Cleopatra of Macedon (355/4-308 BCE), daughter of Philip II of Macedon (reign 359-336 BCE) and his Molossian queen, Olympias of Epirus (c. 375-316 BCE), was the only full sister of Alexander the Great (reign 336-323 BCE). Born in Pella, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia, Cleopatra grew up as a royal princess in the Argead court. She later became the queen of Epirus through her marriage to her maternal uncle, Alexander I of Epirus (reign 343/2-331 BCE). Their son, Neoptolemus II (reign 302 to 297 or 295 BCE), was very young when his father left for a military expedition in Italy. In his absence, Cleopatra reigned as a regent almost independently for a few years.

Despite this prestigious background, Cleopatra's life is poorly documented, and what is known about her is limited and often controversial. Unlike her mother and older half-sister, Cynane (c. 357-323 BCE), who are portrayed with more distinctive and assertive images in ancient records, Cleopatra's significance is overall associated with her role in the political strategies of her male, and sometimes even female, peers. Ironically, she spent the rest of her relatively long life as an independent woman, namely without any appointed kyrios (male guardian), while trying to find a suitable husband. Although courted by many significant leaders of her time, Cleopatra's several plans for marriage failed, and she ultimately lost her life over her final attempt.

Early Life & Marriage

Like her father, Philip II, and brother Alexander, Cleopatra was born in Pella, the new capital of the kingdom of Macedonia established by her great-great-grandfather, Archelaus of Macedon (reign 413-399 BCE). The city of Pella, meaning ‘stone' or 'rock', was constructed at the beginning of the 4th century BCE about one kilometre east of its modern successor to replace the old capital, Aigai. Cleopatra's date of birth, 355/4 BCE, is essentially estimated in relation to Alexander's in 356 BCE, and sometimes causes confusion since Cleopatra Eurydice, Philip II's seventh and last wife, is also believed to share Cleopatra's birth date. The name Cleopatra, meaning ‘honour to her father', might have been selected after Archelaus' prominent wife, allegedly the first Cleopatra of Macedon (as stated by Aristotle in his Politics). According to extant inscriptions, the popularity of this name in the Greek world dawned at her time, around the 4th century BCE.

Cleopatra's early years in Pella are still obscure to us, but many scholars believe that young girls in the Macedonian court were liable to receive a relatively high level of education. This arrangement most likely stems from the fact that Macedonian kings were often away on military campaigns, and so royal women were left responsible for managing religious, administrative, and political matters within the court during their husbands' absences or acting as regents for their underage male heirs. In this context, it is likely that Cleopatra received at least some of the education provided to her brother, Alexander, and his companions in Pella.

When Cleopatra turned 18, she was given in marriage to her mother's brother, Alexander I of Epirus. He was the son and heir of Neoptolemus I (reign 370-357 BCE), who had been jointly ruling Epirus with his brother, Arybbas (reign 370-343 BCE). Alexander I was only a child when his father died, and his uncle became the sole ruler. To protect the young prince from potential threats, Philip II brought him to Pella, where he was raised alongside his own nephew and niece, Alexander and Cleopatra.

Around 343 BCE, when Alexander I was in his early twenties, Philip II deposed Arybbas and returned the throne of Epirus to him. In 337 BCE, Olympias left the Macedonian court to take refuge with him in Epirus. She was offended by Attalus, the guardian and uncle of Philip II's new bride, Cleopatra Eurydice, who had disrespected Olympias at the wedding without facing any confrontation from Philip. While there, Olympias tried to persuade her brother to oppose her husband, but Alexander I refused and instead agreed to reaffirm his alliance with Philip II by marrying Cleopatra.

The wedding, as testified by almost every writer past and present, was extremely lavish, partly as an apologetic welcome back to Olympias, but most likely as "an international panēguris [general gathering] with public processions, sacrifices, and theatrical performances" to promote the power and prominence of Macedonia (Carney, Philip II, 47). During these celebrations in October 336 BCE, Philip II was assassinated when coming out of the theatre in Aigai. His assassin, Pausanias of Orestis, who served as one of his bodyguards, was immediately killed by another bodyguard, Leonnatus (356-322 BCE), a friend and companion of Alexander from the royal house of Lynkestis, hence a relative of Philip's mother, Eurydice I (reign 393-369 BCE).

Queen of Epirus

After the wedding, hastily followed by Philip II's funeral and Alexander's coronation, Cleopatra moved to Epirus with her husband. Their children, Neoptolemus II and his sister Cadmeia, were most likely born soon after, since their father, Alexander I, left for a campaign in Italy in 334 BCE and never returned.

Following her husband's departure, Cleopatra became the regent to their infant son. Although she was generally ignored by historians, ancient sources that pay attention to Cleopatra sometimes depict her as a theatadoch (head of religious affairs), but more often focus on her close relationship and constant correspondence with Alexander the Great. According to Memnon (FGrH 434, F 4.37), Cleopatra not only enjoyed her association with Alexander the Great but also wielded sufficient influence over him to receive requests for exploiting this connection.

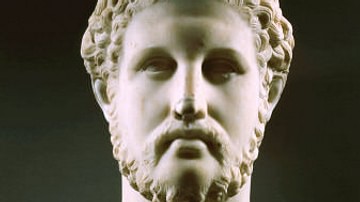

![Alexander the Great [Profile View]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/1047.jpg?v=1750706345)

Archaeological evidence, on the other hand, has recently begun to reveal a deeper view of Cleopatra at the office. An honorary inscription from Epirus, SEG XXIII 189, lists her as the only female chief official welcoming religious delegates to Epirus, which had a prestigious position as the state presiding over the oracle of Zeus at Dodona. Pausanias (1.44.6) implies that Cleopatra of Macedon had the means and authority to commission a special tomb for Telephanes, a celebrated Samian flute-player who was her contemporary.

However, it is much more common for historical records to remain silent about Cleopatra and other female rulers altogether. Although this omission may be attributed to the prevalent attitude of the time, it may also indicate that women's authority, irrespective of any personal or situational concessions, was primarily confined to domestic administration and public religious roles. Cleopatra and her mother, Olympias, were both independently mentioned in a recently found inscription from Cyrene as the recipients of grains in the late 330s BCE. Such archaeological evidence can provide information about female characters in history that were ignored or dramatically reshaped by ancient writers. Plutarch particularly put his emphasis on Cleopatra's and Olympias' unconventional pursuit of political power and their departure from the moral values expected of respectable women. He cites a letter from Alexander that describes Cleopatra's affair with a young courtier, although in this citation, Alexander says carelessly that his busy sister certainly deserves a pleasing break from her responsibilities (Plutarch, Moralia 818b-c).

In 331 BCE, Cleopatra's husband was killed in the Battle of Pandosia against the local Lucanians and Bruttians in southern Italy. According to Aeschines, Cleopatra received the Athenian envoys delivering the consolation message as an independent widow queen (Against Ctesiphon 242). However, we have no further evidence of Cleopatra's reign in this position. Historical writings agree that Alexander I was succeeded by his cousin Aeacides (reign 331-316 BCE), son of Arybbas. Cleopatra must have returned to Macedonia with her children shortly after. Interestingly, around the same time, Olympias moved to Epirus after years of attempting to overpower Antipater (reign 321-319 BCE), who was governing Macedonia as regent during Alexander the Great's absence. However, it is unlikely that she could remain in a court no longer governed by her brother, her daughter, or her very young grandson.

Again, Plutarch remains our only source regarding the supposed plans of Olympias and Cleopatra for ruling Epirus and Macedonia, respectively. He reports that Alexander praised his mother's choice but expressed doubts about the Macedonians ever accepting the rule of a woman:

For even against Antipater, Olympias and Cleopatra had raised a faction, Olympias taking Epirus, and Cleopatra Macedonia. When he heard of this, Alexander said that his mother had made the better choice; for the Macedonians would not submit to be reigned over by a woman.

(Plutarch, Alexander 7.68.4-5)

Royal Widow

Alexander never showed much interest in acting as a kyrios for his widowed mother or sisters. After one failed attempt to marry off his recently widowed half-sister, Cynane, in his early days on the throne, there is no evidence that Alexander ever again stepped forward as a male guardian to a female next of kin. On the other hand, there were several Macedonian widowed queens who decided to remarry or remain single without the involvement of a kyrios. Therefore, it is highly probable that Cleopatra spent the years between 331 BCE and the death of Alexander the Great quietly, focusing on raising her children and managing domestic and possibly religious responsibilities.

Alexander's sudden death in 323 BCE changed everything once and for all. During the next four decades between 323 and 281 BCE, Alexander's commanders, relatives, governors, and regents bitterly fought each other over a lion-share, or even all, of his newly conquered empire in a series of conflicts known as the Wars of the Diadochi (= Crown Princes, namely Alexander's Successors). A key aspect of this power struggle involved legitimizing one's claim of succession by marrying one of the royal Macedonian widows, who were Philip II's daughters and Alexander's sisters. When Cynane was killed in battle in 322 BCE, the available marriage options were reduced to Cleopatra and Thessalonike (c. 345-295 BCE).

For reasons still disputed, Thessalonike seems to have remained unmarried until her late 20s. She is nearly lost to historians before her marriage to Cassander (reign 317-297 BCE), one of the Diadochi, who defeated and killed Olympias in 316 BCE and went on to eliminate Alexander's only legitimate son and heir, Alexander IV of Macedon (323-309 BCE), as well as his mother, Roxanne. On the other hand, Cleopatra soon became a precious pawn to everybody's ambitious plans and eventually received proposals from almost all of the Diadochi, including Cassander, Lysimachus, Antigonus I, and Ptolemy I.

Suitors & Death

Cleopatra's first marriage plan, however, was reportedly set by her or her mother. Shortly after Alexander's death, Cleopatra wrote a letter to Leonnatus of Lynkestis, her childhood companion and Alexander's close friend, and invited him to come and marry her. Leonnatus at that time was the governor of Phrygia on the Hellespont, appointed by Alexander's trusted commander, Perdiccas (c. 355-320 BCE). Apparently, Cleopatra's offer pleased Leonnatus, who immediately set out for Macedonia. Before getting there, however, for reasons still disputed by scholars, Leonnatus took an army with him to suppress the Athenians' revolt against the Macedonian hegemony following Alexander's death. His campaign earned a decisive victory for the Macedonians, although it ultimately cost him his life (Plutarch, Phocion 25.5).

Following Leonnatus' death in the spring of 322 BCE, Cleopatra shifted her marital plans to target an even better option, Perdiccas. Having received Alexander's signet seal from the king himself, Perdiccas was presiding over the new empire on behalf of Alexander's brother and immediate successor, the mentally disabled King Philip III Arrhidaeus of Macedon (reign 323-317 BCE), who was incapable and not expected to live long. A marriage between Perdiccas and Cleopatra could potentially put an end to further conflicts over Alexander's succession, with his chosen commander and sister on the throne of the Macedonian Empire. However, Cleopatra and Olympias were not the only parties that crucially needed an association with Perdiccas. Their toughest enemy, Antipater, had similar intentions. As Alexander's regent during his absence, Antipater had ruled in the Argead court at Pella and would do anything to secure his seat. When Cleopatra went to Sardis to join Perdiccas in response to her marriage offer, she discovered that Perdiccas was already engaged to Antipater's daughter, Nicaea (c. 335 to c. 302 BCE).

Although Perdiccas went on and married Nicaea, he soon accepted the advice of Eumenes of Cardia (c. 361-315 BCE), Alexander's personal secretary, and divorced her to marry Cleopatra. This not only enraged Antipater but alerted the rest of the Diadochi about Perdiccas' ultimate win of Alexander's throne. Neither of them hesitated to attack Perdiccas at once, and thus the First War of the Diadochi started before the end of 322 BCE. Perdiccas, a highly skilled commander, achieved considerable success even though he had to confront numerous enemies with only a few allies. However, his progress against Ptolemy's forces in Egypt turned out to be so slow and exhaustive that he was eventually assassinated by his own dissatisfied generals in 320 BCE.

With Perdiccas out of the way, the other Diadochi wasted no time trying to take his place beside Cleopatra. A prominent figure among them was the cunning Eumenes, who made known his plans for fighting and defeating Antipater only to win Cleopatra's favour. Cleopatra, however, had no illusions about Antipater's massive power and Eumenes' lack of military means and prowess. Therefore, she talked Eumenes out of his plans and convinced him to leave safely and in peace.

Although Cleopatra's attempts at marriage were unsuccessful, Antipater grew increasingly concerned about her influence over ambitious successors. He initially sought to undermine her by accusing her, perhaps publicly, of being capricious in her philia (friendliness) with Perdiccas and Eumenes. However, these accusations were easily dismissed. Cleopatra, in return, took a more direct approach by reminding Antipater of how he had supported Perdiccas in killing her sister, Cynane. This forced Antipater to reconsider his position, and he began to contemplate either marrying Cleopatra or arranging for one of his sons to marry her.

Before any of this could take place, however, Antipater died in 319 BCE, and the Second War of the Diadochi broke out over filling his place of rulership over Macedonia. The course of the conflicts went in a way that gave immense power to one of the most prominent commanders in Alexander's army, Antigonus I Monophtalmos (The One-Eyed, 382-301 BCE). He managed to take over quite a few key centres of Alexander's empire, including Sardis. From then on, Cleopatra lived under his protection, or rather, as understood by most scholars, "a virtual house detention" (Whitehorne, 58). Nothing much is known about her life for a decade, although it could not have been without fear, grief, and sorrow with the murder of her mother, Olympias, in 316 BCE and of her teenage nephew, Alexander IV, in 310 BCE, amongst the ceaseless twists of her own fate during the Wars of Succession.

In 308 BCE, Ptolemy, already the ruler of Egypt, in his expeditions against Antigonus, landed in Asia. Cleopatra, agitated by a recent quarrel with Antigonus and/or exhausted from living in his confinement, left Sardis to join him. She was arrested halfway, returned to Sardis, and secretly murdered by one of her female attendants. As Diodorus tells us:

The governor of Sardis, who had orders from Antigonus to watch Cleopatra, prevented her departure; but later, as commanded by the prince, he treacherously brought about her death through the agency of certain women. But Antigonus, not wishing the murder to be laid at his door, punished some of the women for having plotted against her, and took care that the funeral should be conducted in royal fashion. Thus Cleopatra, after having been the prize in a contest among the most eminent leaders, met this fate before her marriage was brought to pass.

(20.37.5-6)

With Cleopatra's death, little was left to complete the history of the Argeads. Her son, Neoptolemus II, took the throne of Epirus and ruled for a few years until 297 BCE, when he was murdered and replaced by his cousin, Pyrrhus (reign 297-272 BCE). Two years later, Cleopatra's youngest sister, Thessalonike of Macedon, was also murdered by her own son in 295 BCE, who then went on and killed his brother and was murdered in a matter of months.