The Colosseum or Flavian Amphitheatre is a large ellipsoid arena built in the first century CE by the Flavian Roman emperors of Vespasian (69-79 CE), Titus (79-81 CE) and Domitian (81-96 CE). The massive arena held 50,000 spectators and hosted spectacular public entertainments such as gladiator fights, wild animal hunts, and public executions from 80 CE to 404 CE.

Purpose & Dimensions

The construction of the Colosseum was begun in 72 CE in the reign of Vespasian on the site that was once the lake and gardens of Emperor Nero's Golden House. This was drained and as a precaution against potential earthquake damage concrete foundations six metres deep were put down. The building was part of a wider construction programme begun by Emperor Vespasian in order to restore Rome to its former glory prior to the turmoil of the recent civil war. As Vespasian claimed on his coins with the inscription Roma resurgens, the new buildings —the Temple of Peace, Sanctuary of Claudius and the Colosseum— would show the world that 'resurgent' Rome was still very much the centre of the ancient world.

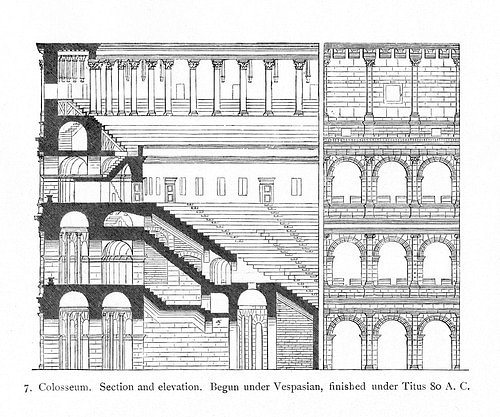

The Flavian Amphitheatre (or Amphiteatrum Flavium as it was known to the Romans) opened for business in 80 CE in the reign of Titus, Vespasian's eldest son, with a one hundred day gladiator spectacular and was finally completed in the reign of the other son, Domitian. The finished building was like nothing seen before and situated between the wide valley joining the Esquiline, Palatine and Caelian hills, it dominated the city. The biggest building of its kind, it had the following features:

- four stories.

- a height of 45 metres high (150 feet).

- a width of 189 x 156 metres.

- an oval arena measuring 87.5 m by 54.8 m.

- a roofed awning of canvas.

- capacity for 50,000 spectators.

The theatre was principally built from locally quarried limestone with internal linking lateral walls of brick, concrete and volcanic stone (tufa). Vaults were built of lighter pumice stone. The sheer size of the theatre was the possible origin of the popular name of Colosseo, however, a more likely origin may have been as a reference to the colossal gilded bronze statue of Nero which was converted to resemble the sun-god and which stood outside the theatre until the 4th century CE.

Architecture

The theatre was spectacular even from the outside with monumental open arcades on each of the first three floors presenting statue-filled arches. The first floor carried Doric columns, the second Ionic and the third level Corinthian. The top floor had Corinthian pilasters and small rectangular windows. There were no less than eighty entrances, seventy-six of these were numbered and tickets were sold for each. Two entrances were used for the gladiators, one of which was known as the Porta Libitina (the Roman goddess of death) and was the door through which the dead were removed from the arena. The other door was the Porta Sanivivaria through which victors and those allowed to survive the contests left the arena. The final two doors were reserved exclusively for the Emperor's use.

Inside, the theatre must have been even more impressive when the three tiers of seats were filled with all sections of the populace. Encircling the arena was a wide marble terrace (podium) protected by a wall within which were the prestigious ring-side seats or boxes from where the Emperor and other dignitaries would watch the events. Beyond this area, marble seats were divided into zones: those for richer private citizens, middle-class citizens, slaves and foreigners and finally wooden seats and standing room in the flat-roofed colonnade on the top tier reserved for women and the poor. On top of this roof platform sailors were employed to manage the large awning (velarium) which protected the spectators from rain or provided shade on hot days. The different levels of seats were accessed via broad staircases with each landing and seat being numbered. The total capacity for the Colosseum was approximately 45,000 seated and 5,000 standing spectators. One of the oldest depictions of the Colosseum appeared on the coins of Titus and shows three tiers, statues in the upper external arches and the large column fountain - the Meta Sudans - which stood nearby.

The scene of all the action —the sanded arena floor— was also eye-catching. It was often landscaped with rocks and trees to resemble exotic locations during the staging of wild animal hunts (venatiories). There were also ingenious underground lifting mechanisms which allowed for the sudden introduction of wild animals into the proceedings. On some occasions, notably the opening series of shows, the arena was flooded in order to host mock naval battles. Under the arena floor (and visible to the modern visitor) was a maze of small compartment rooms, corridors and animal pens.

Games & Shows

Although historically tied to earlier Etruscan games which emphasised the rites of death, the shows in the Roman arenas were designed simply to entertain, however, they also demonstrated the wealth and generosity of the Emperor and provided an opportunity for ordinary people to actually see their ruler in person. Emperors were usually present, even when they had no particular taste for the events such as Marcus Aurelius. Titus and Claudius were noted for shouting at the gladiators and other members of the crowd and Commodus himself performed in the arena hundreds of times. One vestige of the earlier Etruscan tradition continued, however, with the presence of the attendant whose job was to finish off any fallen gladiator by a blow to the forehead. This attendant wore the mythical costume of either Charon (the Etruscan minister of Fate) or Hermes, the messenger god who accompanied the dead down to the underworld. The presence of the Vestal Virgins, the Pontifex Maximus and the divine Emperor also added a certain pseudo-religious element to the proceedings, at least in Rome.

However, blood sports and death were the real purpose of the spectacular shows and an entire profession arose to meet the massive entertainment requirements of the populace - for example under Claudius there were 93 games a year. Spectacles often lasted from dawn till nightfall and the gladiators usually kicked-off the show with a chariot procession accompanied by trumpets and even a hydraulic organ and then dismounted and circled the arena, each saluting the emperor with the famous line: Ave, imperator, morituri te salutant! (Hail, Emperor, those who are about to die salute you!).

Comic or fantasy duels often began the day's combat events, these were usually fought between women, dwarfs or the disabled using wooden weapons. The following blood sports between various classes of gladiators included weapons such as swords, lances, tridents, and nets and could also involve female combatants. Next came the animal hunts with the bestiarii — the professional beast killers. The animals had no chance in these contests and were most often killed at a distance using spears or arrows. There were dangerous animals such as lions, tigers, bears, elephants, leopards, hippopotamuses and bulls but there were also events with defenceless animals such as deer, ostriches, giraffes and even whales. Hundreds, sometimes even thousands of animals, were butchered in a single day's event and often brutality was deliberate in order to achieve crudeliter — the correct amount of cruelty.

Under Domitian, dramas were also held in the Colosseum but with a bloodthirsty realism such as using real condemned prisoners for executions, a real Hercules was burned on a funeral pyre and in the role of Laureolus a prisoner was actually crucified. The Colosseum was also the scene of many executions during the lunch-time lull (when the majority of spectators went for lunch), particularly the killing of Christian martyrs. Seen as an unacceptable challenge to the authority of Pagan Rome and the divinity of the Emperor, Christians were thrown to lions, shot down with arrows, roasted alive and killed in a myriad of cruelly inventive ways.

What Happened to the Colosseum?

In 404 CE, with the changing times and tastes, the games of the Colosseum were finally abolished by Emperor Honorius, although condemned criminals were still made to fight wild animals for a further century. The building itself would face a chequered future, although it fared better than many other imperial buildings during the decline of the Empire. Damaged by earthquake in 422 CE it was repaired by the emperors Theodosius II and Valentinian III. Repairs were also made in 467, 472 and 508 CE. The venue continued to be used for wrestling matches and animal hunts up to the 6th century CE but the building began to show signs of neglect and grass was left to grow in the arena. In the 12th century CE it became a fortress of the Frangipani and Annibaldi families. The great earthquake of 1231 CE caused the collapse of the southwest facade and the Colosseum became a vast source of building material - stones and columns were removed, iron clamps holding blocks together were stolen and statues were melted for lime. Indeed, Pope Alexander VI actually leased the Colosseum as a quarry. Despite this crumbling away though, the venue was still used for the occasional religious procession and play during the 15th century CE.

From the Renaissance period both artists and architects like Michelangelo and later tourists on their Grand Tour took a renewed interest in Roman architecture and ruins. As a consequence, in 1744 CE Pope Benedict XIV prohibited any further removal of masonry from the Colosseum and consecrated it in memory of the Christian martyrs who had lost their lives there. This, however, did not stop locals using it as an animal stables and its neglect is reflected in the curious work of Richard Deakin who in 1844 CE catalogued over 420 plant varieties thriving in the ruin, some rare and even locally unique — perhaps originating from the food given to the exotic animals all those centuries before. The 19th century CE did, though, begin to see the fortunes of the once great amphitheatre improve. The Papal authorities sought to restore parts of the building, notably the east and western ends, with the latter being supported by a massive buttress. Finally, in 1871 CE the Italian archaeologist Pietro Rosa removed all of the post-Roman additions to reveal, despite its degradation, a still magnificent monument, a poignant and enduring testimony to both the skills and the vices of the Roman world.