The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) was an independent, international organization, sponsored by neutral governments and with the guarantees and assurances of the belligerents to alleviate the suffering of German-occupied Belgium in the First World War (1914-1918). Headed by Herbert Hoover, the CRB, as an independent initiative, represented the first attempt in the modern period to address the problem of civilian relief during war.

German Occupation of Belgium

On the evening of 2 August 1914, the Belgian authorities were presented with an ultimatum by Germany requesting passage through Belgian territory to engage the French army. It declared that if Belgium observed a benevolent neutrality, making no opposition to the passing of German troops across its territory, its sovereign rights and independence would be guaranteed, and it would be compensated for all damage suffered. If they resisted, Belgium would be treated as an enemy. The Belgian government was given twelve hours to reply. There were no differences of opinion amongst the members of the Belgian cabinet; they refused Germany's request.

On 4 August, in violation of existing treaties, German armies swept across Belgium, and by the end of the month, most of Belgium was set apart as an occupied territory (Okkupationsgebiet) behind the zone of military operations. Field-Marshal Baron von der Goltz was appointed by the German emperor to be governor-general, and a central government was established under his command.

The destruction, requisitioning, and distribution of the country's existing food stocks created a desperate situation. The roads filled with refugees and threw the nation's economic life into disarray. The foremost problem confronting the country was the supply and distribution of staple necessities to the population. General services such as customs services, tax collection, and agricultural control and inspection remained intact under the strict supervision of the German authorities. The occupying Germans maintained the appearance that the Belgians were still administrating their own services. The post office and railways were taken over by the German administration and run as military institutions. Belgian law was retained but the German governor-general exercised the right to eliminate any existing laws or create new legislation.

There was also in force a complete code of military law and military tribunals for enforcement. Special departments administered every aspect of Belgian industry, commerce, and agriculture. German commissioners of banks supervised all financial operations. Central offices controlled the canals, railways, and coal mining industry. The means of travel were also limited. Automobiles were few, and the trams and railroads, when finally available for civilian use, were notoriously slow and restricted. Daily life was uncertain, and the people could never be sure from one week to the next what new restrictions or demands would be made upon the community. Nevertheless, the Belgian population maintained the hope that, within a relatively short period of time, the occupying Germans would be pushed back to their own borders.

Responsibility for Feeding Belgium

In 1914, about one-sixth of the Belgian population supported itself by agriculture, with total grain production equal to about one-fourth of that necessary for the consumption of the whole population. The country relied on the importation of nearly 80% of its cereals to maintain its food supply. Therefore, if anything happened that would shut Belgium off from the rest of the world, even for a short time, the country would begin to suffer. Great Britain's economic response to the initiation of hostilities was to impose a blockade around the Continent, with the intent of hampering Germany's overseas trade thereby limiting its military capabilities, but the blockade also prevented much-needed imports from reaching Belgium. Along with Germany's refusal to feed the civilian population of the country they now occupied raised the specter of famine by the winter. Without the intervention of assistance from the outside world, Belgium would starve.

Amid the initial chaos of German occupation in August and September 1914, local volunteer relief organizations arose to cope with the food problem and care for the destitute. The various committees successfully provided stopgap measures; however, their resources were limited, and the food stocks were rapidly diminishing. Panic buying, exorbitant price increases, the cessation of usual food imports, and growing friction between the military authorities and Belgian communal officials made the work more difficult. All of these developments produced a situation of extreme gravity. A strong, unofficial, independent organization that could command greater resources and enjoy greater freedom of action was needed. The chief figures in the organization of this new committee were Ernest Solvay, one of Belgium's wealthiest citizens, and Emile Franqui, a director of the Société Générale de Belgique (the most important financial establishment in Belgium).

Coincidentally, in early August, an American committee had been organized in Brussels to aid Americans stranded by the war, assisting them in returning home. The committee was supervised by the American minister to Belgium, Brand Whitlock. As the food crisis grew more serious, attempts to purchase and provide a certain quantity of supplies for the Americans in Brussels commenced. A proposal emerged, which combined the two existing relief committees to protect the remaining food stocks from being requisitioned by the occupying Germans. The Spanish minister to Belgium, Marquis de Villalobar, and the American minister, Whitlock, agreed to act as patrons.

A strong, private organization with sufficient prestige and credit to carry out large-scale operations and neutral in character aimed to garner the support of the local authorities, Germany, the neutral powers, and public opinion. It became evident that the crisis required food to be imported from abroad. Representatives embarked on missions to secure the necessary cooperation of all of the interested parties.

Diplomatic Framework

By late September 1914, the local relief committees recognized that famine was fast approaching, with food supplies nearly depleted due to requisitions, destruction, and limited distribution efforts. With no hope of assistance from the German authorities, the committees sent representatives abroad to draw attention to the dire situation in Belgium, purchase provisions, and arrange for their shipment into the occupied territories. Significant challenges emerged in obtaining permission to transport the goods to Brussels, especially British concerns that the foodstuffs would end up in German hands.

British concerns could be calmed, suggested Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), who was in London directing the American Relief Committee (established to assist Americans to return to the United States), if the shipments were transported and distributed under the protection of the American minister in Brussels. After communications between Washington and the American Ambassador in Berlin, Germany approved the relief plan. By 6 October, the British signed on the plan provided the food supplies were shipped from Britain to Brussels. All that remained was to arrange the practical details and create an organization to carry out the work.

The gravity of the developing situation, along with the enormity of the task of feeding 9 million people living in Belgium and northern France, persuaded members of the American Relief Committee to direct their services toward the interests of Belgian relief. On 12 October, it was agreed that an American committee be formed to centralize the efforts of relief and carry out the conditions imposed by the belligerents on the relief work. Hoover sent out an appeal to America through the press and a message to notify President Woodrow Wilson (in office 1913-21).

On 18 October, Hoover recommended the establishment of an American organization, with Belgian participation, in order to coordinate the various ongoing relief activities. This new committee, under the patronage of neutral ambassadors and ministers, would provide for the purchase and shipment of food, mobilize public charity throughout the world, provide members to work on the various committees outside and within Belgium, to act as the guardian of the supplies in Belgium, and to establish offices in London, New York, and Rotterdam. On 22 October, with all parties agreeing, the Commission for Relief in Belgium and northern France was created.

Belligerents' Position on Relief

The responsibility of who was to feed the Belgians and the means for performing that task lay at the heart of the initial diplomatic negotiations between the relief organization and the belligerents, particularly Germany and Britain. The economics of the warfare was as vital to each state's overall strategy as its military tactics. On 30 January 1915, the CRB chairman Herbert Hoover spelled out the arguments of both sides. Germany insisted that not only was there no provision in the Hague agreements requiring an occupying force to feed the civilian population, but that, on the contrary, the occupied civilian population could be called upon to support the occupying army. Furthermore, the German argument was that Belgium had always imported its food supplies and still possessed the resources to do so. Having opened the port of Antwerp to trade, Germany had absolved itself of the responsibility for feeding the Belgians. All that prevented Belgium from resuming its usual practices, i.e. normal flow of trade, was the British blockade. Germany's own food supply was sufficient to prosecute the war, and their duty was to feed their own people first. To take on the added burden of provisioning the Belgians would jeopardize that ability; a risk Germany would not take.

The British argument was equally persuasive. They could not allow free trade for there were no assurances that Germany would not directly or indirectly benefit. The importation of foodstuffs would relieve Germany of their moral and legal responsibilities toward the Belgian population. Britain firmly believed that economic pressure, combined with the ongoing military operations, would ultimately bring about the end of the war. Any relaxation of these pressures in effect assisted the enemy. Thus, in order for the initial relief agencies and later the CRB to operate effectively, it was necessary to provide assurances that Germany would not benefit from relief activities.

Functions, Finance & Distribution

The primary functions of the relief operations were financing, purchasing, and transporting supplies, managed solely by the CRB. It operated from a central office in London with branches in New York, Rotterdam, and elsewhere. Subsidiary committees in various countries worldwide facilitated fundraising and donations, while business offices with technical staff in key purchasing and port cities handled procurement and logistics. Through privileged telegraph and courier services, these diverse operations were coordinated through the central office in London, which maintained rapid communications with the Brussels office of the CRB. Most of the department heads and many assistants were volunteers. Paid employees only worked in specialized positions for which no experienced volunteer service was available. Governments, commercial firms, banks, and transportation companies also often provided advice and valuable services free of charge.

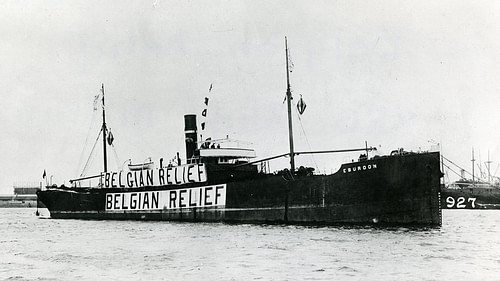

Nearly $900 million was raised by the CRB to fund relief operations, which came primarily in the form of government loans and global charity appeals. The funds allowed for the purchase and transportation of 5 million tons of food and clothing during the war, most of which came from the United States. Not all of the relief supplies reached the main distribution ports even though the CRB enjoyed a degree of immunity from the belligerents and was aided by the use of the Commission's own specially marked ships and flags.

The relief organization focused on two main activities: supplying provisions to the entire population of Belgium and Northern France and caring for the destitute. Two distinct divisions of the organization responsible for these operations were the Provisioning Department and the Benevolent Department.

The Provisioning Department purchased, transported, and distributed relief supplies for 9 million people. The purchase of foodstuffs outside the occupied territories was made with gold, and these foodstuffs, when sold through 4,731 communal stores, were paid for in local paper currency. Economic life was so disorganized and the restriction of the occupying army so rigid that the administration implemented a ration system corresponding to local needs. Each individual or family received a bread card which had to be furnished in order to receive bread on the delivery days, usually every three days. The price of bread was fixed periodically according to the cost of ingredients. Other foodstuffs were issued on a weekly basis. These other commodities, such as rice, peas, beans, bacon, and lard were primarily intended for the destitute and for those unable to pay the high prices for native supplies. The control was as rigid as for flour and bread to ensure that no one would receive more than their fair share. An individual or family received a ration card entitling them to these foodstuffs determined by the amount of need. A small charge above the actual cost was applied to the purchase of goods, and the surplus created a reserve against losses and destruction of goods and became a source of support to the Benevolent Department.

Services provided by the Benevolent Department included breadlines, canteens, clothing, and provision of temporary shelters. Special committees provided assistance to children, refugees, foreigners, young mothers, and many others. The principal outlay of funds were for the support of canteens, soup kitchens, and cheap restaurants of which one or more were established in each commune supplying free meals, or at minimal cost, to the civilian population. Of the special benevolent activities, the care of children was perhaps the most important. Not only were meals served in all the schools, but the younger children, babies, and nursing mothers were supplied with milk through the canteens.

Legacy

The work of the Commission did not cease with the agreement to an armistice in November 1918. There were no agencies, public or private, in a position to take over the Commission's functions. At the request of the Belgian and French Governments, the Commission continued its operations for several months following the armistice. By June 1920, the Commission was able to reach a settlement with both the French and Belgian governments. This settlement included the return of large sums of working capital not used by the Commission. As most of this money was given to France and Belgium in the form of US Treasury loans, it was returned to the Treasury and applied toward the reduction of these loans. The CRB would make its final payments to these governments in 1922.

Technically, the Commission for Relief of Belgium ceased to exist as an administrative structure in 1922. It would be revived in a different form during the Second World War (1939-45) to provide assistance in occupied territories. The work and efforts of the Commission have survived into the present day. In the earliest days of the occupation of Belgium, German troops burned to the ground the university library at Louvain. Lost in that deliberate act were over 200,000 books but more importantly, nearly 750 irreplaceable medieval manuscript collections. Funds from the Commission, as well as volunteer services from American engineering firms, successfully rebuilt the library. Donations of books were received from libraries and private collections from all over the United States. A portion of the excess funds was held in trust and used to establish the Belgian-American Educational Foundation. This foundation provides scholarships and fellowships to graduate students, professors, and scholars for an exchange program between the two countries.

The efforts of the CRB, Red Cross, and other relief organizations in the First World War brought about changes in the international laws governing the conduct of belligerents in its occupied territories. Prior to WWI, belligerents were not held responsible for the maintenance of the civilian population during its time of occupation. In the interwar period, new international laws were established in Geneva, directly holding belligerent countries responsible for the care and feeding of the occupied inhabitants. Perhaps, though, the most enduring legacy of the Commission's existence and its efforts was uniting countries, both belligerents and neutrals, together in a common effort to alleviate the suffering and misery of innocent peoples.