replaced in the 17th century during the Scientific Revolution.

The Almagest

The Almagest is Ptolemy's most famous work and was likely completed around 150 CE. It is a sort of textbook consisting of 13 volumes, which cover his own theories and plenty of ideas of earlier thinkers regarding the movements of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets. He extended the ideas of Almagest in his Planetary Hypotheses.

Ptolemy was a keen astronomer, although he was reliant on the naked eye since the telescope was not invented until the early 17th century. What Ptolemy did have access to were masses of astronomical observations taken by ancient Babylonian scientists from the 8th to the 3rd centuries BCE. He also had access to similar readings taken by Greek astronomers from the 5th century BCE up to his own time. A third source was those observations he recorded himself, mostly at Alexandria between 127 and 141 CE. Finally, Ptolemy draws on the theories of earlier thinkers, notably the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) and the Greek astronomer Hipparchus of Nicea (c. 190 to c. 120 BCE).

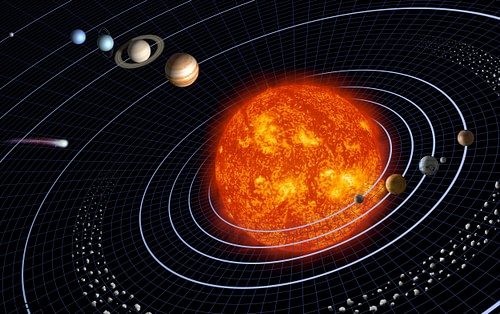

In Ptolemy's model of the universe, Earth was considered the centre of the cosmos, with the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars revolving around it in uniform circular orbits as they travel through a substance labelled aithêr. It was crucial for most thinkers to have the Earth as the centre of the universe because of the importance they gave humanity in their view of the cosmos. In Ptolemaic astronomy, after the central Earth, there is (in order) the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and then the stars.

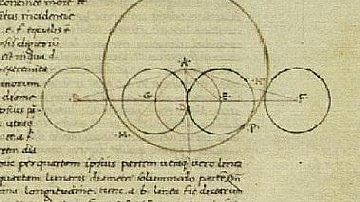

Ptolemy attempts to measure the motions of the heavenly bodies, and by doing so in complex tables, it is possible to predict their future movements and both solar and lunar eclipses. One of the problems Ptolemy (and his predecessors) had was that it is possible to observe that the heavenly bodies do not move in regular circles or at a regular speed compared to Earth. A theory was developed to explain these facts, namely that a body like the Moon travelled in a smaller perfect circle (an epicycle) that itself follows the track of a larger circle (the deferent) which revolves around the Earth. For the Sun, the orbit is slightly off-centre (compared to the fixed central point, the equant), and so as the Sun moves around the Earth, it appears to move closer and then further away when actually it is still following a perfect circle. Epicycles also explain why the planets can be observed to move backwards for a short time, their retrograde motion. This was all something of a clever fudge of an explanation, but it illustrates that, for ancient thinkers (and many medieval ones), it was necessary for planetary orbits to be perfectly circular as this reflected what was considered the perfection of Creation (and so the Creator). Aristotle had created his view of the cosmos based on perfect spheres, and Ptolemy fitted his theories into that viewpoint. There was, though, the problem that bodies moving around in an off-centred orbit would eventually hit each other. These preconceived ideas of circular orbits with the Earth at the centre of things took 15 centuries to shake off and so allow astronomers to explain what is observable.

Ptolemy continued to build upon what turned out to be an entirely wrong theoretical foundation by explaining the movement of the stars. Ptolemy meticulously catalogued 1,022 stars (those visible from Alexandria), all grouped into their various constellations where possible. These stars, he said, were fixed in relation to each other, but the entire field of stars, fixed in a sphere, moves around the Earth in a very slow process he described as 'procession'. Another problem, presented in Planetary Hypotheses, was to consider what the universe is actually made up of, that is, how do the heavenly bodies move around in such a regular way. Ptolemy adapted from earlier thinkers a system of nested spheres or, as the historian J. Evans puts it, "a sort of cosmic onion" (Bagnall, 884) in which "each body's 'sphere' is contiguous to the next" (Hornblower, 1236). In other words, the heavenly bodies are not floating but are fixed in a system of interconnected spheres which determines their path through the universe.

It is here important to remember that it was Ptolemy's mathematical tables and catalogue of information on the stars which were considered most useful by contemporary and later astronomers. Ptolemy's theories as to why or how heavenly bodies moved were far less relevant than the measured observations of their movements. This is just as well because although Ptolemy's theories fit the observable facts, alas, they were entirely wrong in many cases. Even more significantly, the errors were adopted as gospel by just about everyone, including the Christian Church, which rather liked the idea that God's creation, the Earth, was at the very centre of things. To challenge Ptolemy and Aristotle's view of the cosmos became nothing short of heresy. There was another consequence of the dominance of Ptolemy's ideas, and this was "the loss of all earlier works on similar topics" (Hornblower, 190). Ptolemy's model was far from perfect, but it was the only one to survive intact from antiquity.

Geography & Other Works

In later works, notably Tetrabiblos, Ptolemy presents a theory that the movements of celestial bodies have effects on earthly matters (for example, the weather), and these can be predicted thanks to astrology. In his Harmonics, Ptolemy developed a model where whole numbers and their ratios are equated with musical scales. Optics discusses how the human eye works. Ptolemy believed the eye sends out cones of perception which strike the object, and the soul somehow reads this information to determine shape, size, colour, and so on.

Ptolemy was very interested in cartography and ambitious enough to want to create a world map. Ptolemy's 8-volume Geography drew on the work of earlier geographers, notably Marinus of Tyre (early 2nd century CE), and contains an impressive catalogue of over 8,000 places identified by their longitude and latitude. This information was designed to help anyone make their own map of the world. The known world was limited at the time, of course, and Ptolemy did make a number of errors, such as making the Mediterranean Sea too long (due to inaccurate astronomical data) and having the Indian Ocean as an inland sea bordered by India, Africa, and a great southern continent. Ptolemy tried to solve the problem of how to represent three-dimensional land masses on a two-dimensional map and keep their relative size and position to each other as close to reality as possible. He endorsed the idea that a true global map should be projected onto a sphere. For all its errors, "Geography was a remarkable achievement for its time, and became the standard work on the subject (revised innumerable times) until the 16th century" (Hornblower, 1237).

The Copernicus Revolution

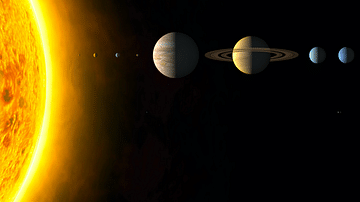

Ptolemy's views held sway over astronomy for centuries, but one man did eventually challenge the Ptolemaic model, the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543). From around 1514, Copernicus believed that Earth was a planet which orbited around the Sun, the real central point of our solar system. The Earth turning on its own axis and orbiting around the Sun explained the observable variations of Mars and Venus. In addition, he suggested that relatively small changes in the angle of Earth's axis over time explained the precession of the equinoxes, that is, the gradual shifting of the constellations in the night sky over time. The then-observable planets were in the following order from the Sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. All of these radical ideas were presented in Copernicus' De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), a work of six volumes, not published until 1543.

As it happened, reaction to Copernicus' theory was rather tame all around, and even the small pool of astronomers who were its intended audience measured barely a ripple of reaction. Ptolemaic astronomy was still the orthodox view of the cosmos. Eventually, later scientists began to explore the same themes and seek ever more accurate astronomical tables. As Copernicus' ideas took a tighter grip on the minds of European intellectuals, the reformist Martin Luther (1483-1546) denounced De Revolutionibus. By 1616, Copernicus' work was so widely known it was seen as a serious threat and condemned as heretical by church authorities, who listed it as a forbidden book.

Another giant leap forward in astronomy was made by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564-1642). He created his own super-powerful telescope, and with it, he could see what no human eye had ever seen before. Galileo began to build bold new theories based on his startling observations. Perhaps Galileo's most significant observations in relation to our story of Ptolemy were on the phases of Venus, which showed that it revolved around the Sun, and on the movement of the sunspots of the Sun, which suggested that it was a revolving sphere. In short, Galileo showed that Copernicus was right and the Ptolemaic Earth-centred system was wrong. Galileo was tried and found guilty of heresy by the Catholic Church in 1633, but this did not stop other thinkers also rejecting the old Ptolemaic model of the universe, for "no competent astronomer defended the traditional Ptolemaic system once they had heard that Venus had a full set of phases; you had to be an ill-informed philosopher to do so" (Wootton, 226). In short, "it was the telescope that killed off the Ptolemaic system" (Wootton, 246).

Scientists, armed with precision instruments, had taken over from natural philosophers in how best to explain the world around us. The German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) continued the work of Copernicus and Galileo, and he discovered that the heavenly bodies move in elliptical and not perfectly circular orbits around the Sun. Suddenly, our galaxy – and by now astronomers had a pretty good idea that what we could see is only a small part of the universe -– had become a comprehensible example of the laws of physics. Ptolemy's model of the universe was now as useless as his world map, as the landscape of knowledge was completely transformed by the Scientific Revolution.