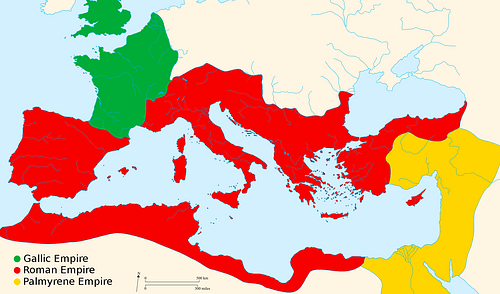

The Crisis of the Third Century (also known as the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 CE) was the period in the history of the Roman Empire during which it splintered into three separate political entities: the Gallic Empire, the Roman Empire, and the Palmyrene Empire. These breakaway empires, as well as the social turmoil and chaos which characterized the period, resulted from a number of factors: a shift in the paradigm of leadership following the assassination of the emperor Alexander Severus (222-235 CE) in 235 CE by his own troops, increased participation by the military in politics, lack of adherence to a clear policy of succession for emperors, inflation and economic depression caused by a devaluation of currency under the Severan Dynasty, increased pressure on the emperor to defend the provinces from invading tribes, the plague which heightened fears and destabilized communities, and larger armies which required more men and decreased the agricultural labor force.

After the assassination of Alexander Severus, the empire would see over 20 emperors rise and fall in the almost 50 years between 235-284 CE as compared with the 26 emperors who reigned from the time of Augustus Caesar (27 BCE - 14 CE) to Severus, 27 BCE - 235 CE, a period of over 250 years. The empire was restored through the efforts of Emperor Aurelian (270-275 CE) whose initiatives were developed further by Diocletian (284-305 CE) who is credited with ending the crisis and ensuring the future survival of the empire.

The Crisis Begins

Septimus Severus (193-211 CE), who founded the Severan Dynasty, began the policy of placating the military and buying their loyalty through increased pay and other measures. Septimus Severus raised a soldier's pay from 300 to 500 denarii annually, which was long overdue, but at the same time enlarged the armed forces in order to meet the challenges from beyond the borders which Rome now faced. In order to pay his soldiers, he debased the currency by adding less precious metal to the coinage. Although this initial debasement did not cause any economic problems, it set a precedent for later emperors to do the same.

Further, by playing to the military, Severus weakened the traditional standing of the role of the emperor and made the position dependent on the loyalty of the army. Even though the emperor always relied on the support of the military to one degree or another, the courting of the military by the emperor became far more pronounced. Although throughout the Severan Dynasty the danger of this shift in the traditional model – in which the emperor was supreme by right of succession – posed no problem, it would become apparent after the death of the last emperor of the dynasty, Alexander.

Alexander Severus was dominated by his mother, Julia Mamaea, and grandmother, Julia Maesa, who directed him from the start of his reign as a young boy. In spite of a number of positive policies initiated, he was never able to break free from the hold of his mother and this would eventually lead to his downfall. Alexander's mother was already unpopular with the troops because of the pay-cuts she had initiated in order to save money for her own purposes. As it became more and more apparent that Alexander was only a puppet of his mother, the troops lost respect for him, and the final insult came on a campaign against the German tribes.

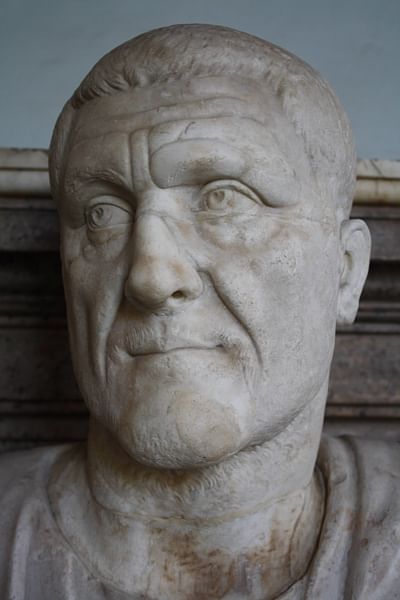

He followed his mother's advice to pay off his opponents for peace instead of engaging them in battle. While his mother regarded the option as the most prudent, Alexander's decision to follow her advice was seen as dishonorable and cowardly by Alexander's troops; he and his mother were both assassinated by his commanders. The Thracian soldier Maximinus Thrax (235-238 CE) then took control and became the first of the so-called “Barracks Emperors” who would come and go quickly throughout the crisis of the next 49 years.

The Barracks Emperors

The “Barracks Emperors” is a term coined by later historians referring to the Roman emperors who came from and were raised to power by the army. Whereas in the past an emperor came to power through a system of succession – either as the son or adopted heir of the sitting emperor – he was now chosen by the military based on his popularity with the troops, generosity toward the military, and his ability to produce immediate and discernible results. When any of these criteria were disappointed – especially the last – he was assassinated and replaced by another.

Between the reign of Alexander Severus and that of Diocletian, there were over 20 emperors who rose and fell in fairly swift succession. These were:

Maximinus Thrax (235-238 CE) who was killed by his troops when they tired of the constant warfare, foreign and domestic, he continued plunging them into. Further, he was considered an ineffective leader in the face of famine, plague, and large-scale civil unrest.

Gordian I and Gordian II (238 CE, March-April) were a father and son, made emperors by the Senate, who took part in the attempt to overthrow Maximinus. Gordian II was killed in battle fighting pro-Maximinus forces, and Gordian I committed suicide upon hearing of his death.

Balbinus and Pupienus (238 CE, April-July) also opposed Maximinus but were quite unpopular with the people and were killed by the Praetorian Guard.

Gordian III (238-244 CE) co-ruled with Balbinus and Pupienus until they were assassinated and was then proclaimed emperor by the military supporters of Gordian I and Gordian II. He was assassinated, probably by his successor Philip the Arab.

Philip the Arab (244-249 CE) was the Praetorian Prefect under Gordian III and made his son, Philip II, his co-emperor. He was killed in battle by his successor Decius, and his 12-year old son and co-emperor was then murdered by the Praetorian Guard.

Decius (249-251 CE) was a regional governor raised to power by his troops. He followed Philip's policy and made his son his co-emperor in order to ensure a smooth succession, but both were killed in battle fighting the Goth coalition under the leadership of King Cniva at the Battle of Abritus in 251 CE.

Hostilian (251 CE, June-November), the younger son of Decius, died in office from the plague.

Gallus (251-253 CE), a commander under Decius, also made his son, Volusianus, co-emperor; both were assassinated by their own troops who elevated Aemilianus.

Aemilianus (253 CE, August-October), a regional governor chosen by the troops, who proved disappointing and so was assassinated in favor of Valerian.

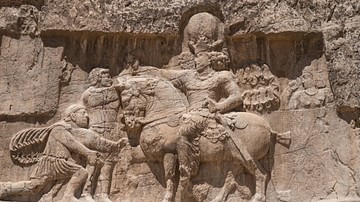

Valerian (253-260 CE) made his son Gallienus co-emperor. He was captured by the Sassanid Persians under Shapur I (240-270 CE) on campaign and died as their prisoner. According to some reports, his body was stuffed after his death and displayed in the Persian court for visiting dignitaries.

Gallienus (253-268 CE) was an effective ruler and military leader who initiated a number of important developments in the military (most notably expanding the role of the cavalry) and also culturally. Even so, he could not escape the climate of the times and was assassinated by his own troops on campaign in a conspiracy involving the future emperor Aurelian.

Claudius Gothicus (268-270 CE) who received his honorary epithet “Gothicus” following his victories over the Goths. He is said to have been reluctant to accept the position of emperor and avenged the murder of Gallienus. He showed great promise as an effective emperor but died of the plague only two years into his reign.

Quintillus (270 CE), the brother of Claudius Gothicus, came to power briefly following the latter's death but died soon after, probably assassinated by Aurelian.

Aurelian (270-275 CE) was one of the few Barracks Emperors to make a concerted effort to place the good of the people and security of the empire above his own personal ambition. He reunited the empire by defeating the Gallic and Palmyrene breakaway empires and bringing them back under Roman control and was also victorious over a number of different hostile tribes, thus securing the borders. In spite of his successes, he was assassinated by his commanders.

During the next nine years, Tacitus, Florianus, Probus, Carus, Numerian, and Carinus would rule – all following the same paradigm of elevation by the troops and, in most cases, assassination by them – until Diocletian took power. In the years all these men were fighting with each other over who would rule or should rule, the empire they sought to lead was falling apart. Since the death of Alexander Severus, the would-be emperors required larger and larger armies and more supplies and, lacking the funds to pay for these, they debased the currency again and again.

In response to the economic and social chaos of the time – and the uneven quality of leadership in dealing with a number of pressing difficulties – it is not surprising that the vast empire should split apart and leaders should arise who felt they could do better for their people without the drama and bloodshed that had become the government of Rome. In 260 CE the regional governor of Upper and Lower Germania, Postumus (260-269 CE), broke away to create the Gallic Empire comprised of Germania, Gaul, Hispania, and Britannia, and c. 270 CE Queen Zenobia of Palmyra (267-272 CE) in the east formed her own empire – the Palmyrene – which stretched from Syria down through Egypt.

The Breakaway Empires

Although Postumus and Zenobia are often characterized as rebels against Rome, they were not. There is nothing in Zenobia's official actions, and little in those of Postumus' after his initial strike, which could support a definition of “open rebellion” against the state as they were wise enough to recognize that, even with Rome's problems, it could still pose a substantial threat.

Instead of confronting Rome with a new potential enemy, Postumus assured the Roman Senate and the emperor that he was acting in Rome's best interest by securing the provinces and, in the east, Zenobia followed this same policy and even made sure to issue coinage with Aurelian's image on one side and her son Vaballathus's on the other. Zenobia seems to have hoped that her son would be considered for the dubious honor of becoming the next emperor of Rome and so the popular characterization of her empire as a rebellion is untenable. Postumus, although clearly acting on his own to the point where he created his own senate and government bureaucracy, also honored Rome in his policies and courted its favor.

Rather than open rebellions, the Gallic and Palmyrene empires should be regarded as natural and common-sense reactions to the chaos into which the Roman Empire had degenerated. Although it seems clear from a distance that both Postumus and Zenobia were vying for power and independent sovereignty of their realms, they did so at all times under the guise of acting on Rome's behalf and in the hope of some future reward or acknowledgement from the Roman government.

For most of the period of the Crisis of the Third Century the emperors were too busy fighting each other or driving off invading forces to pay much attention to the breakaway empires on their borders. When Aurelian came to power, however, he made the reunification of the empire a priority.

Aurelian's Restoration

Lucius Domitius Aurelianus – better known as Aurelian – was a commander of the cavalry under Gallienus and a popular and able leader. He was involved in the conspiracy to assassinate Gallienus, but before he could take power, Claudius Gothicus usurped the throne, and after his death, his brother Quintillus. Aurelian most likely disposed of Quintillus and was supported by the army in his coup.

He had already proven himself an exceptional and ruthless commander and between 270-272 CE elevated his reputation with campaigns against the Vandals, Alamanni, Juthungi, and Goths – among others – securing the borders of the empire. Once this was accomplished he turned his attention east and marched on Zenobia.

Aurelian was a soldier, not a politician, and so was uninterested in Zenobia's motives for taking Egypt nor in any of her actions which were allegedly done in service to Rome. Upon entering her territory, he implemented the same scorched earth policy which had worked so well against his other adversaries and destroyed every city he came to until he reached the outskirts of Tyana. This was the home-city of the famed philosopher and mystic Apollonius of Tyana, and in a dream, Apollonius appeared to Aurelian and told him to be merciful if he wished for victory. Aurelian spared the city, and word of his mercy spread quickly; the other cities in the region opened their gates to him without resistance upon his approach.

Zenobia assembled her armies under the command of her brilliant general Zabdas and met Aurelian at the Battle of Immae in 272 CE. Aurelian ordered his cavalry to engage and then retreat as though in a rout, forcing the opposing cavalry to pursue. Aurelian's strategy was to lure his opponents into a trap by tiring them out and leading them to a site of engagement of his own choosing, and this worked exactly as he had planned.

At a certain point, the Roman forces wheeled about and drove into the advancing Palmyrenes in a pincer movement which crippled their charge and killed most of them. Zenobia and Zabdas escaped the battle, regrouped, and fought again at the Battle of Emesa where Aurelian was again victorious using exactly the same strategy.

Zabdas was probably killed (he is not mentioned again), and Zenobia was taken prisoner by Aurelian. Although she is famously depicted as being paraded through the streets of Rome in golden chains, this is most likely a fiction. Aurelian would not have wanted to call any more attention to Zenobia than was necessary as it was already considered an embarrassment that he had to expend so much effort against a woman.

Once the regions of the east were restored to the empire, Aurelian marched west to subdue the area Postumus had claimed as his own. Postumus himself was dead by this time, killed by his own troops in 269 CE, and the Gallic Empire was led by Tetricus I (271-274 CE). Aurelian's reputation preceded him on his march west, and Tetricus I seems to have had little desire to meet the emperor on the field. Even so, the two armies met at the Battle of Chalons in 274 CE where Tetricus I's forces were nearly annihilated by Aurelian.

Much debate and speculation surround the Battle of Chalons since early reports claim that Tetricus I wrote to Aurelian before the event asking to surrender or, at least, for the emperor to spare him and his son. In the event, Tetricus I and his son were spared and Tetricus I lived out the rest of his life as an administrator, and this is seen by some as proof of Aurelian's later claims that Tetricus I betrayed his troops.

The claim makes little sense, however, as Aurelian would have been far better off sparing the entire army and simply accepting Tetricus I's surrender before battle. Although he won a decisive victory over Tetricus I, it still cost him in men and supplies, which were important resources in maintaining the empire. Further, he could have made ample use of the army Tetricus I fielded for the battle instead of slaughtering them.

A more likely reason for Tetricus I's survival is the lesson Aurelian learned on the Palmyra campaign regarding the benefit of mercy. In sparing Tetricus and his son, Aurelian showed himself a leader who did only what was necessary to restore order and who forgave, instead of punishing, transgressions.

It is probable that Aurelian thought this policy would work in his favor in the future, should any others decide to secede from the empire, but he did not live long enough to find out. He was assassinated by his commanders who were under the mistaken impression that he intended to execute and replace them.

Conclusion

The Imperial Crisis ended not so much with the restoration of the Roman Empire to what it had been as with a fundamental change in the most important aspects of government. Diocletian dealt firmly with every one of the aspects which had contributed to the chaos of the 50 years which preceded him. Building upon Aurelian's initiatives of securing the empire's borders and elevating the position of emperor above the common people or military, Diocletian went further in creating an aura of divinity around the position while reducing a ruler's reliance on military support.

He decreased the power of the military by implementing a policy of defense-in-depth whereby mobile forces within the empire would reinforce stationary forces garrisoned at the border, which meant he no longer needed large standing armies in forts who might become attached to their commander or regional governor. The mobile armies also took care of another problem: the propensity for soldiers to serve in their home regions. While this policy had been considered an advantage – as one would fight for one's home more resolutely than for a stranger's – it also allowed for greater bonds forged between the men and their regional commander than between the men and the emperor.

Diocletian also issued a more stable currency and curbed the rampant inflation and, to ensure a smooth succession and a more stable government, enacted the tetrarchy (rule of four) whereby the responsibilities of governing the vast empire were divided between two separate rulers whose successors were already in place when they assumed their positions. His final solution to the problems of the empire was his famous division of the realm between the Eastern and the Western Roman Empires, which made each more manageable under the reign of their respective emperors.

The efforts of Aurelian and Diocletian would sustain the Western Roman Empire for almost 200 years and the Eastern Roman Empire (known as the Byzantine Empire) until 1453 CE. The legacy of Rome, however, continues to the present day and has significantly affected generations of people around the world for centuries in a way it might not have if it had not survived its crisis in the 3rd century CE.