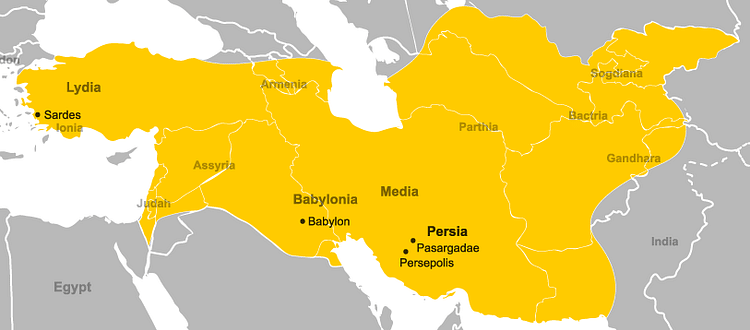

Cyrus II (d. 530 BCE), also known as Cyrus the Great, was the fourth king of Anshan and the first king of the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus led several military campaigns against the most powerful kingdoms of the time, including Media, Lydia, and Babylonia. Through these campaigns, he united much of the Middle East under Persian hegemony while keeping the local administration mostly intact. By guaranteeing some continuity and thus winning the loyalty of the elite, he laid the foundations for the Achaemenid Empire.

EARLY LIFE

Not much is known about the early life of Cyrus. The various oral traditions relating to his birth and youth are preserved only in the works of Greek authors like Herodotus, Ctesias, and Xenophon, who present contradictory accounts of a mostly legendary nature. According to the most well-known account of Herodotus, Cyrus was the son of the Persian king Cambyses (c. 580-559 BCE) and the Median princess Mandane, daughter of the Median king Astyages (585-550 BCE). Ctesias explicitly contradicts Herodotus, however, claiming instead that Cyrus was the son of a Persian brigand named Artadates and his wife, the goatherd Argoste. According to Ctesias, Cyrus served at Astyages' court as a chief cupbearer before overthrowing him. After his coup, Cyrus adopted Astyages as his father and married his daughter Amytis.

According to contemporary Achaemenid inscriptions, like the Cyrus Cylinder and the Behistun Inscription, Cyrus was king of Anshan (a kingdom in Fars with a mixed Elamite and Persian population) and a son of Cambyses. However, it must be noted that the Achaemenids inscriptions never mention any genetic relation between Cyrus and Astyages. Although intermarriage between Iranian royal families is certainly a possibility, it is also possible that Cyrus only claimed to be Astyages' grandson in order to gain legitimacy (as per Herodotus) and that he married Astyages' daughter Amytis for the same reason (as per Ctesias). Finally, Herodotus, Ctesias, and Xenophon all agree that Cyrus spent part of his youth at Astyages' court. This may be based on historical truth, but, again, this may also simply be a legendary motif.

CONQUEST OF ECBATANA

Cyrus' first great achievement was his conquest of Ecbatana, the Median capital ruled by Astyages. This event is first mentioned in two contemporary Babylonian sources: the Nabonidus Cylinder of Sippar and the Nabonidus Chronicle. Herodotus also gives us a detailed account of this event. According to the Nabonidus Cylinder of Sippar, Cyrus, king of Anshan, rose up against his overlord, the Median king Astyages, in 553 BCE. After defeating the "vast Median hordes" with his "small army", he captured Astyages and brought him back to his homeland. The Nabonidus Chronicle states instead that Astyages marched on Cyrus in 550 BCE, but his army rebelled against him, took him captive and handed him over to Cyrus. Cyrus then took Ecbatana and carried off the spoils. The discrepancy in dates between these two sources may be explained by assuming that Cyrus started his rebellion in 553 BCE, that Astyages marched against Cyrus in 550 BCE and that the revolt in the Median army happened during that campaign.

Herodotus' account agrees with the Nabonidus Chronicle up to a great degree. Herodotus states that Harpagus, a Median nobleman, encouraged Cyrus to rise up against Astyages, who had wronged him in the past. Harpagus sought support from among the other Median nobles, who were also unhappy with Astyages' rule. Astyages, upon hearing about Cyrus' rebellion, appointed the same Harpagus to lead the Median army against Cyrus. When the Median and Persian armies met, Harpagus and the other noblemen crossed over to Cyrus as planned. All sources agree that Cyrus spared Astyages' life. If we are to believe Ctesias, Cyrus even adopted Astyages as his father and married his daughter Amytis, presenting himself as the rightful successor of Astyages as king of the Medes. It is often assumed that Cyrus took over all the lands that had been conquered by the Medes, which according to Herodotus encompassed all of Asia except for Assyria, however, recent research concludes that the territory of the Medes was much smaller or even that there was no Median Empire at all. Still, it seems likely that Cyrus' power and prestige on the Iranian Plateau increased greatly after this victory.

BUILDING OF PASARGADAE

After his victory over Astyages, Cyrus founded the city of Pasargadae on the site of the battle. Pasargadae served as a ceremonial capital of the early Achaemenid Empire and was never meant to house a large population. The city consists of several monumental buildings spread out across the Murghab plain, most notably the Tall-e Takht (a stone citadel on top of a steep hill), Palace P (a residential building), Palace S (a columned audience hall) and finally the tombs of Cyrus and his son Cambyses.

The monuments of Pasargadae contain influences from across the known world, including Assyrian style sculptures and Ionian style masonry. The Tomb of Cyrus is thought to represent a Mesopotamian or Elamite ziggurat with an Urartaean style cella on top. Pasargadae flourished only for a short time, with Persepolis taking over its role as the ceremonial capital in 515 BCE.

CONQUEST OF LYDIA

Cyrus conquered Lydia sometime between the fall of Ecbatana (550 BCE) and the fall of Babylon (539 BCE). The Nabonidus Chronicle states that Cyrus led a campaign west of the Tigris in 547 BCE, however, most scholars now agree that this campaign had a different target. Herodotus claims that it was Croesus (560-547 BCE), king of Lydia, who started the war by crossing the Halys River and sacking Pteria, a Cappadocian city within the Median sphere of influence. Croesus was an ally and brother-in-law to Astyages, so upon hearing that Cyrus had deposed Astyages, he swore to avenge him. The two armies met near Pteria, but the battle ended in a stalemate. When Croesus decided to march his army home for the winter season, Cyrus pursued him into Lydia and confronted him a second time near Thymbra. Cyrus deployed dromedaries to disperse the Lydian cavalry forcing Croesus to retreat into his capital city of Sardis, which fell after a 14-day siege.

There is some discussion as to what happened to Croesus after his final defeat. Herodotus, Ctesias, and Xenophon all agree that Cyrus threatened to punish Croesus first, but that he took pity on him and even appointed him as his personal advisor. So far, it seems plausible that Croesus survived the fall of Sardis. Some scholars, however, consider such accounts to be legendary and believe that Cyrus did indeed execute Croesus. After the fall of Sardis, Cyrus put a Lydian named Pactyes in charge of Croesus' treasury. Pactyes' job was to send these treasures to Persia, but, instead, he organised a revolt, hiring mercenaries. Cyrus' sent his general Mazares to quell the rebellion, but due to his untimely death, it was Harpagus who completed the conquest of Asia Minor, capturing the cities of Lycia, Cilicia, and Phoenicia by building earthworks.

OTHER CAMPAIGNS

Sometime in the 540s BCE, Cyrus must have conquered the Bactrians and the Sacae. According to Ctesias, when the Bactrians heard that Cyrus had treated Astyages with respect, they voluntarily submitted to them, implying that the Bactrians had been either subjects or allies to Astyages. After strengthening his influence over the eastern part of the Iranian Plateau, Cyrus turned his attention to the nomadic Sacae. He captured their king Amorges, but Amorges' wife Sparethra gathered an army of 300,000 men and 200,000 women and defeated Cyrus in battle. Cyrus released Amorges and the two kings became allies, attacking Lydia together. If this account is true, Cyrus may have conquered the Bactrians and the Sacae before conquering Lydia. Finally, Cyrus must have conquered the region of Armenia in the mid-6th century BCE, possibly installing his ally Tigranes Orontid as king of Armenia.

CONQUEST OF BABYLON

In 539 BCE Cyrus invaded the Babylonian Empire, following the banks of the Gyndes (Diyala) on his way to Babylon. He allegedly dug canals to divert the river's stream, making it easier to cross. Cyrus met and routed the Babylonian army in battle near Opis, where the Diyala flows into the Tigris. After this, the people of Sippar opened their gates to him without resistance. The Babylonian king Nabonidus fled, and Cyrus sent his servant Ugbaru, the governor of Gutium, to capture Babylon. Ugbaru captured the outer neighbourhoods of Babylon, with only the temple district of Esagil remaining under Babylonian control. After two weeks, Cyrus was welcomed into Babylon with festivities.

With Babylon under Persian control, Cyrus could add the title 'king of Babylon' to his name. He inherited all the territories that had belonged to the Babylonian Empire, and he apparently had no trouble pacifying these regions. In fact, Harpagus may already have conquered much of the Mediterranean coast before Cyrus attacked Babylon. Cyrus now ruled over the fertile river valleys of Mesopotamia, in addition to the rich Mediterranean coast.

CYRUS CYLINDER

Not long after the conquest of Babylon, Cyrus commissioned a building inscription to be written in his name. This building inscription, better known as the Cyrus Cylinder, served to explain and justify Cyrus' conquest of Babylon to a Babylonian audience. The document appeals heavily to the Babylonian ideals of kingship. Nabonidus is described as an incompetent, godless king, while Cyrus is described as a divinely appointed saviour.

The Cyrus Cylinder starts off by claiming that Nabonidus neglected the cult of Marduk, the patron god of Babylon. Nabonidus did indeed prefer the moon god Sîn over the national god Marduk, so there may be some truth to this. Still, it is likely that the neglect of the cult of Marduk was strongly exaggerated. Nabonidus also imposed heavy labour on his people, perhaps in preparation for the Persian invasion. Marduk, feeling pity for the people of Babylon, searches all the lands for a truly righteous king, eventually choosing Cyrus of Anshan. Marduk leads Cyrus to victory against the Medes and helps him capture Babylon without a battle.

Cyrus then introduces himself first as a king of Babylon, a king of Anshan, a descendant of Teispes, and a favourite of Marduk. Cyrus claims that he has not pillaged the city, that he has not frightened anyone, that he had worshipped Marduk daily, and that he had freed the people of Babylon from the heavy labour that Nabonidus had imposed on them. Cyrus also claims to have returned the idols, that Nabonidus had brought to Babylon from temples all across Mesopotamia, back to their temples, along with their temple personnel. Cyrus finishes his speech with a prayer to Marduk and a description of his building activities.

RELIGION OF CYRUS

Although it is often assumed that Cyrus was a Zoroastrian, there are no contemporary sources that describe him as a follower of Zarathustra of even a worshipper of Ahura Mazda. In fact, Zoroastrianism, as we know it today, may not even have existed during his lifetime. The beliefs and practices associated with Zoroastrianism were not standardized until the late Sasanian period. Before that time there was no orthodoxy and the Iranians adhered to a wide array of loosely associated beliefs and practices. Ahura Mazda was just one among many Iranian gods and Zarathustra was just one prophet who happened to favour Ahura Mazda over all the others. Taking this into account, it is likely that Cyrus was a polytheist who grew up worshipping the traditional Iranian gods. Xenophon describes him as swearing an oath to Mithra, the Iranian god of oaths, but he may have turned to other gods for other purposes. It should therefore not surprise us that Cyrus offers sacrifice to the Babylonian gods Marduk and Nabu. This was his way of placating the gods of the lands that he conquered.

DEATH

As with his birth and youth, not much is known about the last nine years of Cyrus' life. Herodotus claims that Cyrus died fighting the Massagetae, a nomadic people who lived across the Iaxartes. Queen Tomyris of the Massagetae allegedly beheaded Cyrus in order to avenge the death of her son at his hands. Ctesias claims instead that Cyrus died trying to put down a revolt of the Derbices, another nomadic people from Central Asia, while Berossus claims that Cyrus died fighting the Dahae nomads. It is likely that Cyrus did indeed die in Central Asia while trying to expand his influence over the region. From Babylonian letters, it is known that Cyrus died before December 530 BCE. He was buried in his tomb in Pasargadae, along with his cloak, his weapons and his jewels. Upon his death, Cyrus was succeeded by his son Cambyses II.

LEGACY

Between the beginning of his revolt against Astyages in 553 BCE and his death in 530 BCE, Cyrus united all the lands between the Aegean Sea and the Iaxartes under his rule. By means of several swift campaigns, he dethroned many powerful kings, either appointing Persian satraps in their stead or claiming the title of 'king' for himself. This way he established Persian dominance over the entire Middle East. Upon conquering a kingdom, Cyrus usually allowed the local officials to maintain their position. This way, the administrative infrastructure remained intact. He also accommodated the cultural and religious practice of the lands that he conquered, thus winning the respect of his subjects and securing the loyalty of the traditional elites in the kingdoms he conquered, such as the Median nobility and the Babylonian priesthood.