Crates of Thebes (l. c. 360-280 BCE) was one of the most important Cynic philosophers of ancient Greece. He was born to a wealthy family in Thebes but gave away his inheritance after realizing the futility of material possessions. He then moved to Athens where he studied philosophy with Diogenes of Sinope.

Diogenes of Sinope (l.c. 404-323 BCE) was and advocate of complete truth in one's daily life and regarded manners, etiquette, and rules as traps which only led to spiritual bondage and misery. True freedom, Diogenes claimed, lay in rejecting society's constructs and values and living simply according to one's own values. Crates admired Diogenes greatly and emulated his lifestyle.

Like Diogenes, Crates lived on the streets, owned nothing, and lived his philosophy very publicly. He refused any offers which seemed like luxuries to him and maintained a simple lifestyle which enabled him to accept any change in circumstance with equanimity. His most famous student was Zeno of Citium (l.c. 336-265 BCE) who founded the Stoic School of philosophy which would later have a significant impact on the culture of Rome and later cultures and civilizations up to the present day.

Early Life & Conversion

Crates grew up in Thebes, the son of a wealthy family and, as a matter of course, would have followed in his family's business. One night, however, he saw a play of the Tragedy of Telephus, which relates the story of how King Telephus, the son of Heracles, was wounded by Achilles. The wound would not heal and, when Telephus consulted the oracle, he was told it could only be healed by the one who inflicted it. Telephus disguised himself as a beggar and went to Achilles' camp, where he managed to convince Achilles to heal him with the same spear that wounded him.

No ancient sources explain what it was about this play that so moved Crates, but perhaps it was that not even a king, and son of the demi-god Heracles, was immune to pain and loss. It could also be that when Telephus assumed the disguise of the beggar, he was more effective in achieving his goal of being healed than when he was a king. Whatever it was that moved him so profoundly, after the play Crates dispersed his personal wealth to the people of Thebes, left his family, and went to Athens to study philosophy.

Life in Athens

To say that Crates "studied" with Diogenes of Sinope gives the impression of a master teaching a student, perhaps in a classroom; this image is far from the truth of the relationship between the two men. Diogenes lived his philosophy daily on the streets of Athens, and Crates would have learned as much from his example as from any of his lectures (if he even gave lectures).

Diogenes' philosophy was developed from that of his teacher, Antisthenes (l. c. 445-365 BCE), founder of the Cynic school,who had been a student of Socrates, and emphasized the rejection of material wealth, objects, and social status in favor of a life lived simply and in accordance with nature. There was no need for personal possessions according to the Cynic view, because one was only going to lose them and, more importantly, they distracted one from the act of living one's life.

This same could be said of social status or education (in the formal understanding of the word) or social etiquette; all of these concepts were unnatural and devised by human beings to help them give shape and order to the world but, really, they were artificial concepts that separated people from the possibility of living honest lives. The famous story of Diogenes of Sinope looking for a "human being" on the streets of Athens by holding up a lantern to people's faces in broad daylight is an example of how the Cynics tried to wake people up from the dream world that most lived in. Crates followed Diogenes' example but, it seems, had a much gentler approach.

The ancient writer Diogenes Laertius (l.c.180-240 CE), who wrote on the lives of many Greek philosophers, claims that Crates was known as "the door opener" because he would regularly walk into people's houses to give them counsel, uninvited, and then leave when the situation was resolved. He was a physically unattractive man but had such a good spirit and was always so cheerful that the people of Athens welcomed him into their homes.

One of the best examples of Crates' "door-opening" concerns a young man who would become a student of his and, later, his brother-in-law. Metrocles of Maroneia (l. c. 4th century BCE) was studying formal philosophy at Aristotle's Lyceum under the teacher Theophrastus (l. c. 371 - c. 287 BCE) who ran the school in the same way Aristotle had and required students to give lectures on the subjects they had studied. The historian William D. Desmond relates the tale of Metrocles' enlightenment as found in the work of Diogenes Laertius:

Once while declaiming, Metrocles farted audibly and was so ashamed that he shut himself away from public view and thought of starving himself to death. But Crates visited him, fed him with lupin-beans, and advanced various arguments to convince him that his action [of farting] was not wrong or unnatural and had been for the best in fact. Then Crates capped his exhortation with a great fart of his own. "From that day on Metrocles started to listen to Crates' discourses and became a capable man in philosophy" (DL 6.94). Such is Diogenes Laertius' laughable deadpan conclusion, and this is the Cynic's point: everything is laughable, there is nothing serious in mortality, and one should not wrinkle one's brow with Aristotelian jargon or be ashamed of any natural functions. (28)

To Crates, anything that did not proceed from nature was a trap and, among the many, were the traps of social etiquette, formal education - which only cluttered one's mind with useless facts - and, especially, social status and wealth. He is said to have driven his family away with a stick when they came to Athens to return him to his former life of ease and luxury back in Thebes.

Crates & Hipparchia

Metrocles was the son of a wealthy Athenian family who were no doubt displeased when he dropped out of the Lyceum to live on the streets and follow Crates' teaching. Their displeasure definitely increased, however, when Metrocles introduced Crates to his younger sister Hipparchia (l. c. 350 - 280 BCE). Hipparchia of Maroneia was a very enviable match in the elite circles of Athens and had many suitors. When she met Crates, however, she refused all of them and said she would marry only Crates or else kill herself.

Her parents asked Crates if he would come reason with her and talk her out of this decision. He arrived at the house, disrobed and, standing naked in front of her, said, "Here is the bridegroom and these are his possessions - choose accordingly." Instead of dissuading Hipparchia, this only made her love him more and she left her family and wealth to marry him and live with him in poverty on the streets. They consummated their marriage on the porch of a public building in downtown Athens reasoning, as they did in all things, that if there was nothing unnatural about sex in private, there was nothing wrong with it in public. Hipparchia would bear Crates two children, a son and daughter, and lived with him for the rest of his life.

Crates emphasized non-violence in his teachings and, as a part of that belief, felt that no one should have to submit to another's will in marriage just because social custom and the laws of the city encouraged such behavior. One should strive to be free in all things and master oneself and one's own problems before worrying about others and theirs. He was known to never drink wine or any intoxicant, but only water, and to eat only what was necessary to live, but never to excess. In summer he wore a winter cloak to teach himself to bear adversity in the body and, in winter, only rags. He died of natural causes in his old age on the streets of Athens.

Legacy

Both Crates and Hipparchia are said to have written a significant number of philosophical works but very few of Crates' lines, and none of Hipparchia's, exist in the present day. Hipparchia traveled and taught daily with Crates, wearing men's clothing and conversing with males as an equal. It is thought she took over teaching his students after his death. Crates taught completely by example, and it is thought his lectures were actually discussions and his classroom most certainly the streets of Athens.

Among his pupils was Zeno of Citium, a former merchant of means, who was shipwrecked on one of his trips to Athens. He found a copy of Xenophon's Memorabilia in a book store and was so impressed by the figure of Socrates in the work that he abandoned his business and devoted himself to philosophy, studying first with Crates.

Zeno developed the Cynic philosophy into the philosophic discipline of Stoicism which would be further developed by the Roman philosopher Epictetus (l.c.50 CE-130 CE) and become one of the most important and influential belief systems of ancient Rome. Stoicism, in time, came to influence later philosophical systems and became especially popular in the 1960's CE among the counter-culture who were largely introduced to Stoic concepts through Henry David Thoreau's Walden (published in 1854 CE), which emphasized the importance of living one's life truly through simplicity.

Crates' vision of a world based on justice, non-violence, and simplicity of living, as developed by Zeno, may have also influenced Thoreau's other work, Civil Disobedience (published 1849 CE), which inspired Gandhi in his non-violent resistance to British rule in India and, later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s civil rights movement in the United States of America.

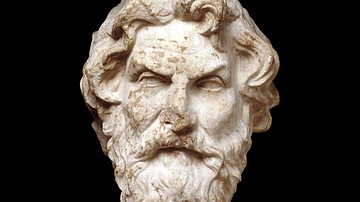

![Crates of Thebes [Painting]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/2913.jpg?v=1732987687)