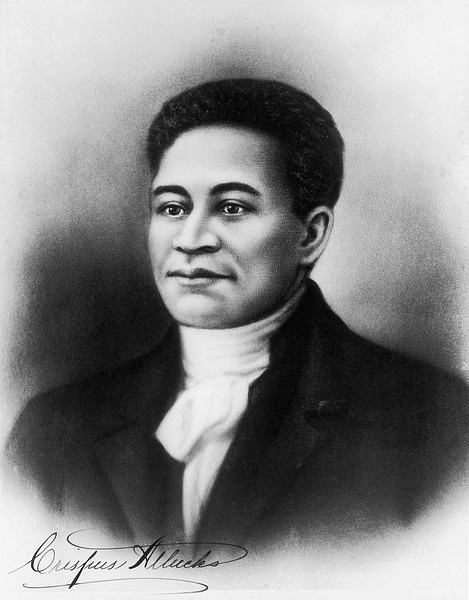

Crispus Attucks (l. c. 1723-1770) was an African American/Native American dockworker, sailor, and whaler who became famous as the first person killed in the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770, which raised tensions leading to the American Revolution (1765-1789). He is often referred to as a martyr in the cause of liberty.

It is unlikely, however, that Attucks joined the mob on the night of 5 March 1770 to advance the cause of upper-class White colonists to break away from British rule. It is far more likely he was protesting the pattern of British soldiers, garrisoned in Boston, taking jobs from lower-class people to supplement the poor pay of the British Army. The fact that he was the first person killed in the Boston Massacre does not make him a "martyr for liberty" any more than the other four killed that night.

The term "Boston Massacre" was coined by the Patriot colonist Samuel Adams (l. 1722-1803) as propaganda to advance the Patriot cause, and Attucks, whose race and social status were erased by Patriots such as Adams and Paul Revere (l. 1735-1818), became a convenient figure to become the first martyr of the American Revolution. Who he actually was and why he was on King Street that night is unknown.

Life & Ancestry Theories

Scholar Mitch Kachun notes:

There will likely never be a definitive biography of Crispus Attucks. Generations of scholars have probed the sources with only limited success in uncovering information about the man's actual life.

(2)

Prior to the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770 or, rather, to news reports of the event and the trial of the British soldiers involved later that year, Crispus Attucks' name was unknown. He may have been using the alias Michael Johnson while in Boston and is said to have come from Framingham, Massachusetts, which has linked him to a reward notice issued by one Deacon William Brown of Framingham in 1750 for the return of his escaped slave "Crispas."

Brown's notice describes a man matching Attucks' appearance and height, and the name "Crispas" is, of course, quite similar to "Crispus" so it is understandable that historians would claim that Attucks was the runaway slave, Crispas. This may not be so, however, nor is it clear that Attucks was using the alias Michael Johnson – it is possible that, after his death, he was confused with someone else of that name. He had to have been using his own name in order to be identified as Crispus Attucks shortly after the Boston Massacre.

The accepted 'biography' of his life, however, is that he was a former slave from Framingham of Native American (most likely Wampanoag) and African descent who had escaped and found work as a dockworker, sailor, and whaler and who may have arrived in Boston in early 1770 aboard a ship from the Bahamas and was scheduled to leave on another for North Carolina.

Attucks is described as over six feet tall (usually as 6 feet, 2 inches or c. 188 cm) and "stout", which was a term used for someone of strong build, and as a "mulatto" – a term used at that time to refer to Black slaves, Free Blacks, and Native Americans. Kachun and others have suggested he was a descendant of one John Attuck of Framingham who was hanged in 1676 for siding with the Wampanoag Confederacy against the colonists in King Philip's War (1675-1678).

As with the other attempts at tracing Attucks' lineage, there is no solid evidence for this connection. Historians writing on the subject tend to rely on words like "probable" or "possible" or "likely", but no documentation exists that firmly establishes a link between John Attuck and Crispus Attucks nor between one Nanny Peterattucks and Attucks nor between Attucks and any other person suggested as his mother, father, or other relative.

The claim that he was born in Framingham, Massachusetts, rests upon his identification with the runaway slave Crispas – which he may well have been – but this has never been firmly established. That being so, identifying Crispus Attucks with others of a similar surname from Framingham seems to be a mistaken endeavor.

As Framingham is not far from Boston, it seems unlikely a runaway slave from the one would take up residence in the other. There is also no evidence that Attucks was even a resident of Boston in 1770 since, as noted, accounts have him only recently arriving from the Bahamas and soon to leave for North Carolina. Most likely, he was a sailor who had found work at the docks of Boston in between jobs aboard vessels and that his involvement in the event that came to be known as the Boston Massacre had far more to do with British soldiers taking jobs away from dockhands (and other lower-class workers) than anything to do with the colonists' pursuit of independence from Great Britain.

Tensions in Colonial Boston

In 1770, tensions were high in the city of Boston as clashes between British soldiers and residents became more and more common. These soldiers were regarded by many as an occupying force but, at the same time, had made deep connections with the people of Boston. Scholar Serena Zabin writes:

Each soldier who took part in the massacre was just as much an individual as any of the others who had married a local woman, buried a child, or deserted from the army. To different degrees, each of these men had made connections in Boston. Some had made friends; others had made families.

(137)

Boston had been garrisoned by these troops in response to the colonists' objections to taxation. To help pay off the debt of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), the British Parliament decided to tax their thirteen colonies in North America, passing the Stamp Act in 1765, a tax on documents, which would pay for British troop deployments throughout the colonies.

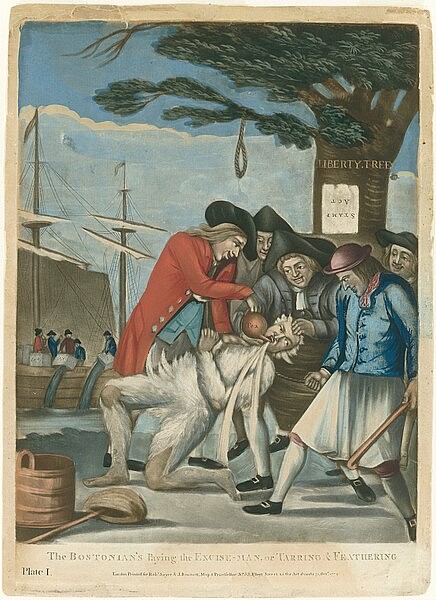

The colonists of Boston, objecting to "taxation without representation" in Parliament, responded by hanging in effigy one Andrew Oliver, the stamp distributor, and attacking the homes of British officials. The elm tree on which the effigy was hanged became Boston's famous Liberty Tree, which would later play a role in the Boston Massacre.

The colonists' response to the Stamp Act led to its repeal in March 1766, but between 1767 and 1768, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which taxed items such as glass, lead, paper, paint, and tea. The colonists reacted in the same way they had to the Stamp Act, but this time, Parliament was not going to back down. Approximately 2,000 British troops were deployed to Boston in 1768, and colonial authorities were told to provide them quarters – which they refused to do.

The soldiers then found quarters wherever they could – in private homes, inns, warehouses – and, when off-duty, found jobs to supplement their salary from the army. The soldiers were willing to work for less pay than the Bostonians, leading many to resent the 'redcoats' even more for taking jobs that, they felt, should have gone to citizens of Boston.

Those who identified as Patriots – advocating for a break from Great Britain - boycotted the Townshend Acts and encouraged others to do the same. A merchant named Theophilus Lillie objected to the boycotts and observed the strictures of the Townshend Acts, eventually leading to a mob gathering outside his shop in protest on 22 February 1770.

His neighbor, Ebenezer Richardson, intervened but was driven off. The mob followed him to his house, where Richardson, fearing for his life, fired into the crowd, killing an eleven-year-old boy named Christopher Seider. As Richardson was a known Loyalist to Great Britain, his shooting of Seider encouraged further resentment against the crown, especially after Richardson, convicted of murder, was pardoned by King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820).

The Boston Massacre

Tensions escalated further, as Zabin explains:

Early in March 1770, one rope maker [John Gray] offered a soldier work requiring no particular skill: cleaning his latrine. The soldier was offended at what he took to be fighting words, and a quarrel escalated over the next several days, as each side brought more friends into the fray.

(148)

According to the PBS site Africans in America:

A fight between soldiers and ropemakers on Friday, March 2, 1770, ignited a series of confrontations that led to the Boston Massacre the following Monday. Crispus Attucks, a mulatto sailor, ropemaker and runaway, and the first to be killed, was one of a number of seamen and dock workers present [at the massacre].

(1)

Attucks may also have been present at the fight at John Gray's Ropewalk or those that continued over the next few days. British soldiers had already taken jobs from dockworkers, and now, it seemed, they were trying to take positions as rope-makers. Jobs were already scarce, and few were open to members of the free Black community of Boston. Attucks, then, may have been joining fellow dockworkers in giving the British notice they were not welcome in these occupations.

On the night of 5 March 1770, Private Hugh White of the 29th Regiment was standing guard duty outside the customshouse on King Street when he overheard a colonist, one Edward Gerrish, insult British army officers and struck him. According to Kachun:

When a sentry rifle-butted a young wigmaker's apprentice after the boy insulted an officer of the Fourteenth regiment, townsmen rallied. Ringing church bells – normally an alarm for fire – brought scores more people into the streets. By around 9:00 in the evening, a group of about twenty to thirty teenage boys and young men gathered around the offending sentry, Hugh White, and began pelting him with insults, snowballs, and chunks of ice. White loaded his rifle, retreated to the door of the King Street Custom House, and called for the main guard…Rumors of British violence circulated as church bells continued to pull people into the streets.

(13)

According to Zabin and others, there was already commotion in the streets, though not King Street, before White struck Gerrish (Zabin, 139). A rumor seems to have circulated that the British were planning on cutting down the Liberty Tree, and some Bostonians were already out to prevent that. Zabin suggests the shouts and cries heard by Private White and a woman he was speaking with, one Jane Crothers, may have been "crowds of sailors, led by a tall mixed-race man later identified as Crispus Attucks" (153). If Zabin is correct, Attucks may have been leading dockworkers to confront British troops over what they saw as the theft of jobs.

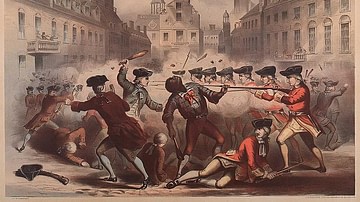

In response to White's call for help, Captain Thomas Preston ordered six privates and a corporal to follow him and marched up King Street. The tolling of the city's bells brought more people into the street, many carrying buckets, thinking they were responding to a fire. Preston's company and Private White were pushed by the mob back against the customshouse, where Preston organized them in a semicircle. According to some, though not all, reports, the soldiers were then pelted with snowballs, chunks of ice, pieces of wood, and sticks.

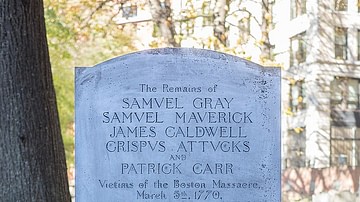

When an ice chunk struck Private Hugh Montgomery, he fell, rose, and fired into the crowd; then the other soldiers discharged their muskets. Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, and James Caldwell were killed instantly. Samuel Maverick was mortally wounded and died the next morning. Patrick Carr, also mortally wounded, died two weeks later. Six others were wounded, but not seriously. The shots dispersed the crowd, and the next day, Captain Preston and his men were arrested. They were defended at trial months later by John Adams (l. 1735-1826), the future second president of the United States, and all acquitted save two, who were convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter and sent home to England.

Attucks' Role

Precisely what role Crispus Attucks played in the events of 5 March 1770 is unknown. At the trial, some people claimed he was the leader of the mob, some that he was simply part of it, and some had no recollection of him at all. Zabin writes:

Only three of fifty-one witnesses mentioned seeing a "mulatto" or mixed-race man, before the shooting; one thought he had noticed that Attucks was dressed as a sailor. The same witness also testified that Attucks had handed him a club and then walked down Crooked Lane to the corner of King Street, where he "went on cursing and swearing at the soldiers." A few of the prosecution's witnesses had also spotted Attucks, although most of them did not claim that he was particularly aggressive. One observed him silently resting his weight on a stick; the other affirmed that Attucks neither spoke to the soldiers nor threw anything at them.

Only one witness, James Bailey, who had spoken earlier and not too effectively for the prosecution, gave a different picture of Crispus Attucks. He told the court that he had seen Attucks "at the Head of 25 or 30 sailors," some of whom had clubs.

(214)

John Adams, in his defense of the British soldiers, seized on Bailey's testimony and characterized Attucks as the leader of the mob:

To have this reinforcement coming down under the command of a stout Mulatto fellow, whose very looks was enough to terrify any person, what had not the soldiers to fear? This is the behavior of Attucks – to whose mad behavior, in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night is chiefly to be ascribed.

(MA Historical Society History Source)

This does not mean, however, that Attucks was the leader of the mob that night. The characterization of Attucks as leader was simply a legal maneuver of Adams to cast Attucks as an outsider, a runaway slave who had come as a fugitive to Boston – who was not, then, one of the peoples' own – and as a troublemaker. In Adams' characterization, the "good people of Boston" had been led astray by Attucks, and the British soldiers had fired on the crowd in simple self-defense.

Only Bailey's testimony claims Attucks led a mob that night, and, as noted, many people claimed they did not remember seeing him at all. As a defense attorney, Adams turned Bailey's testimony to his own advantage in villainizing Attucks, but, as a Patriot, he seems to have admired the man. Paul Revere, one of the most famous Patriots of the era, made an engraving of the Boston Massacre depicting Attucks at the front of the crowd, but making him a White Bostonian.

Samuel Adams (John's second cousin) and the other Patriots did the same, proclaiming Attucks a martyr, along with the other four, in the cause of liberty. The five martyrs of the Boston Massacre were buried together in the Granary Burying Ground, and the event and those who fell in the fight for liberty were regularly celebrated throughout the American Revolutionary War.

Conclusion

In time, however, Crispus Attucks faded from memory. After 1783, the Boston Massacre was celebrated less and less, especially after the 4th of July became recognized as the birth date of the United States of America. During the 19th century, however, abolitionists revived the memory of Attucks as "First Martyr of Liberty" in an effort to include an African American as a foundational figure of the Revolutionary era. Kachun writes:

By the 1840s, a handful of black activists became aware of Crispus Attucks, his racial identity, and his actions in 1770. As they went about constructing a story asserting blacks' rightful place in the nation, African American activists recognized the central role Attucks might play and began the process of reinscribing him into the history of the American Revolution and the pantheon of American patriot heroes.

(45)

This trend continued into the 20th century when fictionalized history books, children's books, and comic books – especially of the 1960s and early 1970s – began to depict Attucks as a Patriot revolutionary and leader of a mob that attacked a group of British soldiers to win liberty for the colonies of North America.

It is entirely possible that Crispus Attucks was, indeed, that figure, but it is far more likely he was a dockworker trying to protect his job and those of his friends, who, after being whitewashed by the Patriots of the Sons of Liberty, was transformed into a martyr for their cause.