Constantine V, also known as Constantine the Dung-named by his enemies, was emperor of the Byzantine empire from 741 to 775 CE. He enjoyed military successes in the Middle East and Balkans but his reign is chiefly remembered for his systematic persecution of any Christians, churches and monasteries which venerated icons, idols and relics. These actions and a neglect of affairs in Italy would, ultimately, see the Popes break from the Byzantine empire and join with the Franks, splitting the Christian Church in two.

Early Life & Family

Constantine was born in 718 CE as the son and successor to Emperor Leo III, a Syrian diplomat under Justinian II who had gone on to found the Isaurian dynasty which lasted until 802 CE. Constantine was crowned co-emperor with his father in 720 CE. In 732 CE he married Irene, the daughter of the Turkic tribal leader Khazar khan, although, following her premature death, the emperor would marry twice more.

Constantine had seven children in all and the birth of his first, his son Leo, would give rise to the oft-used expression, “to be born in the purple” or porphyrogennetos. The phrase derived from the porphyry, a rare purple-laced marble, that was used in the chamber of the palace at Constantinople where Leo's birth, and many subsequent ones, took place. The restriction that only royalty wore robes made with Tyrian purple dated back to Roman times and this new tradition was one more attempt to further reinforce the legitimacy of dynastic succession and deter would-be usurpers. An additional tool was Constantine's insistence that all officials swear an oath of allegiance to the royal person and heir.

Artabasdos the Usurper

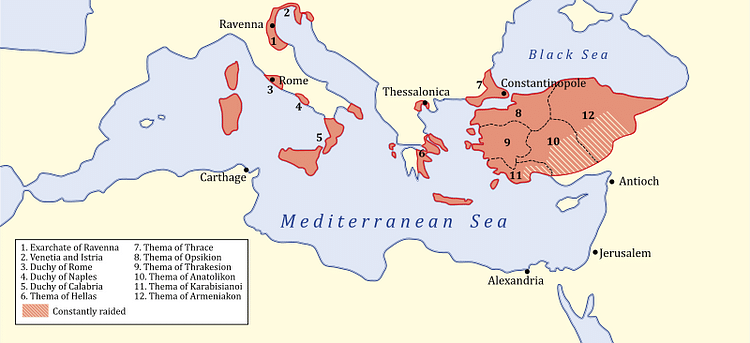

Constantine's reign got off to the worst possible start when Artabasdos seized control of the capital Constantinople in 742 CE. Artabasdos was the military governor (strategos) of the Armeniakon region in north-east Asia Minor, the second most important military province, or theme, in the empire. He was also Constantine's brother-in-law. Artabasdos was supported in his claim to the throne by Anastasios, the Patriarch of Constantinople (the Bishop), chiefly because the usurper restored the veneration of holy icons which the Church was so keen on and Constantine was so against.

Constantine moved his army against the rebels, first in the province of Opskikon and then Armeniakon. Next, he liberated Constantinople and so was able to regain his throne in 744 CE. The emperor then set about punishing those who had wronged him. Anastasios was not removed from office but was publicly whipped and sent naked through the streets of the capital riding backwards on a donkey. Artabasdos faired rather worse, he was blinded along with his two sons in a public ceremony in the capital's Hippodrome.

Constantine set about beautifying his capital and restoring it to its former glory both in architecture and commerce. He oversaw the rebuilding of the city's main aqueduct (originally built by Valens), the restoration of the Church of St. Irene, had new churches built such as the Pharos Church in the palace grounds, and rejuvenated the city's marketplaces.

Iconoclasm

As already mentioned, Constantine was a staunch opponent of the use of religious images in Christianity, just like his father before him, and he campaigned relentlessly for their destruction. For the emperor, only the Eucharist was the true image of Christ. Such was his fervour in iconoclasm (the destruction of icons and holy representations) he wrote treatises on the subject and chaired a conference of like-minded Church figures at Hieria, a suburb of Constantinople, in 754 CE. The council included 338 bishops but representatives from the pro-icon sees of Jerusalem, Antioch and Alexandria were not invited. The result was a declaration that the iconoclast position was the new orthodoxy. The historian T. E. Gregory here summarises the theological problems the issue of icons raised and why some were so against them:

Under Constantine V, Iconoclast theologians began to see connections with the theological disputes of the past 400 years: they argued that images, in fact, raised once again the Christological problems of the fifth century. In their view, if one accepted the veneration of ikons of Christ, one was guilty of either saying that the painting was a representation of God himself (thus merging the human and the divine elements of Christ into one) or, alternatively, maintaining that the ikon depicted Christ's human form alone (thus separating the human and the divine elements of Christ) - neither of which was acceptable. (212)

From 755 CE a harsh persecution of iconophiles began, led by such zealous officials as Michael Lachanodrakon, strategos of Thrakesion. Monasteries were especially targeted, with the state seizing property and Michael infamously burning down the Pelekete monastery on Mt. Olympus. Churches were hit, their precious icons and relics destroyed, and any imagery deemed unsuitable defaced - in some cases in the capital by Constantine himself - or replaced with depictions of crosses or landscape scenes. The only symbol of worship permitted was the True Cross, the wooden remains of which were in Constantinople at that time. Individuals, too, suffered and not just those in the Church but also the army and bureaucracy. Mutilations, stonings and executions were carried out on those who did not toe the line, the most infamous being of St. Stephen. Constantine was also said to have involved himself in these punishments, smearing oil on the beards of unrepentant monks and setting them on fire.

Many in the Church were very keen on their icons, though, and the emperor became deeply unpopular - so much so, a rumour was spread that when Constantine had been baptised as a baby he had defecated into the baptismal font. The emperor thus acquired his inglorious nickname of Kopronymos or “named in dung”. The emperor's reputation was similarly sullied by rumours that he was a harp-playing bisexual when in the privacy of his palace. Many art lovers past and present, no doubt, would likewise take Constantine's name in vain for all the beautiful religious art lost to posterity by his destructive zeal.

Military Campaigns

Once Constantine had made his throne safe following the Artabasdos rebellion and reorganised his army into six new regiments (tagmata), he set about expanding the empire. The historian J. J. Norwich here summarises his martial abilities,

He was a courageous fighter, a brilliant tactician and leader; of all his subjects, it was his soldiers who loved him most. (114)

First, Constantine took on the Arab world. Between 746 and 752 CE the emperor enjoyed many successes in northern Syria and Armenia, not a little helped by the civil war in, and ultimate collapse of, the Umayyad Caliphate with its capital at Damascus. The Umayyad were replaced by the Abbasid dynasty who promptly moved their capital to the safer distance of Baghdad. Peace was made with the Arabs in 752 CE.

Perhaps Constantine should have kept a more careful watch on the western half of his empire for in 751 CE the Lombards conquered Ravenna which, as an exarchate (semi-autonomous region), had acted as a protector of Byzantine interests in Italy. The defeat, along with Constantine's increasing ties with Pepin the Short (king of the Franks), the emperor's relentless persecution of icons and the decision to move Italy, Sicily and the southern Balkans away from Papal authority and put them under that of the Bishop of Constantinople, led the Popes in Rome to begin looking elsewhere for an ally, notably the Franks and Charlemagne.

In 756 CE Constantine did turn his attention to the west and the Bulgars who had long been making trouble in the Balkans. As with his predecessors and successors, though, the Bulgars proved a stubborn enemy to defeat completely. A successful campaign in 759 CE was followed by two big victories against Khan Telerig (r. c. 770-777 CE) in 773 CE, the Battle of Anchialos being especially significant in reducing Bulgar influence in Thrace. However, these did nothing to quell Bulgar ambition and the emperor twice lost fleets in storms. Constantine was still fighting them when he died of illness on campaign in 775 CE. His first son then fulfilled his purple destiny and succeeded his father as emperor Leo IV, having already been crowned co-emperor in 751 CE.

The memory of Constantine V was deliberately darkened by the Church whose icons he had so zealously attacked but this had little effect on his popularity with ordinary people during his reign. It was a popularity that withstood such disasters as the devastating Bubonic plague which hit the empire in 747 and 748 CE, wiping out a third of the population. The standard of living in Constantinople, especially, improved under his guidance and the people had access to plentiful food at reasonable prices. The emperor was also a gifted military commander, as not only his victories illustrate, but also in the famous, perhaps staged, action of a desperate mob who broke into his tomb in the Church of the Holy Apostles to plead for him to rise from his sarcophagus and bring back much-needed victories to the failing empire of the early 9th century CE. There may well have been greater Byzantine rulers over the centuries who now command more lines in the history books but few could match the passion in their beliefs that this most learned of emperors applied to his reign.