Cynisca of Sparta (b. c. 440 BCE) was a Spartan royal princess who became the first female Olympic champion. Defying the traditional role of women in ancient Greece, she competed in the Olympic Games alongside the men and won. Her triumph in Greek athletics became a symbol of inspiration for women of future generations and her legacy is still remembered today.

Women’s Status in Sparta & Other Greek City-states

It has been a longstanding axiom that a woman’s place in Ancient Greece was in the home. There, her duties would be "tending the hearth and supervising domestic activities, while men concentrated on the more important affairs of politics, theater, athletics, and the like" (Miller, 150). Generally speaking, in Greek society, women were deemed inferior. The Greek philosopher Aristotle said, "he could prove scientifically that women’s bodies and women’s minds…were categorically, naturally, that is unalterably, inferior to men’s" (Cartledge, 166). Aristotle further adds that they were "deformed males" and intellectually lacked the ability to reason (Cartledge, 166-167).

Despite this, Spartan women proved to be strong and disproved the famous philosopher. Women in Sparta enjoyed greater freedom than in any other ancient Greek city. Spartan women were entitled to manage and own property in their own right, without a male guardian. In Athens, women were the mere vehicles for producing male heirs to inherit the households while in Sparta these women could inherit in their own right. Spartan women were also granted certain freedoms that were considered lax to other city-states. Spartan wives were also granted freedom to maintain extramarital relationships without violating any adultery laws because there were no such laws in Sparta, unlike the rest of Greece. They also did not have to cook or prepare food, do housework or make clothes, and presumably, they had no obligation to breastfeed children. All these duties were carried out by Helot women.

Physical Education of Spartan Women

There is more textual and archaeological evidence for Spartan women in athletics than any other aspect of their lives. In fact, there is more evidence for athletics for women in Sparta than women in the rest of the Greek world combined. This aspect caught the attention of many Greek writers, who found Spartan women in athletics to be very unique. Xenophon (430 - c. 354 BCE) recounts that Lycurgus (9th century BCE) instituted the agoge, the Spartan education program, which included "physical training for women no less than for men, including competitions in racing and trials of strength" (Pomeroy, 12-13). Greek tragedy playwright Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE) refers to wrestling and racing, while Plutarch (45/50-120/125 CE) gives a more explicit account regarding the curriculum and mentions wrestling, running, javelin hurling, and discus throwing. While these were useful skills for a soldier, Spartan women nonetheless took part in these activities. For women, these physical activities were less arduous and selective compared to the men’s version, but nearly similar.

Sarah Pomeroy states, "Spartan women were not trained for actual combat" (16). It was not clear if they engaged in co-ed athletics with men, but Pomeroy argued if they were, they would have been further prepared. Philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato argued that they were no different than other Greek women. When Epaminondas invaded Sparta with his Theban army in 369 BCE, the women fled in terror. Plutarch argued that the purpose of their physical education was to defend themselves, their children, and their country.

The Olympic Games

The rules for participating in the Olympic Games were very strict and generally did not favor women. It was seen as a male-exclusive arena, and women were generally seen participating in domestic activities at the home. However, stereotypes of women and their place in athletics are not unequivocal as they seem. Our evidence for this is very fragmentary and slight compared to the information covering men’s athletics. However, it is clear women also participated in athletics and "were an important part of the athletic picture even if their competitions never approached an equal footing with men’s" (Miller, 152-153). Cynisca is a perfect example of this.

According to Pausanias (c. 510 - c. 465 BCE), parthenoi, or virgin/unmarried women, could view the games, but married women were excluded. However, this could be unlikely if there was a need for young girls to be chaperoned. It is possible that fathers accompanied their daughters to the games. Sarah Pomeroy states Pausanias may be thinking of the parthenoi who were present "not because they were spectators, but because they participated in the races at Elis" (Pomeroy, 22). An exception was granted to the priestesses of Demeter, who sat at the altar to the goddess during the games.

Equestrian affairs were an arena of excellence in Sparta. "Women as well as men were actively involved with horses, riding, driving horse-drawn vehicles, and engaging in competitive equestrian events" (Pomeroy, 19). Women seemed to understand horses well. At the Hyacinthia, Spartan girls "drove expensively decorated light carts, and had an opportunity to display their equestrian skills before the entire community. Some raced in chariots drawn by a yoke of horses" (Pomeroy, 20). This skill for Spartan women made Cynisca the perfect candidate to enter the Olympic Games. However, it is important to note that it was not her idea to compete in the four-horse chariot race, but it was that of her brother, Agesilaus. According to Paul Cartledge, Agesilaus’ aim "was to demonstrate that victories won in this way were a function merely of wealth, unlike victories in other events and spheres (above all battle) where what counted decisively was manly virtue" (Cartledge, 215).

Cynisca

The name Cynisca literally means "female puppy" and may sound like a childhood nickname, maybe synonymous with a tomboyish girl. Her paternal grandfather was Zeuxidemus and was nicknamed Cyniscus, which was the masculine form of Cynisca. Nevertheless, the latter was the name given to the first female Olympic champion. Cynisca was the sister of the Spartan King Agesilaus II and daughter of King Archidamus II and Eupolia, born around 440 BCE. She was considered a Spartan royal princess and no ordinary Spartan girl.

According to Plutarch, King Agesilaus noticed some Greek "citizens took pride in breeding racehorses and gave themselves great airs in consequence, and so he persuaded his sister Cynisca to enter a chariot-team at the Olympic Games" (Plutarch, 58). Cynisca entered her horses as early as possible and won in two successive Olympiads in 396 and 392 BCE. According to Pausanias, Cynisca had longed to succeed in the Olympic Games and became the first woman to not only win in the Olympic Games but also to own racehorses. Her quadriga (four-horse chariot) was a testament to great wealth like that of her contemporaries who were also deemed victors, including tyrants from Sicily. "Likewise, Cynisca’s commemorative monuments were examples of conspicuous consumption equal to those of men" (Pomeroy, 22). Cynisca, like wealthy male racehorse owners, did not drive them herself but employed a jockey. Women were not permitted to attend the games, therefore she was not present at the triumphant event.

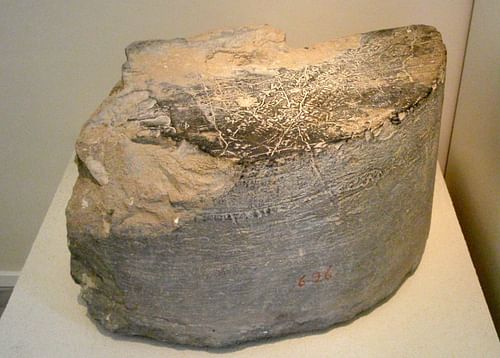

Cynisca’s image stood in a sanctuary. Apelles of Megara designed a sculpture of her chariot, horses, and charioteer in bronze as well as a statue of Cynisca herself. These statues were erected at Olympia. "They were the first monuments dedicated by a woman to commemorate victories at pan-Hellenic competitions" (Pomeroy, 22).

Cynisca’s Epigram

The author of Cynisca’s epigram remains unknown. According to Sarah Pomeroy, "the poem is metrically competent; straightforward in the ‘Laconic’ style; and of course written in the Doric dialect" (Pomeroy, 22). Cynisca herself is represented speaking the words:

My ancestors and brothers were kings of Sparta.

I, Cynisca, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses,

erected this statue. I declare that I am the only woman

in all of Greece to have won this crown. (Pomeroy, 22)

Legacy

Cynisca’s commemorative sculptures at Elis stood between the statues of male Lacedemonians and Troilus of Elis. After her death, she was posthumously awarded a heroine’s shrine in Sparta and was religiously venerated thereafter. This complemented her lifetime monument erected at Olympia. The hero shrine stood near the Platanistas. This was where the athletic contests of young Spartans took place. In Greece, it was common for athletes to be elevated to hero status, and Cynisca became the first woman to be treated as such. Pomeroy notes, "Her shrine was in the vicinity of the shrines of mythical heroes including the sons of Hippocoon. The heroon would have been built after her death and would have served as an inspiration to other women" (23).

Other women, especially Spartans, followed her example, and Pausanias records this as a trend. Some managed to win Olympic victories, but none was more famous than her. One example was the Spartan woman Euryleonis, who won with a two-horse chariot at Olympia in 368 BCE. A statue of her stood with those of other achievers in the vicinity of a bronze house. Cynisca and Euryleonis are remembered as the first women who were victorious in chariot races at Olympia. Nearly a century later they were followed by common and royal women connected to the courts of Alexander the Great’s successors.

Other women also won victories in hippikos agon or horse racing. In 47 CE, a man named Hermesianax made a dedication on behalf of his daughters at Delphi: Tryphosa who won in foot racing at the Pythian and Isthmian games, Hedea who excelled in chariot racing "in armor at the Isthmian Games," and Dionysia who won in the Isthmian Games (Miller, 154). Scholars have debated if Hedea and Dionysia were in male competitions or special girls’ categories. However, all have taken these records as anomalies of the Roman period.

Although our sources are fragmentary regarding women’s participation, it is clear that they excelled in athletic events, especially in Sparta. In this sense, women were not always confined to the domestic sphere and entered a once strictly male sphere. Indeed Cynisca’s legacy set an example for women in generations to come. In a time where athletics had been considered a predominantly male arena, she proved women can excel in the Olympic Games as well.