Commius was an Atrebates noble during Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars (58-50 BCE) who turned from Roman ally to indomitable foe. As king of the Atrebates, Commius ably served Caesar in Britannia and Gaul before becoming one of the main leaders of the resistance in 52 BCE.

Commius commanded the Gallic cavalry at the decisive Battle of Alesia. Although defeated, he continued the fight against Rome. Hunted by the Romans, Commius fled to Britannia in 50 BCE. There he founded a new dynasty as king of the Atrebates who had immigrated to the isle.

Ally of Rome

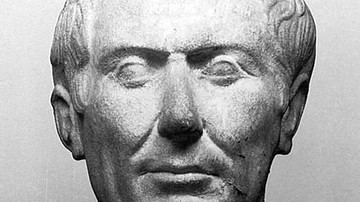

In 57 BCE, Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) defeated the Belgae tribal coalition of the Nervii, the Atrebates, and the Viromandui at the Battle of the Sabis. He thereafter installed Commius as the new Atrebates king. Caesar had great faith in Commius, who served him loyally for many years. Two years after the battle at the River Sabis, Caesar had subdued all of Gaul with the exception of some minor holdouts along the Belgae coast and in Aquitania. After annihilating Germanic tribes who were trying to migrate into Gaul in the spring of 55 BCE, Caesar prepared to punish the Briton tribes for having aided the Gauls.

When they heard about Caesar's intention through cross-channel traders, the Briton tribes decided to send envoys. Caesar received hostages from the envoys and, in turn, agreed to resolve matters in an amicable way. Commius was to accompany the envoys back to Britannia and tell everyone of Caesar's goodwill. However, upon their arrival in Britannia, Commius and his entourage were taken captive by the Britons and thrown into chains.

Caesar's fleet landed on Britannia's shores near the end of August. The Roman army overcame fierce resistance by the Britons who had gathered to oppose the landing. Seemingly cowed, the Britons asked for Caesar's mercy and desired to restore good relations. Caesar agreed on the condition that Commius be set free. Commius was released but then a storm wreaked havoc upon Caesar's fleet and delayed the arrival of the Roman cavalry. The Roman misfortune revived the morale of the Britons who renewed hostilities. Caesar repaired his fleet and came to the rescue of his Seventh Legion, which was ambushed whilst gathering grain from the countryside. The Britons next assaulted Caesar's shoreside camp but were again defeated. Commius and his 30 horsemen were in the thick of the action, helping the Roman legions repulse the Britons and harrying them as they fled. The Britons offered peace and Caesar accepted, as it was too late in the season for a major campaign of conquest.

Caesar's landing in Gaul was contested by the rebellious Morini. Since Commius had returned with Caesar, the Atrebates king may well have aided in the fighting that was required to drive the Morini away from the landing site. Commius may also have taken part in the reprisal raids as Caesar wintered his whole army among the troublesome Belgae.

Early in the summer of 54 BCE, Caesar undertook his second invasion of Britannia. Caesar crossed the Thames into the territory of the Catuvellauni, whose king Cassivellaunus headed the Roman resistance. Reduced to harrying tactics, Cassivellaunus was unable to arrest the Roman advance. When the Trinobantes went over to the Roman side and his Cantii allies faltered, Cassivellaunus sued for peace. Caesar accepted Cassivellaunus' surrender. There was news of unrest among the Belgae and so Caesar had to return to the mainland. With Commius acting as an intermediary, Cassivellaunus had to give hostages, pay a tribute, and refrain from attacking Mandubracius, king of the Trinobantes.

From the fall of 54 BCE to the spring of 53 BCE, the Belgic tribes fought Caesar in a desperate but unsuccessful attempt to rid themselves of the Roman occupiers. While Caesar crushed the Belgic tribes, Commius remained loyal to Rome. The Atrebates king was entrusted with some cavalry to watch over the freshly subdued Menapii tribe.

Gallic Resistance

During the winter of 53/52 BCE, an even greater rebellion was brewing in Celtic Gaul. Land and people had been laid to waste and hundreds of thousands had been killed by war and through starvation. The miseries inflicted upon the population fed their hatred of Rome. The chiefs met to forge plans on how best to defeat the oppressors. Among them was Commius. For his exemplary service, Caesar had granted Commius' tribe, the Atrebates, exemption from taxation, allowed them to retain their political independence, and granted them suzerainty over the Morini. Despite all this, the hardships of his fellow Gauls had reached such desperation that Commius turned against Caesar. Caesar was in Italy at the time and separated from his legions in Gaul. Now was the time to strike. However, a spy informed Titus Labienus, Caesar's prominent general remaining in Gaul, of the brewing uprising. Labienus was told that Commius was among the conspirators.

Labienus ordered Gaius Volusenus, a veteran commander who had scouted out Britannia's coastline, to kill Commius. Leading a party of centurions, Volusenus rode to Commius' home. Commius was with friends and was unaware that the Romans had been informed of his treachery. By grasping Commius' hand, Volusenus gave the centurions the signal to attack. A Roman sword bit into Commius' skull. His head covered in blood, Commius staggered back and collapsed into his friend's arms. Although blades had been drawn, both sides had otherwise not yet engaged. The Gauls wanted to avoid a fight in case more Romans showed up. The Romans, for their part, thought Commius was done for. Volusenus and his centurions departed. Commius, however, recovered, swearing "never again to come into the presence of any Roman" (Caesar, Gallic Wars, 8. 23).

By mid-52 BCE, the pan-Gallic rebellion reached its apex. Nearly all of the tribes had risen in revolt under King Vercingetorix and less than a handful remained loyal to Caesar. However, near Dijon, Caesar repulsed Vercingetorix's cavalry attack on his marching legions. Caesar blockaded the Gallic king in Alesia with a double ring of fortifications. From all over Gaul a gigantic relief army came to Vercingetorix's rescue. Commius, who was among the chief commanders, proved instrumental in winning over the Bellovaci. Although they preferred to fight the Romans at their own time and in their own way, the Bellovaci sent more troops on account of their friendship with Commius.

Upon arriving at besieged Alesia, Commius sent forth the Gallic cavalry to engage Caesar's cavalry. The fighting swept back and forth on the plain below the plateau of the fortified town. For a while it looked like the outcome could go either way until Caesar's Germanic cavalry turned the tide. The Germans routed Commius' cavalry and then decimated his archers. Subsequent attempts by the Gallic infantry to break through Caesar's blockade fared no better. Vercingetorix surrendered, sealing the fate of the Gallic resistance.

Continued Resistance

Still, the Gauls remained defiant. Rumors surfaced that many tribes were ready to simultaneously rebel all over the land, intent on overwhelming the Roman ability to respond. To prevent this from happening Caesar attacked first, laying waste to the Bituriges and Carnutes. The most serious uprising, however, was among the Bellovaci, led by their chief Correus and by Commius the Atrebatean. Four legions and auxiliary cavalry from allied tribes advanced against the insurgents. Commius managed to gain 500 cavalry reinforcements from the Germanic tribes, which did much to boost the morale of the Gauls. After cavalry skirmishes and a lengthy standoff between the Gallic and Roman camps, Correus went down fighting in a heroic last stand. Commius again gave the Romans the slip and escaped to his Germanic allies across the Rhine.

Throughout 51 BCE, Caesar continued to extinguish the last flickers of Gallic resistance and further punished the tribes that had defied him most. Caesar treated those chiefs who had stayed loyal with honor. Only Commius carried on the fight against Rome. Reduced to mere banditry, he raided Roman supply columns. As the year reached its end, the legions went into their winter quarters. The legion stationed among the Atrebates was commanded by Mark Antony (83-30 BCE). Following a skirmish between Commius and some Roman cavalry, Antony decided to hunt down Commius for good. Antony had just the man for the job, as Volusenus was attached to Antony's legion as a cavalry commander.

Volusenus managed to ambush Commius and his accompanying cavalry. The first reaction of the Gauls was to flee, but Commius rallied his men and struck back at the pursuing Roman cavalry. Bolting at the sight of the enraged Gauls, the Romans became the pursued. Catching up to Volusenus' horse, Commius thrust his spear through Volusenus' thigh. With their leader in peril, the Roman cavalry reversed its course and clashed with the pursuing Gauls. The Romans gained the upper hand in the melee that ensued. Once again, however, Commius escaped, thanks to the speed of his horse.

Commius' latest harrowing encounter with the Romans had been another close call. He had sustained another wound, and for a while, it looked like it would be fatal. Commius finally gave up on fighting the Romans. He sent hostages to Antony, asking for peace. Commius' one condition was that he would not be required to come into the presence of any Romans. Both sides agreed to and, for the time being, adhered to the terms.

Britannia

While not mentioned in Caesar's Gallic Wars, the truce between Commius and the Roman Republic appears to have broken down in 50 BCE. According to Frontinus' Strategemata, Caesar pursued Commius who fled to the Channel coast. Although the winds were favorable, the tide was out. The vessels which Commius meant to use for his escape were stranded on the flats. Commius ordered the sails to be spread regardless. The lay of the land prevented Caesar, who was still far from the shore, from seeing that the boats were still on the ground. All he could see were the sails billowing in the wind. Caesar assumed that Commius had given him the slip and broke off the pursuit.

In Britannia, Commius became allies with Cassivellaunus. In the absence of Roman garrisons in Britain, Cassivellaunus had shrugged off Roman treaty obligations. Judging by local coins struck with his name, Commius appears to have become king of a branch of the Atrebates who had settled south of the middle Thames.

Commius' son and successor Tincomarus re-established friendly relations with Rome and profited from the cross-channel trade. However, during the first decade of the 1st century CE, Cunobelinus, grandson of Cassivellaunus, advanced into Atrebates territory. Tincomarus was exiled from his kingdom. In a twist of the historical irony, the son of the Gallic resistance leader Commius fled to Rome for protection.