The Constitutional Convention was held at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 25 May to 17 September 1787. Spurred on by economic troubles left over from the American Revolution and compounded by the weak Articles of Confederation, delegates from twelve states met to draft a new framework of governance, the United States Constitution, which created a stronger federal government.

Background

In March 1781, the Articles of Confederation went into effect as the framework of governance for the fledgling United States, after having been ratified by all thirteen states. Under the Articles, each state essentially operated as a semi-independent republic, bound to one another in a loose 'perpetual union'. The federal government – which at the time consisted only of a unicameral Congress – was intentionally kept weak, to ensure the sovereignty and independence of the states. Congress' only real powers were those relating to war and foreign affairs, and even then, it needed the consent of at least nine states before it could declare war or borrow money from foreign lenders. The framers believed that they needed to keep the federal government weak to protect the rights and liberties of American citizens; their recent experience with the British Parliament seemed to suggest that a powerful central authority would not hesitate to squander those rights. But, before long it would become apparent that weak governments carried their own sets of issues that would be just as dangerous.

The most glaring problem was Congress' inability to levy its own taxes. Rather than raise its own money, Congress instead had to rely on donations from the states to fill the national treasury. But, especially after states began to focus on their own interests after the end of the American Revolutionary War, these donations were not consistently forthcoming. This left Congress with no funds to pay federal soldiers or meet its many other financial obligations. Nor did Congress have the power to compel the states to send money or comply with any other federal legislation. Several attempts to amend the Articles to allow Congress to raise money through tariffs were vetoed by the states. Additionally, a lack of unified foreign policy left Congress ill-equipped to deal with foreign powers, with Britain, France, and Spain all putting restrictions on American trade that the federal government could not retaliate against. Finally, Congress had been unable to respond to Shays' Rebellion when it broke out in western Massachusetts in late 1786. Although the rebellion was eventually suppressed by a privately funded army, it led to fears that future insurrections would not be crushed so easily.

For these, and other, reasons, many Americans became convinced that the Articles of Confederation were not working and that unless the Articles were revised, the United States would soon unravel. This reality weighed heavily on the minds of the delegates who met in Annapolis, Maryland, on 11 September 1786. Representing five states (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia), the delegates had merely been sent to discuss trade between states. But as their discussion touched on other issues caused by the weak Articles of Confederation, the delegates realized that something drastic had to be done. In their final report to Congress, drafted by Alexander Hamilton of New York, the delegates proposed that a constitutional convention should be held in Philadelphia the following May to discuss revisions to the Articles. On 21 February 1787, Congress endorsed the suggestions of the Annapolis Convention, and stated that it would write up a report on which changes to the Articles were necessary. Ultimately, twelve of the thirteen states decided to send delegates to the upcoming Constitutional Convention – the sole holdout was Rhode Island, which believed there was nothing wrong with the existing Articles of Confederation and refused to send delegates to amend them.

The Convention Begins

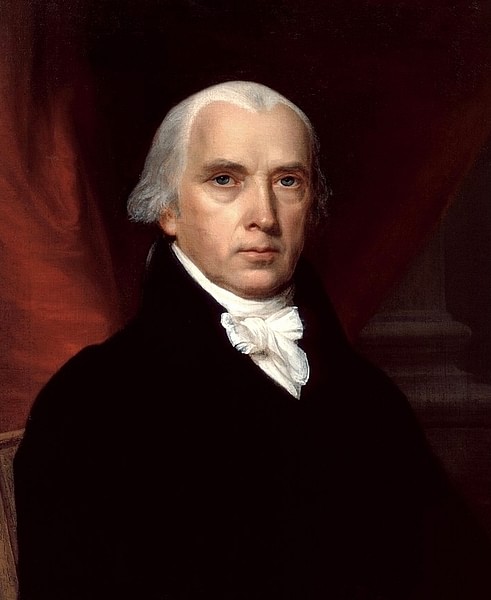

On 3 May 1787, James Madison of Virginia rode into Philadelphia, several weeks before the convention was scheduled to begin. A short, slender man with a weak voice, Madison was soon to cast a large shadow over the convention. The other delegates from Virginia were soon in the city as well. They included Edmund Randolph, the scion of an old and distinguished family currently serving as state governor, George Mason, author of the Virginia 'Declaration of Rights', as well as other prominent citizens George Wythe, John Blair, and James McClurg. In the weeks prior to the Convention, these Virginians conferred together in the house Madison was renting, coming up with a plan even as the other states' delegations trickled into Philadelphia.

Ultimately, 55 delegates would serve at the Convention. Some, like Robert Morris of Pennsylvania, John Dickinson of Delaware, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, were already recognizable figures, who had made their reputations in the revolutionary politics of the previous decades. Many others, however, were younger men still in their 30s or 40s, rising stars in the political scenes of their own states who were eager to make their reputations on the national stage; Madison and Hamilton were notable figures from this group. Amongst the delegates was a living legend, the 81-year-old polymath Benjamin Franklin, whose failing health meant that his active participation in the convention was to be limited. But the man whose attendance was by far the most anticipated arrived on 13 May, his coming marked by the ringing of bells and the cheering of crowds. This, of course, was General George Washington, who against all odds had led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolution. The most revered of his countrymen, Washington had initially been hesitant to leave his home of Mount Vernon but had been persuaded to attend by Madison, who had correctly surmised that the general's presence would lend much-needed weight to the proceedings.

A quorum was reached on 25 May and the Convention officially opened. Within the first four days, Washington was elected president of the Convention, and William Jackson was chosen as its secretary. The delegates agreed to follow a set of rules put forth by George Wythe, Alexander Hamilton, and Charles Pinckney, that each state delegation would receive only a single vote either for or against any given proposal. Finally, the Convention agreed to keep its proceedings secret from the public until it finished its work. With these procedures in place, the Convention was ready to get down to business.

Virginia Plan

On 29 May, Edmund Randolph unveiled the 'Virginia Plan', comprised of 15 resolutions that provided a blueprint for the complete overhaul of the federal government. These resolutions included establishing a 'national legislature' comprised of two chambers: representatives of the lower chamber would be directly elected by the people, while the upper chamber would be selected by the lower house. This national legislature would have the power to make laws "in all cases to which the separate states are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation" and was also empowered to veto state laws (Middlekauff, 649). A national judiciary and executive branch would both be established, their members chosen by the national legislature. Significantly, the Virginia Plan also stipulated that the amount of representation each state was allotted in this powerful national legislature would be determined by size, as measured both by a state's population of "free inhabitants" as well as the amount of taxes the state generated.

The Virginia Plan, therefore, both greatly expanded the power of the federal government and put more influence into the hands of the largest states. It is unsurprising then, that the delegations from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts – who together had almost half of the entire population of free American citizens – all supported the plan, while the smaller states of Delaware, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Maryland stood in opposition. On 30 May, a committee was established to review the Virginia Plan point by point. Headed by Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, the committee agreed to the division of the federal government into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. It also agreed that Congress should be split into a bicameral legislative body and looked to Parliament as a model – the lower chamber, the House of Representatives, would be chosen by popular vote, while the upper chamber, the Senate, was envisaged as a smaller, more selective body comprised of upper-class gentlemen.

The Virginia Plan had several points that the committee stopped to debate. The first was the nature of the office of the executive: should this consist of a single individual, or a council? Randolph spoke against a single executive, arguing that it came too close to monarchy. These concerns were soothed by James Wilson, a Scottish-born delegate from Pennsylvania, who countered that "a single magistrate is not a king" and pointed out that all states already had unitary executives in the form of their state governors (Middlekauff, 651). The delegates then voted 7-3 in favor of establishing a single executive, an office soon referred to as the President. On 4 June, the committee looked at the judiciary and voted in favor of establishing a national court that oversaw several inferior courts, with judges appointed by Congress. The main point of contention regarding the Virginia Plan, the issue of state representation, was shelved, but the committee presented the rest of its work to the broader Convention on 13 June.

New Jersey Plan

Upon listening to the committee's revised Virginia Plan, the delegates singled out two issues for further debate. The first was the way congressional representatives would be chosen, with many delegates expressing concerns over popular election. Roger Sherman argued that popular elections would make state governments irrelevant, while Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts feared mob rule, warning that, "the evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy" (Middlekauff, 652). The other major issue was, of course, that of proportional representation, which favored the interests of larger states at the expense of the small. On 14 June, William Paterson of New Jersey stood and asked for an adjournment, to allow the delegates to establish a "purely federal" plan. This was agreed to and the following day, 15 June, Paterson presented his own outline, which was soon to be known as the 'New Jersey Plan'.

Written in conjunction with delegates from Delaware and Maryland, the New Jersey Plan insisted that Congress remain a unicameral assembly where each state was equally represented, no matter its size. There would be a plural executive, rather than a unitary one, that would appoint a judiciary that had limited powers. But despite these changes, the New Jersey Plan still called for an enlargement of the Articles of Confederation; Congress' legislation would be the "supreme law of the land", and the executives would be empowered to compel states to obey (Middlekauff, 653). For the rest of June, delegates hotly debated Paterson's plan, particularly regarding equal representation; Madison pointed out that New Jersey itself might one day regret giving every state equal representation, as new states were bound to emerge from the unsettled West. By giving these states equal authority when their populations were still small, Madison feared the rise of a tyrannical minority that "ever might give law to the whole" (Middlekauff, 654). On 19 June, a vote was held, and the delegates ultimately decided against adopting the New Jersey Plan. Having chosen the Virginia Plan, it was now left to the delegates to work out the details so that it would be acceptable to all attendant states.

Connecticut Compromise & Three-Fifths Compromise

Even after rejecting the New Jersey Plan, the delegates remained deadlocked over the issue of representation. Passions ran high, and some delegations even threatened to pull out of the Convention. It fell to the delegates from Connecticut – Oliver Ellsworth, Roger Sherman, and William Samuel Johnson – to carve a middle path. Ellsworth pointed out that, under the current confederation, each state existed as a sovereign republic; to ask the small states to surrender equal representation was to ask them to give up their sovereignty. At the same time, it did make sense for proportional representation to play some role in the federal government. "We are running from one extreme to the other," Ellsworth said. "We are razing the foundations of the building when we need only repair the roof" (Middlekauff, 657).

The solution proposed by the Connecticut delegates – known as the 'Connecticut Compromise' or the Great Compromise' – was this: the House of Representatives would be chosen by proportional representation while the Senate would adhere to state equality. While the small states were happy with this compromise, the large resisted it. Wilson still argued wholly in favor of proportionality, asking, "for whom are we forming a Government? Is it for men, or for the imaginary beings called States?" (Middlekauff, 658). Madison took the argument a step further, arguing the states were never sovereign and always owed subservience to Congress. A vote on the compromise was held on 2 July, with the Convention split five states against five; Georgia was divided on the issue, and the New York delegation had gone home.

To further scrutinize the issue of representation, a 'Grand Committee' was established, consisting of one delegate from each state. The members of the committee were chosen by ballot; Paterson and Ellsworth, outspoken champions of the smaller states, were selected, while Madison and Wilson, the two loudest proponents of the large, were not. After a three-day recess to observe the Fourth of July, the Grand Committee agreed that every state would have an equal voice in the Senate, with each allotted three senators (this was later changed to only two senators per state). To account for proportionality, it was decided that one member of the House of Representatives would be chosen for every 40,000 inhabitants and the House of Representatives would have the exclusive authority to originate bills dealing with raising money.

When the Grand Committee presented this plan to the Convention on 5 July, it raised a glaring question that could no longer be ignored: how would slaves be counted in proportion to a state's overall population? Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina argued that slaves should be fully counted on the basis that they generated much of the states' wealth. This, of course, would grant more representation to Southern states like South Carolina and Georgia, which had large populations of enslaved people. The Northerners resisted this notion but, to avoid alienating the Southern states entirely, offered a Three-Fifths Compromise, whereby only three-fifths of the enslaved population would be counted. This was agreed to, and the Connecticut Compromise was finally adopted on 16 July.

Drafting the Constitution

On 26 July, the Convention adjourned to allow a Committee of Detail to write the first draft of the Constitution. Chaired by John Rutledge, the committee presented its draft when the Convention reconvened on 6 August. Much to Madison's disappointment, the committee had gotten rid of the provision that allowed the national government to veto state laws but had generally adhered to the structure of government as recommended by the revised Virginia Plan and the Connecticut Compromise. There were more debates to be had about the finished product, however, with Southern delegates lobbying for a clause that would indefinitely protect the slave trade. Northerners were unwilling to accept that, and it was decided that Congress could not try to prohibit the slave trade prior to 1808. This compromise left a bad taste in the mouths of many delegates who wished to see an end to the slave trade. But Madison summed up the opinions of many of his colleagues by stating, "Great as the evil [of slavery] is, a dismemberment of the union would be worse" (Middlekauff, 666).

On 31 August, the Convention established a Committee on Postponed Parts, to address any issues that remained open-ended. It was this committee that shortened presidential terms from seven years to four and decided that the president would be elected by an Electoral College rather than by direct vote. The committee also created the office of vice president, whose only specified duties were to preside over the Senate and cast tie-breaking votes. Important powers previously allotted to the Senate, such as the making of treaties and appointment of ambassadors, were transferred to the president. On 8 September, another committee was selected to write a new draft of the Constitution. Gouverneur Morris did most of the work in the rewrites and is therefore regarded as the primary author of the Constitution.

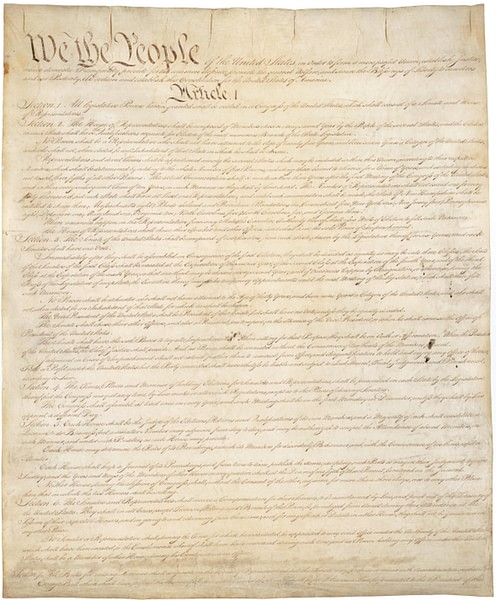

Shortly before the document was signed on 17 September, it was proposed that the size of congressional districts be reduced; in one of his only contributions to the discussion, Washington voiced his support, and the measure was adopted. Thirteen delegates refused to sign including George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, and Edmund Randolph; although Randolph had been the one to propose the Virginia Plan, he claimed to now disapprove of how powerful the federal government had become, although his detractors would argue that he was only trying to salvage his political career. The other 39 delegates affixed their signatures to the Constitution without additional debate.

Conclusion

After the Convention, the Constitution was sent to the states for ratification. This sparked fierce debate between supporters of ratification, called Federalists, and opponents, the Anti-Federalists; a common Anti-Federalist argument was that the Constitution gave the federal government too much power and offered no guarantee of individual liberties. Nevertheless, the Constitution was ratified by the necessary nine states by June 1788 and went into effect the following March. To soothe the concerns of some Anti-Federalists, a Bill of Rights was added in 1791. The Constitution drafted and signed in Philadelphia in 1787 remains in effect today, albeit with 27 amendments added over the years.