The conquistadors, meaning "conquerors", were Iberian military adventurers who operated as the vanguard of empires in the 15th and 16th centuries by exploring areas of the world unknown to Europeans, defeating indigenous armies, and then distributing loot and land. By the mid-16th century, conquistadors had been replaced by a more systematic colonialization process of local government and permanent settlers.

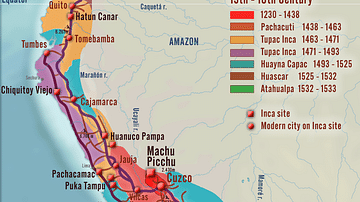

In the English language, the term 'conquistador' tends to be applied most frequently to Spanish military adventurers in the Americas, but it may also be applied to Portuguese adventurers and to areas of the Pacific and Africa. Infamous conquistadors include Hernán Cortés (1485-1547), who attacked the Aztecs in Mexico from 1519, and Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541), who began the conquest of the Inca civilization in 1532. Motivated by a lack of opportunities in their homeland and with a heady mix of religious zeal and insatiable thirst for gold, the conquistadors risked the hazards of death by warfare, disease, and misadventure to try and make their fortunes. Few succeeded and left, instead, only a blazing trail of destruction, torture, and murder.

Our revulsion today of these early imperialists should not allow us to forget that "these men evoked widespread admiration among their contemporaries" (Cervantes, xvi), an attitude that remained unchanged well into the 20th century. "Our view of their many atrocities needs to be grounded in historical context. Their world was not the cruel, backward, obscurantist and bigoted myth of legend, but the late medieval crusading world" (ibid, xvii). In short, the conquistadors were more complex than the simplistic caricature their name often conjures up in the imagination.

The Imperial Vanguard

The conquistadors were a mixed bunch, they ranged from lowly foot soldiers to leaders who claimed membership of the minor nobility. They had often gained military experience in conflicts like the Reconquista and Italian wars, but they found difficulties in finding lasting employment in Europe. Another impediment to success was that many of these men were illegitimate sons, and so they had next to no chance of social advancement. The discovery of the New World in 1492 by Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) seemed to offer an opportunity to start life anew and gain wealth in a land where any European was as equal as another. Further, even women could enjoy a freedom from European society's more rigid conventions. Women conquistadors were not common, but we do know of Maria de Estrada, the sister of the conquistador Francisco de Estrada. Maria was from Sevilla and fought in several battles in Mexico.

Monarchs were keen to exploit the resources that lands outside Europe promised, but the chances of getting there, surviving, and making it back home were small, while the cost of outfitting expeditions was huge. Better if adventurers took on the risk and costs themselves with the lure of official recognition when they got back. And the risks were certainly high, with disease and accident far more likely to end a conquistador's adventures than any enemy arrow. Fitting out a ship and packing it with men, weapons, horses, and stores was a serious investment and so required a consortium of conquistador partners to raise.

The conquistadors promised the monarchs a percentage of the gains, and they provided invaluable knowledge for state cartographers. Thus the title of adelantado was used in Spain where an expedition leader was given a license to conquer whatever they came across. Amongst these leaders, the hope of converting indigenous peoples to Christianity was all wrapped up in more worldly motivations. It is easy to discount today how important this religious zeal was for many conquistadors, both as a motivation and justification for the means they used to colonize. It is also likely true that for many, particularly the lower ranks of conquistadors, men of dubious background without many principles to care for, the adventure had one goal only: get rich quick.

Worlds Apart Weaponry

Many of the places the conquistadors explored in the Americas, Africa, and the Pacific were already inhabited, and the locals did not give up their land without a fight. However, the weapons of the conquistadors were far superior: the crossbow, cannon, arquebus, steel sword, attack dog, and cavalry proved to be all but invincible against indigenous warriors centuries behind in terms of weapons technology. This disparity allowed armies of conquistadors, which numbered fighting men in their hundreds, to defeat indigenous armies composed of warriors in their thousands. The conquistadors also exploited age-old tribal rivalries to gain invaluable allies in their wars with the empire-builders who had held sway before their arrival.

If they could afford it, conquistadors typically wore a cuirass, upper leg guards, and gauntlets of metal. As they realised their opponents were but lightly armed, armour tended to become lighter, too, since it need not protect against bullets or crossbow bolts. Humid climate conditions, in any case, played havoc with metal armour. Many conquistadors were not averse to adopting local types of armour like quilted jackets of cotton or maguey fibres which had been soaked in a saltwater solution to toughen them sufficiently to withstand arrows. A ubiquitous piece of equipment that has become a defining characteristic of conquistadors was the morion helmet with its prominent crest and upturned peak. Finally, a conquistador might carry a buckler shield, a small circle of steel used to parry blows from an attacker. Hardened leather shields were also used.

What weapons indigenous peoples had were used with great skill. An armoured conquistador was all but impregnable, but he did risk serious injury or death from a blow to an unprotected face by well-aimed darts, arrows, and sling shots. A distinct disadvantage for the defenders against the conquistadors was their approach to warfare, which was often highly ritualised. Officers wore prominent costumes and so were easy to identify and eliminate from the battlefield. Many indigenous warriors insisted on taking live captives, which often meant conquistadors could be later rescued by their comrades.

Pacification

Once an area had been conquered, even if not completely, the conquistadors shared out what loot they came across such as gold, silver, emeralds, pearls, precious woods, and animal hides. Precious metal objects were melted down for ease of distribution and because nobody cared about indigenous art or the cultural significance of pieces which had been revered for generations. By the mid-16th century, over 100 tons of gold had been stolen from the American continent. By the end of the 16th century, the Spanish treasure fleets had shipped 25,000 tons of silver to Europe.

Sharing out who got what was an inexact process where many conquistadors lost out while others gained vast riches which they distributed, along with titles and lands, to their personal followers and family members. Indeed, the greatest threat to a conquistador's gains was not from indigenous peoples but from fellow Europeans who would stop at nothing to ensure their adventures did not go unrewarded. Cortés was plagued by legal claims against him that he had not shared out his ill-gotten gains fairly. A rift between Pizarro and his second-in-command Diego de Almagro (c. 1475-1538) over the spoils of war cost Pizarro his life when he was murdered in his bed, a feud that spilled over to the next generation.

After the conquistadors had grabbed what they could, established fortresses to keep these gains, and built the churches they had promised their monarchs, the next phase of colonization was one of 'pacification'. This stage was more about long-term resource exploitation such as mining, slavery, and forced labour for plantation work. In these areas, the conquistadors had little to contribute and so their home states pushed them aside in favour of professional administrators and permanent settlers from Europe. This caused much bitterness amongst the men who had risked their lives to carve out an empire, but the materialistic aims of the conquistadors, their lack of experience in governing, and their questionable methods and harsh treatment of indigenous peoples brought them into conflict with church figures and such organisations as the Council of the Indies. This council was the governing body of the Spanish Empire, and it had two aims: resource extraction and conversion of the local people to Christianity. These aims were themselves often contradictory since a robbed person was hardly likely to look on the religion of his robber with any great admiration, but the conquistadors often murdered, tortured, or worked people to death, which meant there was no chance whatsoever of saving souls. The deaths from wars, European diseases, and maltreatment amongst indigenous peoples were staggering. In just one sorry example, Mexico saw its population plummet from 25 million in 1520 to 3 million in 1556. The same scale of devastation was seen everywhere the conquistadors went.

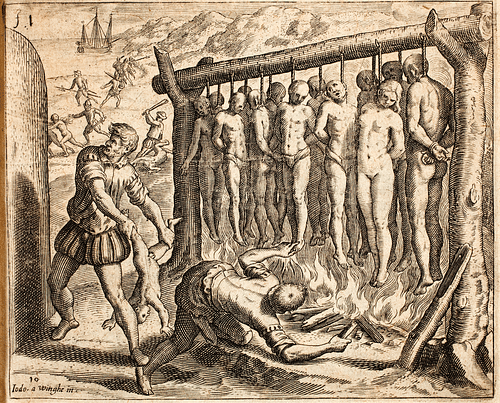

The conquistadors began to be attacked, at least in words, from their own side. Men like the Spanish Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), himself a former conquistador, wrote of the atrocities of the conquests of the Americas. Las Casas' A Very Brief Recital of the Destruction of the Indies, published in 1522, was a graphic if perhaps exaggerated indictment of the rapacious and un-Christian behaviour of the conquistadors. It certainly coloured opinion against the conquistadors and influenced those in power to replace them with a more professional system of colonial government. The conquistadors had enemies abroad, too. Other European powers, particularly the Protestant ones, could not hide their jealousy of the riches Catholic Portugal and Spain were extracting from their colonies. The English, in particular, created a masterly character assassination of the Spanish with their 'Black Legend', a term coined by the Spanish historian Julian Juderias y Loyot (1877-1918). This was a body of literature that denigrated the Spanish, an enterprise fuelled by Las Casas' work which was published in many languages and given lurid illustrations of the barbarous cruelties suffered by indigenous peoples.

Spain's New Laws of 1542 sought to alleviate some of the sufferings of indigenous people in Spanish America, but many conquistadors and their descendants rebelled against these measures. This became another reason for the state to replace conquistadors with outside officials recruited from Europe. The conquistadors and their offspring had hoped to establish a medieval system in the colonies where the land rights and titles were kept in the same family through generations, but this now could never come into practice.

With their authority replaced by colonial governors and church figures, many conquistadors now had limited choices. Most either returned to Spain with empty purses or took up more peaceful pursuits like farming, even if this was something of a step down for military men: Cortés once stated "I came here to get gold, not to till the soil like a peasant" (von Habsburg, 48). A third and much more attractive option was to keep on conquering, moving into as yet unexplored territories in the hope that new riches would be found there. This is what motivated men like Almagro to explore Chile in 1535 and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (c. 1510-1554) to wander around North America in 1540, but neither man found the fabled cities of gold they dreamed of. These expeditions, and there were many of them, caused further havoc and tragedy wherever they went and brought little in terms of wealth, but they did forge a path for future colonization by mapping areas of the world that Europeans did not even know existed. By the 16th century, the world map was, at last, taking shape, and the more lands that were added to it, the more ambitious became the rulers of Europe to claim as many pieces of it as they could.