In the French Revolution (1789-1799), the Committee of Public Safety (French: Comité De Salut Public) was a political body created to oversee the defense of the French Republic from foreign and domestic enemies. To achieve this goal, the Committee implemented the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), during which time it accumulated virtual dictatorial powers over France.

At the height of its power, membership of the Committee consisted of twelve men who ruled France for ten consecutive months, from the start of the Terror in September 1793 to the fall of Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794 (with the sole exception of Hérault de Séchelles who was executed in April). The Committee succeeded in its goal to win victories in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), which it did by enacting mass conscriptions and implementing reforms on the French citizen armies. It is perhaps most famous for orchestrating and overseeing the Terror, in which 16,594 people were guillotined across France and thousands of others died without trial.

Origins

As its name suggests, the Committee of Public Safety was established at a point when the security of the infant French Republic – and indeed, the Revolution – was in jeopardy. Although the French had temporarily turned back foreign invasion at the Battle of Valmy, the list of European powers joining the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) against France was steadily growing, while large swathes of the provinces were rising in rebellion against the revolutionary government in Paris. Paranoid French citizens saw their newly won liberties hanging on by a thread, causing them to lash out and attack suspected counter-revolutionaries in bloody acts of violence like the September Massacres of 1792. Meanwhile, Revolutionary France's currency, the assignat, was rapidly depreciating in value, leading to widespread unemployment and starvation. Truly, the French Republic was being constricted from all sides; the egalitarian society promised by the Revolution was in danger of premature suffocation.

It was against this apocalyptic backdrop that the Committee of Public Safety was set up on 6 April 1793. Its primary purpose was to act as a war council and strategize the defeat of the Republic's enemies, both foreign and domestic. Yet it also served to "watch over and speed up" any government functions that could pertain to war and intelligence, such as supply manufacturing or policing (Palmer, 31). Such immense responsibility would help transform it into an executive council in all but name. Initially, however, it had no inherent power and was simply one of many committees under the broader umbrella of France's provisional government, the National Convention. Each of the nine members of the Committee of Public Safety (later expanded to twelve) was supposed to be elected by the Convention once a month to prevent certain individuals from growing too powerful, while the Committee would make weekly reports to the Convention. At least on paper, the Convention reserved the authority to censure the Committee and overrule its decisions, although this never ended up happening.

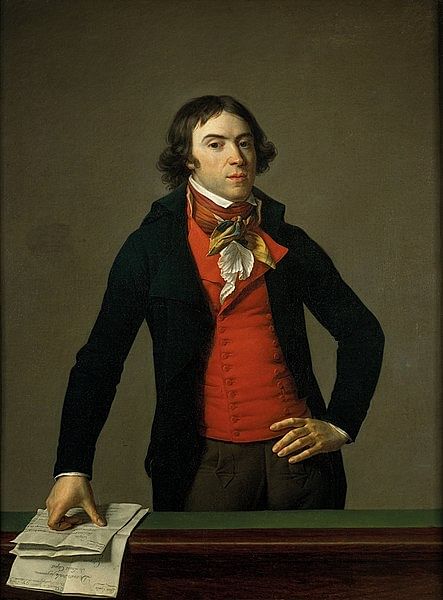

The Committee of Public Safety existed largely thanks to the efforts of Georges Danton (1759-1794), whose leadership had helped topple the monarchy during the Storming of the Tuileries Palace eight months earlier. Danton had also helped create the Revolutionary Tribunal, which was meant to try and convict counter-revolutionaries. Such an institution was essential for state security, and would hopefully prevent hysterical mobs from taking justice into their own hands; in Danton's own words, the government must be terrible "so the people don't have to be" (Furet, 220). He spearheaded the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety for much the same reason, little realizing that he had lain the groundwork for the Reign of Terror, which he would later oppose.

At first, the Committee was centered around Danton's leadership; seven of the nine-man Committee were followers of the Dantonist wing of the political party known as the Mountain. Yet Danton's star rapidly fell, as the tide of war continued turning against the French, and his overtures of peace came to nothing. In July 1793, he and his followers were forced out of the Committee, replaced with more radical members of the Mountain who were willing to go to more extreme lengths to save the Republic. By September, there were twelve of them; with one exception, these twelve would remain in power for ten consecutive months, during which time they would orchestrate and oversee the bloodiest phase of the French Revolution.

Twelve Who Ruled

Eventually, the power of the twelve eclipsed that of the National Convention; the Committee's authority soared to almost dictatorial heights until the events of 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794) led to the fall of Robespierre. The twelve did not always like one another, nor did they always see eye to eye on matters of policy. Some were certainly more popular and influential than others, with Maximilien Robespierre often recognized as the face of the Committee. Yet their administration was among the most efficient France would see during its chaotic decade of Revolution, as each man worked at the tasks at which he was most suited. Truly, in the famous words of Thomas Carlyle, "Stranger set of Cloud-Compellers the Earth never saw" (649). Below is a list of the "Twelve Who Ruled", as they are referred to by historian R. R. Palmer in his seminal book of the same name:

- Bertrand Barère (1755-1841): a sweet-talking lawyer from a family of lawyers, and a leader of "the Plain", the Revolution's equivalent of an independent party. He was the first member elected to the Committee of Public Safety and often acted as a liaison between the Committee and the National Convention, where he remained popular. Due to his many speeches and works supporting the Terror, he has been nicknamed "Anacreon of the Guillotine".

- Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne (1756-1819): an unsuccessful lawyer who was radicalized earlier in life than most of his colleagues. He was one of the most militant defenders of the Terror, famously declaring, "either the revolution will triumph, or we will all die" (Schama, 809).

- Lazare Carnot (1753-1823): a former army officer and a brilliant mathematician. He played an instrumental role in reforming the armies of the Republic and turning the tide of the War of the First Coalition in France's favor; for this reason, he was nicknamed the "Organizer of Victory".

- Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois (1750-1796): actor and playwright, known for his excitability. Along with Billaud-Varenne, he was one of the last two members added to the Committee to placate the "ultra-revolutionary" Hébertists after the insurrection of 5 September. Collot oversaw the large-scale massacre of suspects after the Revolt of Lyon.

- Georges Couthon (1756-1794): a lawyer who lost the use of his legs to meningitis, confining him to a wheelchair by 1793. He was the primary author of the infamous Law of 22 Prairial and, along with Robespierre and Saint-Just, formed an unofficial triumvirate within the Committee.

- Jeanbon Saint-André (1749-1813): a former Protestant minister, who oversaw the reconstruction of the French navy.

- Robert Lindet (1746-1825): at 46, he was the oldest member of the Committee. A lawyer, he was in charge of the National Food Commission, which oversaw agricultural and industrial production during the Terror.

- Prieur de la Marne (1756-1827): a lawyer, who oversaw the Terror in Brittany but about whom not much else is known; unrelated to Prieur de la Côte-d'Or.

- Prieur de la Côte-d'Or (1763-1832): army engineer, helped Carnot in organizing the nation's defense; unrelated to Prieur de la Marne.

- Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794): a lawyer from Arras. Self-righteous, chaste, often lost in his own thoughts. His speeches resembled lectures on morality more than anything else, but he quickly grew in popularity in the Jacobin Club because, to paraphrase Mirabeau, he truly believed everything he said. For this reason, he was nicknamed "the Incorruptible".

- Louis Antoine Saint-Just (1767-1794): a young lawyer who had been a great admirer of Robespierre's before becoming his most important ally. He made important progress in the war effort as a military commissar but is best remembered for being one of the most devout proponents of the Terror, earning him the nickname "Archangel of Terror".

- Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles (1759-1794): a wealthy aristocrat who had begun working in the Paris courts as a king's attorney at only 18. On the Committee, he often ran afoul of Robespierre, who ensured that he was tried and executed alongside the Dantonists on 5 April 1794.

In his book, Palmer points out that these Twelve were not very representative of France as a whole. With the exception of Hérault, a noble, they were entirely bourgeoisie, with no representation from the peasantry which still made up four-fifths of the French population. They were extraordinarily young for the height of power they had achieved; most of them were in their thirties with Saint-Just, the youngest, only twenty-six.

Eight of them were lawyers, and all of them except Collot had received an above-average amount of education. Except for Collot, none of them ever knew economic insecurity or had any firsthand knowledge of the wage-earning class. They were generally better off than their fathers had been, and except for the Protestant Saint-André, they had never experienced government oppression. Though they differed from one another, and from the population they presided over, the twelve were united in their common vision for a better France. They had not become revolutionaries to improve their own lives, but, instead, to mold France into a new, progressive society based on the Enlightenment ideals they all held so dear.

Day-to-Day

The National Convention, and all the revolutionary assemblies that preceded it, were characterized by their public nature. Speeches were dynamic and theatrical, proceedings were recorded and released to the public. This was not the case with the Committee of Public Safety, which met primarily at night and behind closed doors. No minutes were taken or statements recorded, no grand speeches were written down for posterity. Rumors and speculation aside, it is impossible to know the details of the conversations the twelve had with one another that shaped the course of history.

When all twelve were present, they met twice a day, briefly at 9 a.m. and more substantially at 7 p.m. Often, their secret meetings would last well past midnight. They met in an office in the Tuileries Palace, furnished with green wallpaper and a large, oval table covered with green cloth. Usually, some were absent, off on missions to Brittany, Alsace, or Lyon, or off to oversee the armies as was constantly the case with Carnot and Saint-Just. Some members, like Saint-Just, preferred being out on mission in the provinces to being cooped up in the capital while others, like Robespierre, never left Paris.

Each member worked to his own strengths. Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Couthon were the politicians, adept at speaking before the Jacobin Club and at skillfully orchestrating the Committee's judicial offensives against its enemies. Barère and Hérault secured the support of Convention deputies who may otherwise have been apprehensive about the Committee's rise to power. Carnot and Prieur de la Côte-d'Or focused their efforts on restructuring and resupplying the army, while Saint-André did the same with the navy. Lindet took care of food supplies. This division of labor was not perfect, and the members certainly had different ideas for France; an engineer like Carnot, for instance, believed Robespierre's idealistic vision of a moral, virtuous republic to be absurd. Yet they worked remarkably well together until everything fell apart in July 1794.

Road to Authoritarianism

The Committee's path to authoritarianism began on 27 July 1793, when the popular Robespierre was made a member; his obsessive quest to purge the body politic of counter-revolution would be the catalyst for the Committee's radical shift. On 5 September, the National Convention declared Terror to be "the order of the day" and also ordered the creation of a so-called Revolutionary Army to extend revolutionary justice to the provinces. 17 September saw the enactment of the Law of Suspects, a draconian measure allowing for the arrests of anyone who "by their conduct, their contacts, their words or their writings showed themselves to be supporters of tyranny, federalism, or to be enemies of liberty" (Doyle, 251). This ambiguous definition could be applied to just about anyone and led to hundreds of thousands of arrests nationwide. 16,594 of these suspects were guillotined during the Terror, with an additional 10,000 dying in prison.

On 14 September, the Committee of Public Safety was given the power to appoint deputies to other committees. Later that month, it attempted to fix the issue of overpriced bread by issuing the Law of the General Maximum which imposed strict price controls on food supplies. This also made hoarding an offense punishable by death. On 10 October, through the efforts of Saint-Just, the National Convention declared that France's government would remain 'revolutionary' (or dictatorial) until the peace. The republican Constitution of 1793 was shelved, having never been implemented, and the Committee continued to impose its will on the Convention. On 4 December, Robespierre was able to use the threat of a rumored 'foreign plot' to codify the Committee's powers in the Law of 14 Frimaire.

On the military front, the Committee enacted the levée en masse on 23 August 1793. Penned by Barère and Carnot, this was essentially a policy for mass national conscription; the wording of the decree was a declaration of total war:

From this moment on, until the enemies have been chased from the territory of the Republic, all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the service of the armies. The young men will go to combat; married men will forge weapons and transport food; women will make tents and uniforms and will serve in the hospitals; children will make bandages from old linen; old men will present themselves to public places to excite the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic. (Schama, 762)

Despite large-scale draft dodging, the levée en masse proved successful, drastically increasing the number of men enlisted across France's armies to 1.5 million by September 1794. Under its stipulations, the war effort was intensified and more efficiently organized. Additionally, Carnot ensured that the raw recruits were merged with experienced soldiers for training purposes, and imposed stricter discipline on the armies. The Committee's military reforms, as well as its tight control over the armies, led to decisive victories in the battles of Hondschoote, Wattignies, and Fleurus, which turned the tide of the Flanders Campaign in France's favor.

Moreover, the civil wars were mostly crushed by the end of 1793, their participants often subjected to brutal punitive measures by order of the Committee. Collot d'Herbois, for example, presided over mass slaughters at Lyon after its failed rebellion, while French soldiers pillaged and burned their way across the Vendée, acting on orders from Barère to turn the rebellious region into an uninhabitable desert.

Fall From Power

By early 1794, it seemed that the danger to the French Republic had mostly passed. Many believed it was time for the Terror to end and the Committee to give up its powers so the new constitution could finally be implemented. But Robespierre and his allies still believed there were enemies left to root out. To this purpose, the ultra-radical faction called the Hébertists were arrested and executed in March 1794. On 5 April, the Indulgents, a moderate faction that sought to scale back the Terror, were also guillotined; among them were Danton and Hérault.

By early summer, power within the Committee had mostly been concentrated in the hands of an unofficial 'triumvirate' who commanded the Jacobin Club, namely Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Couthon. On 10 June, the triumvirate passed the Law of 22 Prairial, which intensified the Terror by accelerating the trial phase. This began the month-long phase of the Great Terror, during which 1,400 people were executed in Paris. During this time, Robespierre began to hint that there were suspected traitors in the National Convention, as well as within the Committee of Public Safety itself. Collot and Billaud-Varenne in particular were verbally attacked in the Jacobin Club, usually the precursor to a denouncement and arrest. Those who felt most threatened by the Robespierrists decided to preemptively strike; Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Couthon were overthrown on 27 July 1794 and executed the following day. This event, usually referred to as the Coup of 9 Thermidor, not only marked an end to the Reign of Terror but also to the power of the Committee of Public Safety.

For about a year after 9 Thermidor, the Committee continued to exist, albeit in a drastically reduced capacity. Collot and Billaud-Varenne were arrested for their roles in the Terror and deported to French Guiana in 1795; Barère narrowly avoided sharing the same fate. On 22 August 1795, the French Republic adopted the Constitution of Year III, which gave France a new bicameral legislative body, the National Directory. In doing so, all the committees of the old National Convention were abolished, including the Committee of Public Safety. While it is mainly remembered today for its role in the Reign of Terror, the Committee of Public Safety certainly played a vital role in guiding the French Republic through the darkest days of the French Revolutionary Wars, inadvertently setting the stage for the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821).