The Council of Chalcedon was called in 451 CE by the Roman Emperor Marcian (r. 450-457) to settle debates regarding the nature (hypostases, "reality") of Christ that had begun at two earlier meetings in Ephesus (431 CE and 439 CE). The question was whether Christ was human or divine, a man who became God (through the resurrection and ascension) or God who became a man (through the incarnation, "taking on flesh"), and how his humanity and divinity affected his essence and being, if at all.

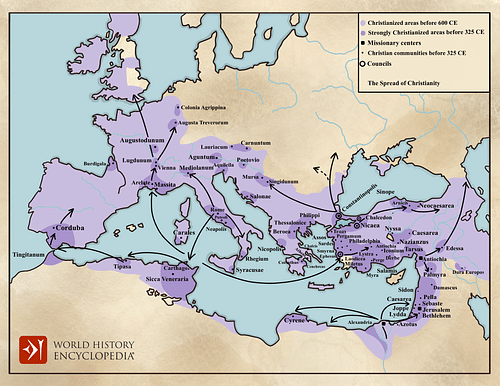

Shortly after Emperor Constantine's conversion to Christianity in 312 CE, an Alexandrian presbyter, Arius, applying logic, had simply taught that if God created everything in the universe, then at some point he must have created Christ. This caused debates and even riots throughout the cities of the Roman Empire. If Christ was a creature, then he was subordinate to God. Seeking empire-wide unity, Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) called for a council meeting at Nicaea in 325 to settle the matter.

The First Council of Nicaea produced what became known as the concept of the Trinity. This concept expressed the belief that Christ was of the identical essence of God, who had manifested himself in the earthly Jesus of Nazareth. It produced the innovation of a creed that dictated what all Christians should believe. The Nicene Creed was now enforced by the legions of the Roman emperor, and Arianism was condemned as heresy. However, those who sided with Arius continued to incorporate his teachings in their communities. One of Constantine's sons, Constantius II (r. 337-361 CE), was an Arian Christian.

With the beginning of the barbarian invasions in this period, Christians were urged to be patriotic Christians, in line with the Imperial Church. However, the Antiochene and Alexandrian communities continued to debate which emperors had such authority (legitimacy), depending upon their views of continuing Arianism at their courts and other topics. The other problem was that the Council of Nicaea only addressed the relationship between God and Christ but said nothing about his nature.

Struggle Among the Sees

For several centuries, Christian bishops had competed with each other in relation to who had the authority to dictate beliefs and rituals for all Christians. The major sees (dioceses) of bishops were Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Rome. The First Council of Constantinople in 381 elevated Rome above all others (as the site of martyrdom of Saint Peter and Paul the Apostle). Alexandria, which had several Christian schools of philosophy, saw this as an insult to their prestige. Antioch resented it because they claimed their community was the first to be called Christians (from Luke's Acts of the Apostles). Jerusalem was the most insulted, as this was the site of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth and his resurrection. Thrown into this mix were three more heresies that ultimately required more imperial anathemas and dictates: Paulinism, Novatianism, and Nestorianism.

Paulinism

Paul of Samosata (200-275 CE) – from which we have the term "Paulinism" – was the Bishop of Antioch from 260-268 CE. In the earlier debates regarding the Trinity, he claimed that Jesus was born a man but infused with the divine logos. The logos was the principle of rationality (taught by the Greek philosopher Plato, 428/427-348/347 BCE) that connected the highest god to creation on earth often translated as "word," as in the Gospel of John: "The Word became flesh" (John 1:14). Earlier Christians had taught this same logos concept, but the schools of philosophy were incomplete because they did not recognize that the logos was in fact Christ in a preexistent form of divinity.

Through this adoption, Jesus was not a god who became man, but a man who became God. As a man, Jesus shared God's divine will. Paul was condemned as a heretic after the official doctrine of the Trinity was established at Nicaea, but there were followers of his teaching throughout the empire. Paulinist baptism was deemed unacceptable and required rebaptism.

Novatianism

Novatian (c. 20-258 CE) was a Christian theologian who refused to readmit any Christian who had lapsed during the persecution of Decius (251 CE). Some Christian bishops had sacrificed to the gods to avoid execution, and their forgiveness had to await God in the final judgment. Novatian believed that membership in the Church was not required for salvation, but as the Church is made up of saints, readmission of these sinners would threaten the community. Novatian's followers extended the idea of no readmission to all who committed mortal sins such as idolatry, murder, and adultery. Many of them also forbade remarriage after a divorce or widowhood.

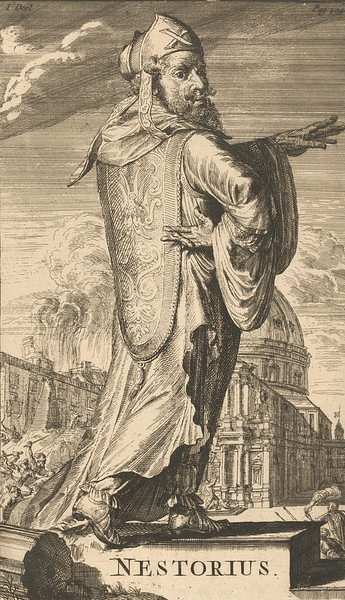

Nestorianism

Nestorius (386-450 CE) was the Archbishop of Constantinople from 428-431 CE. Among other issues, his most controversial teaching was a rejection of the elevation of Mary as Theotokos ("God-bearer" referring to the 2nd-century CE claim that Mary was elevated because she carried divinity in her womb). Rejecting Theotokos, he preached Christotokos ("Christ-bearer"). Whether he intended to or not, by the 5h century CE, Nestorianism was denounced as teaching two distinct hypostases in the Incarnate Christ, or two separate realities, one human and one divine.

In addition to these views, Jewish-Christian communities (such as the Ebionites) still existed, especially in the Eastern Roman Empire. These were Jewish followers of Christ who still argued for the full conversion of Gentiles, including circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath observance. In their view Jesus was born human, but God's revelation in him created a man of moral excellence. He was vindicated by his death and exalted to Heaven.

The Choices at Ephesus

Emperor Theodosius II (r. 402-450 CE) called the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE to settle all of these matters. First and foremost, all Jewish-Christian views were condemned as heresy. Secondly, the remaining views and communities of Gnostic Christians, who taught that Christ did not become human, he only appeared (docetism) as human so that his humanity was denied, were condemned.

The Roman delegates held to their claim that two substances were joined in a single person, including a rational soul (the logos), following the teachings of Plato. The delegates from Antioch preferred the tradition of the gospels of a more human Jesus. Jesus' humanity meant that he could be more sympathetic to the struggles of humans. Divine elements were present in the human Jesus, but full divinity occurred only at his resurrection and exaltation.

The remaining Arians in Alexandria, who taught that Christ was subordinate to God, claimed that if the "word" (logos) can combine with flesh, it receives sense impressions. Therefore, it is mutable (changing), not identical to God. The union between the divine and the human in Jesus was a true communication. In Christ, the word/spirit and the body and soul are thus joined to the divine and cannot be acted on or changed, but this was a union without forming a new nature.

Throughout the proceedings, bishops argued over the extent of Jesus' humanity. Bishop Clement of Alexandria had earlier claimed that Jesus lacked human passions. Rather, the line in the Gospel of John that "Jesus wept" (11:35) was an allegorical symbol of the loss of God's plan for humans. Others taught that Jesus' body was different, purer than all other humans. As an original soul before creation, the soul of Jesus was different than human souls. They even debated if Jesus physically ate (an allegory or metaphor?) or performed other human functions (such as defecation).

All these theologians agreed on the union of divinity and human but disagreed on the physics of how it was achieved. In relation to salvation, Athanasius of Alexandria (d. 373 CE) claimed that it was not to give God an opportunity to participate in human life but so that humans could participate in the divine life, for man to become God.

At the Council of Ephesus, Nestorius' views were supported by Bishop John of Antioch and Cyril of Alexandria (who had a monastery). Bishop Celestine of Rome opposed him, but then Cyril of Alexandria sent Nestorius a letter with twelve anathemas that had to be accepted and included in all Alexandrian theology. Both Nestorius and John of Antioch were late in arriving and were condemned in abstentia. John arrived four days later and condemned Cyril. Bishops' legates arrived from Rome in the next few days. They suggested ratifying the condemnation of Nestorius but removing the ban on John's group and readmitting them.

Ephesus was notorious for the constant excommunications and charges of anathema by bishops on both sides. Theodosius II threw most of them in prison, but Cyril talked his way out. All three major heresies (Paulinism, Novatianism, and Nestorianism) were condemned, but the First Council of Ephesus essentially resolved nothing. A second one was called in 439 CE. The conclusion was that the duality of natures existed only in the ideal moment, before the Incarnation. The conclusion of the Second Council of Ephesus was that after the union, there was only one nature.

Council of Chalcedon (451 CE)

After the death of Theodosius II, those discontented with the councils of Ephesus still objected and argued different views. In 451 CE, Emperor Marcian called for the Council of Chalcedon (near Constantinople). The purpose was to finally settle the issue of the two natures of Christ and how to word the doctrine of Incarnation. It was attended by 520 bishops and their entourages and was the largest and best-documented of all the councils. Marcian wished to bring proceedings to a speedy end and asked the council to make a pronouncement on the doctrine of the Incarnation. It was decided that no new creed was necessary.

The Council issued what was called the Chalcedonian Definition or the Chalcedonian Confession:

Following then, the holy Fathers, we all with one voice teach that it should be confessed that our Lord Jesus Christ is one and the same God, the Same perfect in Godhead, the Same perfect in manhood, truly God and truly man, the Same (consisting) of a rational soul and a body; homoousios with the Father as to his Godhead, and the Same homoousios with us as to his manhood; in all things like unto us, sin only excepted, begotten of the Father before the ages as to his Godhead, and in the last days, the Same, for us and for our salvation, of Mary the Virgin Theotokos, as to his manhood. One and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, made known in two natures [which exist] without confusion, without change, without division, without separation; the difference of the natures having been in no wise taken away by reason of the union, but rather the properties of each being preserved, and [both] concurring into one Person and one hypostasis (essence)—not parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son and Only-begotten, the divine Logos, the Lord Jesus Christ; even as the prophets from of old [have spoken] concerning him, and as the Lord Jesus Christ himself has taught us, and as the Symbol of the Fathers has delivered to us. (quoted in Herring, 324)

The conclusion was reached that the two natures of Christ remained distinct in the union; neither nature was diminished in any way through their joining. The Council also issued 27 disciplinary canons governing church administration and hierarchy (to stem the lifestyles and corruption of the clergy). Canon 28 declared that the See of Constantinople had the patriarchal status with equal privileges to the See of Rome.

Consequences

The immediate result of the Council created more schisms. Some bishops claimed that the declaration of two natures was equivalent to Nestorianism. The Alexandrian churches did concede two natures from the beginning, but they emphasized the divine nature as dominant. The Alexandrians were now labeled as monophysites ("one nature") and thus heretics. This was technically not their position, but they broke from both Constantinople and Rome and created the independent Coptic Christian Church of Egypt with their own Pope. They suffered persecution and executions until the time of the Islamic Conquest, which granted them status as "people of the Book," Jews and Christians.

In the East, the Nestorian survivors carried his teachings into Persia and other regions of the Byzantine Empire and beyond. Nestorian communities existed along the Silk Road into China and India. Periodically vestiges of heretical teachings arose, and so there were continual rounds of excommunications and denouncements from Constantinople. The existence of these divergent communities as well as other issues ultimately contributed to the separate creation of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The two main Churches separated in 1054, into Latin Christianity (the Catholic Church) and Orthodox Christianity.

Many modern Christians have difficulty understanding some of the more esoteric details of these debates and why such arguments led to condemnation and executions, but in the historical context of the ways in Christianity was transforming the late Roman Empire, the stakes were high; differences in interpretation jeopardized the very concept of salvation for Christians.

When Christians began electing bishops (overseers) in their communities, a unique innovation was added in that these bishops had the power to forgive sins on earth (from Matthew's story of Jesus commissioning Peter for this role). The bishops received this power through ordination, or the sacrament of the laying on of hands, which spiritually translated the power of Peter down to his successors. What became the sacraments (baptism, communion, marriage rituals, etc.) were now under the authority of the bishop. What made these sacraments different from other rituals was the belief that the spirit of God was literally present at that moment. Debates swirled around the problem of whether it nullified the sacraments if a bishop were accused of not following the dictates of the Imperial Church.

In the 2nd century CE, Christians had invented the concepts of orthodoxy ("correct beliefs") as opposed to heresy (from the Greek haeresis, a "school of thought") as anything that differed from their views. When Constantine I converted, he became both head of the Roman Empire as well as the Church. Anyone who now opposed the Christian beliefs of the emperor was a heretic, which meant being guilty of treason. Then as now, interpretations were crucial for the relationship between church and state. All of our literature from this period was written by the elite, upper-class, educated Christians. How these teachings were read or understood by the majority of uneducated Christians remains unknown, but average Christians would have been caught up in the many coups and civil wars resulting from these debates, in the various armies of contending emperors and bishops.