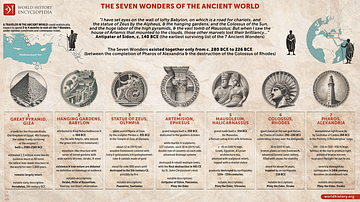

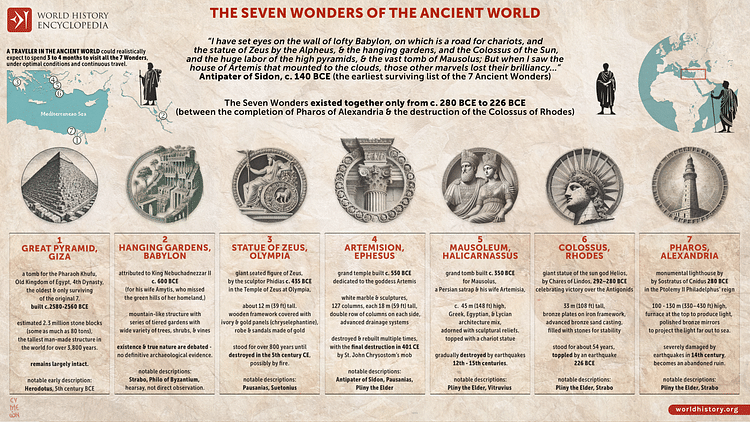

The Colossus of Rhodes was a gigantic 33-metre-high bronze statue of the sun god Helios which stood by the harbour of that city from c. 280 BCE. Rhodes was then one of the most important trading ports in the ancient Mediterranean and the statue was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Made by the local sculptor Chares using sheets of bronze, the statue soon appeared on contemporary travel writer's lists of must-see sights but sadly, the giant Helios did not last long. Toppled by an earthquake in 228 or 226 BCE, its massive broken pieces cluttered the docks of Rhodes for a millennium before being melted down as scrap in the mid-7th century CE.

Helios & Rhodes

Helios was the god of the Sun, offspring of the Titans Hyperion and Theia. Not specifically the subject of a widespread cult across Greece, Plato informs us in his Symposium and other works that many people, including Socrates, would greet the Sun and offer prayers each day. One place Helios was particularly worshipped was at Rhodes, the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece in the eastern Mediterranean. There he was the most important deity, their patron god, and honoured by the Halieia festival, the highlight of the island's religious calendar and a Pan-Hellenic games much like the ancient Olympic Games. Indeed, in the island's founding mythology, its very name derives from the nymph Rhodos, who bore seven sons to Helios. In the Hellenistic period (the 4th to 1st century BCE), Helios and the god Apollo would become practically synonymous.

The city of Rhodes, with its five harbours, was ideally placed on the island of the same name to prosper from trade during the Hellenistic domination of the Mediterranean under Alexander the Great's successors, especially when more and more cities were established in the East. The island's wealth and strategic position on trade routes did not go unnoticed by ambitious foreign rulers. Antigonus I (c. 382 - 301 BCE), one of Alexander's successors who controlled Macedon and northern Greece, was one such ruler, and he sent his son Demetrius I of Macedon (c. 336 - c. 282 BCE) to attack Rhodes in 305-4 BCE. The island's recent alliance with Antigonus' rival Ptolemy I (c. 366 - 282 BCE) in Egypt was another reason to attack Rhodes and neutralise its powerful naval fleet.

After a 12-month siege, the Rhodians and their formidable fortifications stood firm, and Demetrius negotiated a truce and abandoned the blockade. The Macedonian prince gained his nickname “the Besieger of Cities” but not much else. Demetrius left behind so much siege engine material, including one 36.5 metres (120 ft) high tower, that the Rhodians were able to sell it off for a handsome profit. The polis or city-state already had plenty of money from its lucrative control of trade and there seemed no better way to spend this new windfall than on a massive statue in honour of their patron god, a move which celebrated the island's hard-won freedom and which might perhaps perpetuate the good times the island was enjoying in the 4th century BCE.

The Colossus

The man commissioned with the Herculean task of sculpting the giant Helios was Chares of Lindus (a city on Rhodes). The project would not be finished until c. 280 BCE, and as the 1st-century CE Roman writer Pliny the Elder noted, it cost 300 talents and took at least 12 years to complete the bronze figure which stood some 70 cubits or 33 metres (108 ft) high. It is likely that the bronze outer shell, presumably applied in sheets and assembled on site, was supported by internal struts made of iron and certain pieces were weighted with stones to increase the figure's stability.

Although Helios was usually envisaged and represented in art as a charioteer with a sun-beamed halo riding across the sky and dragging the sun behind him, the Rhodians perhaps went for a more statuesque representation for their colossal figure. Unlike many other super-famous sculptures from antiquity, though, there are no surviving representations or scale models of the Colossus in other ancient art forms to help reconstruct in detail what the Colossus may have looked like. If the depictions of Helios on the Hellenistic silver coins of Rhodes are anything to go by, we can speculate that the statue may have had the god with his usual crown of pointed sunbeams. A relief of Helios on a stone from a temple at Rhodes has the god shading his eyes with one hand but whether this was replicating the stance of the Colossus or not is unknown. Similarly, the popular belief that the statue was holding a torch like the US Statue of Liberty is based on the misreading of a later Rhodian poem, thus confusing a real light with the metaphor of one in the statue's original base inscription.

The base of the statue carried the following inscription, preserved in the ancient anthology of poetry, the Palatine Anthology (VI.171):

To you, Helios, yes to you the people of Dorian Rhodes raised this colossus high up to the heaven, after they had calmed the bronze wave of war, and crowned their country with spoils won from the enemy. Not only over the sea but also on land they set up the bright light of unfettered freedom.

(quoted in Romer, 40)

The exact location of the statue is not known as no ancient writer bothered to say, but the eastern side of the harbour is the most likely spot. Certainly, later Roman statues at ports like Ostia had statues near their harbours which may have mimicked the great example at Rhodes. The medieval fortress of Saint Nicholas, itself built on the site of an earlier church dedicated to the same saint, still stands on the Mandraki harbour mole. Pagan monument sites were often reused by Christians as a potent symbol of the new order, and there was a tradition in medieval times that the broken feet of the Colossus once stood here. More concrete evidence, well, actually sandstone evidence, is a large circle of cut blocks which could have served as the foundation for the statue's base. In addition, there are fine, slightly curved marble blocks randomly used in the fortresses' walls which date to the 3rd century BCE, as well as odd-shaped stones which may have been part of the weights used in the statue's interior.

All that can be said for sure about the Colossus of Rhodes, then, is that it was massive and that quality was a particular feature of Hellenistic sculpture and art in general, as the historian P. Jordan here summarises:

The sun-god Colossus of Rhodes was pure Hellenism in its flashiness, its gigantism, its ambition, its advertisement of commercial success and even, though it was ostensibly a religious monument, in its aggrandisement of a particular human form. (33)

Like the Hellenistic Age itself, the statue's life was a brief one. Too big for its own good, the statue would, like the empire of Alexander, be shattered into pieces and picked over by subsequent cultures. If ever an art piece reflected a culture, it was the Colossus of Rhodes and its unfortunate fate.

The Seven Wonders

Some of the monuments of the ancient world so impressed visitors from far and wide with their beauty, artistic and architectural ambition, and sheer scale that their reputation grew as must-see (themata) sights for the ancient traveller and pilgrim. Seven such monuments became the original 'bucket list' when ancient writers such as Herodotus, Callimachus of Cyrene, Antipater of Sidon, and Philo of Byzantium compiled shortlists of the most wonderful sights of the ancient world. The Colossus of Rhodes made it onto the established list of Seven Wonders because of its audacious size. Previously, the Greeks had applied the term 'colossus' to statuary of any size, but from now on, thanks to the giant figure of Helios, the term would be applied only to very large figure sculptures.

The Colossus, along with many other structures on Rhodes, was toppled by an earthquake in either 228 or 226 BCE. According to the Greek geographer and writer Strabo (c. 64 BCE - 24 CE) in his Geography (14.2.5), the statue snapped at the knees and then lay forlorn and untouched because the locals believed the great oracle of Delphi's prediction that to move it would bring misfortune on the city. Pliny the Elder made the following observations on the Colossus' awesome aspect, even when in fragments:

This statue fifty-six years after it was erected, was thrown down by an earthquake; but even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior. Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of which the artist steadied it while erecting it. (Natural History, 34.18.41)

Around 654 CE, according to the Byzantine historian Theophanes (c. 758 - c. 817 CE), when Rhodes was occupied by the Muslims of the Umayyad Caliphate, a Jewish merchant from the city of Edessa in upper Mesopotamia bought the bronze wreckage of the Colossus to melt down and reuse the metal, transporting it to the East using 900 camels.