Colonel Tye (c. 1753-1780) was an African-American Loyalist leader who commanded one of the most effective guerilla forces of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Born into slavery, he escaped in 1775 and joined the British cause, leading a Loyalist militia known as the Black Brigade on raids against Patriot militias. He died in September 1780 of wounds sustained during a raid.

Early Life & Escape from Slavery

The man who would become Colonel Tye was born into slavery as Titus, on a farm in Monmouth County, New Jersey, c. 1753. Titus was one of four male slaves owned by John Corlies, a farmer whose land was nestled along the Navesink River, near the town of Shrewsbury. Corlies was, at least ostensibly, a Quaker, although he did not seem to possess many of the qualities valued by the Society of Friends. He did not share the Quaker belief in pacifism and was frequently reprimanded by others in the movement for drinking, cursing, and brawling. More concerning, however, was Corlies' reputation as a cruel slaveowner. He was known to beat Titus and his other slaves for the slightest of infractions, which disturbed many of his fellow Quakers, who found the practice of slavery to be abhorrent.

Indeed, in 1758, the Quakers of New Jersey and Pennsylvania passed an edict with the intention of gradually abolishing slavery within their own ranks. Quaker slaveowners were expected to voluntarily emancipate their slaves upon the slave's 21st birthday (considered the age of adulthood in 18th-century America). Slaves under the age of 21 were to be provided with education in the Quaker ideology and were to be taught how to read and write so that they could be as self-sufficient as possible upon their release. Corlies proved neglectful in these duties; he did not provide his slaves with education and failed to emancipate Titus upon his 21st birthday around 1774. In the autumn of 1775, Corlies was visited by a delegation of New Jersey Quakers, who urged the wayward slaveowner to educate and free his slaves or risk expulsion from the Quaker movement. Corlies, a quick-tempered man, was only angered by the ultimatum and doubled down on his behavior; the Quakers left the Corlies farm after having been told that Corlies "has not seen it his duty to give [the slaves] their freedom" (Hodges, 91).

Titus had undoubtedly observed the visit of the Quaker delegation and was aware as to why they had come. He also would have known that most other 21-year-old slaves with Quaker masters had already been freed, a fact that would have further hardened his heart against his own harsh master. By this point, the excited fervor that underscored the American Revolution (1765-1789) had seeped its way into Monmouth County; as New Jersey Patriots loudly pontificated about American liberty and freedom from the slavery of Great Britain, the people who were actually enslaved in the county wondered what all this meant for them. At night, groups of Monmouth County slaves would sneak off their masters' properties and hold meetings, where they discussed if their own personal freedoms might fit within the broader Patriot movement; as if in answer, the town of Shrewsbury authorized the arrests of all "slaves, Mulattos, and Negroes found off their masters' premises" after dark (Hodges, 94).

It was around this time, November 1775, that Titus made his escape from his master's farm. Shortly thereafter, John Corlies put out an advertisement offering a reward for the return of Titus, who Corlies described as being:

About 21 years of age, not very black, near six foot high, had on a gray homespun coat, brown breeches, blue and white stockings and took with him a wallet drawn up at one end with a string in which was a quantity of clothes (Hodges, 92).

So, with only a bag full of clothes to his name, Titus evaded the slave catchers and moved south toward Norfolk, Virginia. There, he expected to find his freedom; but it was the British, not the liberty-loving Patriots, who he expected would give it to him.

Dunmore's Proclamation

During the American Revolutionary War, thousands of African Americans, both enslaved and free, would fight for the Patriot cause. While many of them served because they were forced to by their masters or just because they yearned for a life off the land on which they were enslaved, many others fought because they genuinely believed that they were helping to forge a nation that would set them free; a lie that other enslaved men, like Titus, could see straight through. Indeed, in July 1775, General George Washington, commander-in-chief of the American forces, issued a decree that forbade Black soldiers from serving in the Continental Army. Like many other wealthy slaveowners, Washington dreaded the ever-present possibility of a slave revolt and feared the consequences of arming and training enslaved men. This decree was eventually retracted, as the Patriots soon realized they needed Black soldiers to supplement their army, and these Black soldiers were even promised freedom as a reward for their military service. However, the initial sentiment of Washington's decree betrayed the fact that the abolition of American slaves was nowhere near the top of many Patriots' priorities.

Therefore, it is not difficult to understand why Titus – and many other enslaved African Americans – chose to side with the Tories (or Loyalists) rather than the Patriots. Slavery in Colonial America was a common practice; out of the 2.5 million people who lived in the Thirteen Colonies, 450,000 were enslaved. In England, slavery had never been officially legalized and was often looked upon as an outdated practice. In the 1772 landmark case Somerset v. Stewart, the English courts ruled that slavery did not exist under English common law and that slaveowners could not legally send their slaves outside of England against their will. The case was closely followed in the colonies, with many (falsely) interpreting it to mean that slavery was completely abolished in England. The English courts were petitioned for the abolition of slaves who resided in England, while many American runaway slaves stowed away on ships, hoping to reach English shores where they believed they would be free.

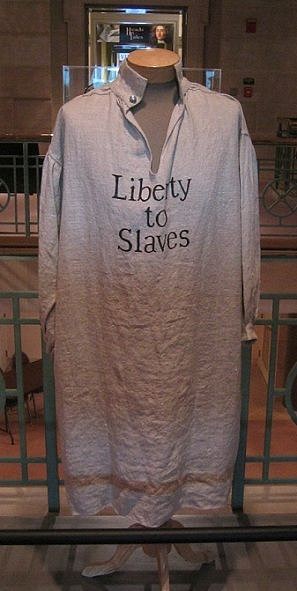

In November 1775, around the time that Titus was making his escape, the British looked to capitalize on the Patriots' fear of slave revolts. Lord Dunmore, the royalist governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to any enslaved man willing to take up arms against the Patriots and help end the American rebellion. Within a month of the proclamation, over 800 slaves had arrived in Norfolk to enlist in Loyalist militias, with thousands more on their way. Many of these men were organized into Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment, an all-Black military unit, issued uniforms imprinted with the words 'Liberty to Slaves'. The proclamation had its desired effect; Virginian slaveowners panicked, threatening to execute any slave who sided with the Loyalists, but many of those slaves, such as Titus, were willing to risk that outcome for a chance at freedom. Upon arriving at Norfolk sometime in December 1775, Titus enlisted in Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment. On the muster roll, he was listed as 'Tye', the name he would henceforth be known as.

The Black Brigade

Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment saw action in late 1775 and early 1776, mostly in skirmishes against Virginian Patriot militias. During this time, the Ethiopian Regiment was plagued by smallpox, which killed a large percentage of its troops. In the summer of 1776, the regiment was sent to Staten Island to partake in the planned British attack on New York City. However, General William Howe, commander of the British forces, was confident that his army of 32,000 men was already sufficient; believing he had no need for the Ethiopian Regiment, Howe disbanded the unit. The British would go on to defeat Washington's army at the Battle of Long Island (27 August 1776) and capture New York City, which would become the base of British operations in the north. Even though General Howe did not need Black troops, the British still found it viable to free American slaves as a form of economic warfare against the Patriots. In 1779, British general Sir Henry Clinton issued the Philipsburg Proclamation, which took the Dunmore Proclamation a step further and offered freedom to any slave who escaped from their Patriot master and made it safely to British-occupied territories. As a result, hundreds of escaped slaves began flocking to New York City.

During this time, Tye's whereabouts are uncertain. He does not appear in the historical record again until the Battle of Monmouth Court House (28 June 1778), by which time he was once again serving with the British. Tye distinguished himself during the battle and even captured a Patriot militia captain. His service caught the attention of William Franklin, a Loyalist leader and former royal governor of New Jersey (as well as the son of renowned Patriot leader Benjamin Franklin). Governor Franklin had a problem; New Jersey Tories were being rounded up and summarily executed by New Jersey Patriot militias under a new vigilante law that allowed for such extra-judicial violence. As a form of retaliation, Franklin outfitted and supplied several Loyalist militias to launch raids against New Jersey Patriots. One of these militias was a 24-man all-Black unit called the Black Brigade. It was commanded by Tye, who was by now being referred to as 'Colonel'; this was not an official rank, but rather a show of respect from the British, who had come to be awed by Tye's martial abilities.

Colonel Tye led his first raid on 15 July 1779, when he and 50 Black and White Tories landed at Shrewsbury and raided nearby farms. They plundered 80 heads of cattle, 20 horses, a large amount of clothing and furniture, and captured two Shrewsbury residents, Brindley and Elisha Cook. Before the Patriot militias could be alerted, Tye had already slipped down the river and retreated to his headquarters of Refugeetown on Sandy Hook, one of the last British bastions in Patriot-controlled New Jersey. Colonel Tye led several more raids during the autumn of 1779. Having spent most of his life in Monmouth County, his intimate knowledge of the land allowed him to travel swiftly through the swamps, rivers, and inlets. Tye often targeted Patriot slaveowners and their friends, surprising them in their homes and carrying off large quantities of Patriot silver, clothing, and cattle. Tye and his men were paid as much as five gold guineas by British officials for each successful raid. One author characterized Tye's raids as "banditry, reprisal, and commissioned assistance to the British army" (Hodges, 98).

During the bitter winter of 1779-80, the British and Tories inside New York City were running low on food and firewood. With the British grasp on New York as tenuous as it had ever been, Colonel Tye's Black Brigade joined with another Loyalist militia known as the Queen's Rangers to defend the city and scour the surrounding countryside for food and fuel. This greatly supported the British garrison of New York and contributed to the Tories maintaining control of the city. In the spring of 1780, Colonel Tye resumed his raids; on 30 March, he captured three Patriot militia officers. That same month, he led a raid on the home of John Russell, a Patriot associated with recent attacks against Tories on Staten Island. Russell was killed in the ensuing struggle, and his son was wounded.

Raids of June 1780

Perhaps the most productive period of Colonel Tye's career occurred over the course of a single week in June 1780, when he conducted three separate raids on the 8th, 9th, and 12th. During the second of these raids, Tye led an attack on the home of Joseph Murray, a private in the Monmouth County militia who had been personally responsible for the summary executions of several Tories. In retribution for those murders, Murray was killed by Tye. On the night of 12 June, during his third raid, Tye led a large band consisting of both Black and White Loyalists in an attack on the home of Barnes Smock, a high-ranking officer in the Monmouth County militia. Smock noticed the large numbers of armed Tories sneaking up on his house in the night and fired a six-pound cannon, alerting his neighbors that he was in danger.

This resulted in a skirmish, as several Monmouth militiamen raced to defend Smock's property, but they were no match for Tye and his Black Brigade, which were now quite experienced. After a brief firefight, Smock and twelve Patriot militiamen became Tye's prisoners. The Tories then captured Smock's livestock and looted his home before quickly slipping back to Sandy Hook with their loot and prisoners. In a single week, Tye had captured most of the leadership of the Monmouth County militia and had destroyed its cannons. Before the June raids, Tye had been written off by the Patriot leadership of New Jersey as a simple bandit; now, he was recognized as a military force to be reckoned with. He appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette as Colonel 'Ty', where he was described as a Loyalist leader "who wears the title of colonel and commands a motley crew at Sandy Hook" (American Battlefield Trust). Residents of Monmouth County pleaded with New Jersey's Patriot governor, William Livingston, for protection against the Black Brigade. In response, Governor Livingston declared martial law and ordered the remaining members of the Monmouth County militia to hunt Tye down. However, the militiamen had become so afraid of Tye and the Black Brigade that only two of the 17 members mustered for service.

On 22 June 1780, Colonel Tye added another chapter to his fast-growing legend. Leading a large party consisting of 30 troops from the Black Brigade, 36 Queen's Rangers, and 30 other Loyalists, he landed at Conascung, New Jersey. Utilizing his knowledge of the land, Tye slipped past the Patriot troops that were searching for him to attack the home of Major James Mott, a leader of Monmouth County's second militia regiment. Mott was taken prisoner, and his house was burned to the ground along with the homes of several of Mott's Patriot neighbors. That same day, Colonel Tye attacked the Hunterdon militia, taking seven of them prisoner before escaping back to his headquarters on Sandy Hook. In a single day, he had taken eight prisoners, secured lots of valuable loot, and had returned to safety, without losing a single man. But just as Tye had reached the peak of his fearsome reputation, his luck was about to run out.

Final Raid & Death

After laying low for most of the summer of 1780, Colonel Tye decided to make his grand return with a move against Josiah Huddy, a prominent New Jersey Patriot who had led attacks against the British on Staten Island and who had personally executed several captured Tories without trial. On the night of 1 September 1780, Tye led a party of Black and White Loyalists in a surprise attack on Huddy's home. Huddy, who was spending the evening with a lady friend named Lucretia Emmons, noticed the advancing Tories and rushed to defend his home. Huddy ran from room to room, firing muskets at the approaching Tories and handing his guns to Emmons, who would quickly reload. Huddy kept up such consistent fire that the frustrated Colonel Tye had to set fire to Huddy's home to flush the Patriot out. This plan worked, as Huddy agreed to surrender on the condition that the Tories extinguish the flames.

After Huddy's surrender, the Tories raided his home for loot before returning to the Shrewsbury River, intending to take their prisoner back to Sandy Hook. But as they were loading Huddy into a boat, shots rang out from the opposite riverbank. Patriot militiamen had been alerted by the sound of musket fire, and, having realized that Huddy must be under attack, had rushed to defend him. During the confused skirmish that followed, Huddy jumped into the river and was able to swim to safety, after which the Patriot militiamen withdrew. Although none of the Tories had been killed, Colonel Tye had been shot in the wrist. Initially, the wound appeared to be minor, leading Tye to forego seeking medical attention, but a few days later the wound became infected with tetanus, and lockjaw set in. Colonel Tye died of this wound in early September 1780, aged only 27. His career had lasted for only a year, yet in that time, he had become the most feared and respected Loyalist guerilla fighter of the entire conflict.

After Tye's death, a Black Loyalist named Stephen Bucke took command of the Black Brigade. But since Bucke lacked Tye's intimate knowledge of Monmouth County, the brigade was much less effective. In October 1781, the surrender of Lord Charles Cornwallis' British army at the Siege of Yorktown meant that a Patriot victory in the war was all but assured; the Black Brigade continued to hold out until the bitter end, however, conducting minor raids in New Jersey. It scored one final victory in mid-1783 when it captured and hanged Josiah Huddy in retribution for the death of Colonel Tye. When the last British troops evacuated from the United States in November 1783, after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Bucke and the surviving members of the Black Brigade went with them, settling in Canada. While the Patriots considered most White Tories to be traitors, they nevertheless held Colonel Tye and his Black Brigade with great esteem; indeed, these men, fighting to secure their freedoms, proved some of the most effective raiders of the Revolutionary War.