Built in the seventh century BCE, the ancient city of Byzantium proved to be a valuable city for both the Greeks and Romans. Because it lay on the European side of the Strait of Bosporus, the Emperor Constantine understood its strategic importance and upon reuniting the empire in 324 CE built his new capital there – Constantinople.

Foundation by Constantine (284 - 337 CE)

Emperor Diocletian who ruled the Roman Empire from 284 to 305 CE believed that the empire was too big for one person to rule and divided it into a tetrarchy (rule of four) with an emperor (augustus) and a co-emperor (caesar) in both the east and west. Diocletian chose to rule the east. Young Constantine rose to power in the west when his father, Constantius, died. The ambitious ruler defeated his rival, Maxentius, for power at the Battle of Milvian Bridge and became sole emperor of the west in 312 CE. When Licinius assumed power in the east in 313 CE, Constantine challenged and ultimately defeated him at the Battle of Chrysopolis, thereby reuniting the empire.

Constantine was unsure where to locate his new capital. Old Rome was never considered. He understood the infrastructure of the city was declining; its economy was stagnant and the only source of income was becoming scarce. Nicomedia had everything he could want for a capital – a palace, a basilica and even a circus – but it had been the capital of his predecessors, and he wanted something new. Although he had been tempted to build his capital on the site of ancient Troy, Constantine decided it was best to locate his new city at the site of old Byzantium, claiming it to be a New Rome (Nova Roma). The city had several advantages. It was closer to the geographic center of the Empire. Since it was surrounded almost entirely by water, it could be easily defended (especially when a chain was placed across the bay). The location provided an excellent harbor – thanks to the Golden Horn – as well as easy access to the Danube River region and the Euphrates frontier. Thanks to the funding of Licinius's treasury and a special tax, a massive rebuilding project began.

Although he kept some remnants of the old city, New Rome – four times the size of Byzantium – was said to have been inspired by the Christian God, yet remained classical in every sense. Built on seven hills (just like Old Rome), the city was divided into fourteen districts. Supposedly laid out by Constantine himself, there were wide avenues lined with statues of Alexander the Great, Caesar, Augustus, Diocletian, and of course, Constantine dressed in the garb of Apollo with a scepter in one hand and a globe in the other. The city was centered on two colonnaded streets (dating back to Septimus Severus) that intersected near the baths of Zeuxippus and the Tetrastoon.

The intersection of the two streets was marked by a four-way arch, a tetrapylon. North of the arch stood the old basilica which Constantine converted into a square court, surrounded by several porticos, housing a library and two shrines. Southward stood the new imperial palace with its massive entrance, the Chalke Gate. Besides a new forum, the city boasted a large meeting hall that served as a market, stock exchange, and court of law. The old circus was transformed into a victory monument, including one monument that had been erected at Delphi – the Serpent Column – celebrating the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataea in 479 BCE. While the old amphitheater was abandoned (the Christians disliked gladiatorial contests), the hippodrome was enlarged for chariot races.

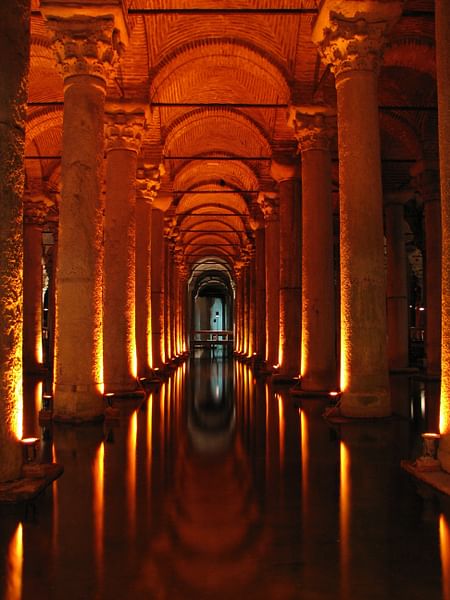

One of Constantine's early concerns was to provide enough water for the citizenry. While Old Rome didn't have the problem, New Rome faced periods of intense drought in the summer and early autumn and torrential rain in the winter. Together with the challenge of the weather, there was always the possibility of invasion. The city needed a reliable water supply. There were sufficient aqueducts, tunnels and conduits to bring water into the city but a lack of storage still existed. To solve the problem the Binbirderek Cistern (it still exists) was constructed in 330 CE.

Religion took on new meaning in the empire. Although Constantine openly supported Christianity (his mother was one), historians doubt whether or not he truly ever became a Christian, waiting until his deathbed to convert. New Rome would boast temples to pagan deities (he had kept the old acropolis) and several Christian churches; Hagia Irene was one of the first churches commissioned by Constantine. It would perish during the Nika Revolts under Justinian in 532 CE.

In 330 CE, Constantine consecrated the Empire's new capital, a city which would one day bear the emperor's name. Constantinople would become the economic and cultural hub of the east and the center of both Greek classics and Christian ideals. Its importance would take on new meaning with Alaric's invasion of Rome in 410 CE and the eventual fall of the city to Odoacer in 476 CE. During the Middle Ages, the city would become a refuge for ancient Greek and Roman texts.

Constantius to Theodosius (337 - 526 CE)

In 337 CE Constantine died, leaving his successors and the empire in turmoil. Constantius II defeated his brothers (and any other challengers) and became the empire's sole emperor. The only individual he spared was his cousin Julian, only five years old at the time and not considered a viable threat; however, the young man would surprise his older cousin and one day become an emperor himself, Julian the Apostate. Constantius II enlarged the governmental bureaucracy, adding quaestors, praetors, and even tribunes. He built another cistern and additional grain silos. Although some historians disagree (claiming Constantine laid the foundation), he is credited with building the first of three Hagia Sophias, the Church of Holy Wisdom, in 360 CE. The church would be destroyed by fire in 404 CE, rebuilt by Theodosius II, destroyed and rebuilt again under Justinian in 532 CE.

A convert to Arianism, Constantius II's death would place the already tenuous status of Christianity in the empire in jeopardy. His successor, Julian the Apostate, a student of Greek and Roman philosophy and culture (and the first emperor born in Constantinople), would become the last pagan emperor. Although Constantius had considered him weak and non-threatening, Julian had become a brilliant commander, gaining the support and respect of the army, easily assuming power upon the emperor's death. Although he attempted to erase all aspects of Christianity in the empire, he failed. Upon his death fighting the Persians in 363 CE, the empire was split between two brothers, Valentinian I (who died in 375 CE) and Valens. Valentinian, the more capable of the two, ruled the west while the weaker and short-sighted Valens ruled the east. Valens's only contribution to the city and the empire was to add a number of aqueducts, but in his attempt to shore up the empire's frontier – he had allowed the Visigoths to settle there – he would lose a decisive battle and his life at Adrianople in 378 CE. After Valens's embarrassing defeat, the Visigoths believed Constantinople to be vulnerable and attempted to scale the walls of the city but ultimately failed.

Valens's successor was Theodosius the Great (379 - 395 CE). In response to Julian, he outlawed paganism and made Christianity the official religion of the empire in 391 CE. He called the Second Ecumenical Council, reaffirming the Nicene Creed, written under the reign of Constantine. As the last emperor to rule both east and west, he did away with the Vestal Virgins of Rome, outlawed the Olympic Games and dismissed the Oracle at Delphi which had existed long before the time of Alexander the Great. His grandson, Theodosius II (408 - 450 CE) rebuilt Hagia Sophia after it burned, established a university, and, fearing a barbarian threat, expanded the city's walls in 413 CE; the new walls would be forty feet high and sixteen feet thick.

Justinian & the Nika Revolt (527 - 565 CE)

A number of weak emperors followed Theodosius II until Justinian (527 - 565 CE) – the creator of the Justinian Code – came to power. By this time the city boasted over three hundred thousand residents. As emperor Justinian instituted a number of administrative reforms, tightening control of both the provinces and tax collection. He built a new cistern, a new palace, and a new Hagia Sophia and Hagia Irene, both destroyed during the Nika Revolt of 532 CE. His most gifted advisor and intellectual equal was his wife Theodora, the daughter of a bear trainer at the Hippodrome. She is credited with influencing many imperial reforms: expansion of women's rights in divorce, closure of all brothels, and the creation of convents for former prostitutes. Under the leadership of his brilliant general Belisarius, Justinian expanded the empire to include North Africa, Spain and Italy. Sadly, he would be the last of the truly great emperors; the empire would fall into gradual decline after his death until the Ottoman Turks conquered the city in 1453 CE.

One of the darker moments during his reign was the Nika Revolt. It started as a riot at the hippodrome between two sport factions, the blues and greens. Both were angry at Justinian for some of his recent policy decisions and openly opposed his appearance at the games. The riot expanded to the streets where looting and fires broke out. The main gate of the imperial palace, the Senate house, public baths, and many residential houses and palaces were all destroyed. Although initially choosing to flee the city, Justinian was convinced by his wife to stay and fight: thirty thousand would die as a result. When the smoke cleared, the emperor saw an opportunity to clear away remnants of the past and make the city a center of civilization. Forty days later Justinian began the construction of a new church: a new Hagia Sophia.

No expense was to be spared. He wanted the new church to be built on a grand scale – a church no one would dare destroy. He brought in gold from Egypt, porphyry from Ephesus, white marble from Greece and precious stones from Syria and North Africa. The historian Procopius said:

… it soars to a height to match the sky, and as if surging up from other buildings it stands as high and looks down on the remnants of the city … it exults in an indescribable beauty.

Over ten thousand workers would take almost six years to build it. Afterwards Justinian was reported to say, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee.” Near the height of his reign, Justinian's city suffered an epidemic in 541 CE – the Black Death – where over one hundred thousand of the city's residents would die. Even Justinian wasn't immune, although he survived. The economy of the empire would never completely recover.

Medieval Constantinople (until 1453 CE)

Two other emperors deserve mention: Leo III and Basil I. Leo III (717 - 741 CE) is best known for instituting iconoclasm, the destruction of all religious relics and icons – the city would lose monuments, mosaics and works of art – but he should also be remembered for saving the city. When the Arabs lay siege to the city, he used a new weapon “Greek fire”, a flammable liquid to repel the invaders. It was comparable to napalm, and water was useless against it as it would only help to spread the flames. While his son Constantine V was equally successful, his grandson Leo IV, initially a moderate iconoclast, died shortly after assuming power, leaving the incompetent Constantine VI and his mother and regent Irene in power. Irene ruled with an iron hand, preferring treaties to warfare, aided by several purges of the military. Although she saw the return of religious icons (endearing her to the Roman church), her power over her son and the empire ended when she chose to have him blinded; she was exiled to the island of Lesbos.

Basil I (867 - 886 CE), the Macedonian (although he had never set foot in Macedonia), saw a city and empire that had fallen into disrepair and set about a massive rebuilding program: Stone replaced wood, mosaics were restored, churches as well as a new imperial palace were constructed, and lastly, considerable lost territory was recovered. Much of the rebuilding, however, was lost during the Fourth Crusade (1202 - 1204 CE) when the city was plundered and burned, not by the Muslims, but by the Christians who had initially been called to repel invaders but sacked the city themselves. Crusaders roamed the city, tombs were vandalized, churches desecrated, and Justinian's sarcophagus was opened and his body flung aside. The city and the empire never recovered from the Crusades leaving them vulnerable for the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE.