D-Day was the first day of Operation Overlord, the Allied attack on German-occupied Western Europe, which began on the beaches of Normandy, France, on 6 June 1944. Primarily US, British, and Canadian troops, with naval and air support, attacked five beaches, landing some 135,000 men in a day widely considered to have changed history.

Where to Attack?

Operation Overlord, which sought to attack occupied Europe starting with an amphibious landing in northwest France, Belgium, or the Netherlands, had been in the planning since January 1943 when Allied leaders agreed to the build-up of British and US troops in Britain. The Allies were unsure where exactly to land, but the requirements were simple: as short a sea crossing as possible and within range of Allied fighter cover. A third requirement was to have a major port nearby, which could be captured and used to land further troops and equipment. The best fit seemed to be Normandy with its flat beaches and port of Cherbourg.

The Atlantic Wall

The leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), called his western line of defences the Atlantic Wall. It had gaps but presented an impressive string of fortifications along the coast from Spain to the Netherlands. Construction of gun batteries, bunker networks, and observation posts began as early as 1942.

The German high command knew an attack would come but not where. The Allies spent much effort with diversionary intelligence to make the enemy think the invasion was going to happen anywhere except Normandy. The favourite that turned out to be quite wrong was the deception that Calais would be the landing area. Many German commanders thought the Pas de Calais the most obvious choice since it was the closest to Britain. Accordingly, this area was the best defended. The Allies took advantage of another of the enemy's convictions, this time that the American general George Patton (1885-1945), known for his aggressive tactics, would command the D-Day assault. The Allies used Patton and an entirely fictitious army group as a red herring. Even when D-Day began, the German commanders were not sure that Normandy was not being subjected to a diversionary attack while the real invasion was happening elsewhere. To keep the plan and build-up of troops secret, no one was allowed to leave Britain without authorisation, including diplomats.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953), commander-in-chief of the German army in the West, believed it would be impossible to stop an invasion on the coast and so it would be better to hold the bulk of the defensive forces as a mobile reserve to counterattack against enemy beachheads. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), commander of Army Group B, disagreed and considered it essential to halt any invasion on the beaches themselves. Further, Rommel believed that Allied air superiority meant that movements of reserves would be severely hampered. Hitler agreed with Rommel, and so the defenders were strung out wherever the fortifications were at their weakest. Rommel improved the static defences and added steel anti-tank structures to all the larger beaches. In the end, Rundstedt was given a mobile reserve, but the compromise weakened both plans of defence. The German armed forces were not helped either by their confused command structure, which meant that Rundstedt could not call on any armour (but Rommel, who reported directly to Hitler, could), and neither commander had any control over the naval and air forces available or the separately controlled coastal batteries. Nevertheless, the defences were bulked up around the weaker defences of Normandy to an impressive 31 infantry divisions plus 10 armoured divisions and 7 reserve infantry divisions. The German army had another 13 divisions in other areas of France. A standard German division had a full strength of 15,000 men.

Many of the German divisions were not crack troops but inexperienced soldiers, who were spending more time building defences than in vital military training. There was a woeful lack of materials for Hitler's dream of the Atlantic Wall, really something of a Swiss cheese, with some strong areas, but many holes. The German army was not provided with sufficient mines, explosives, concrete, or labourers to better protect the coastline. At least one-third of gun positions still had no casement protection. Many installations were not bomb-proof. Another serious weakness was naval and air support. The navy had a mere 4 destroyers available and 39 E-boats while the Luftwaffe's (German Air Force's) contribution was equally paltry with only 319 planes operating in the skies when the invasion took place (rising to 1,000) in the second week.

Neptune to Normandy

The Supreme Commander of the Allied invasion force was General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969), who had been in charge of the Allied operations in the Mediterranean. The commander-in-chief of the Normandy land forces, 39 divisions in all, was the experienced General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976). Commanding the air element was Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh Mallory (1892-1944) with the naval element commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945).

Preparation for Overlord occurred right through April and May of 1944 when the Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Air Force (USAAF) relentlessly bombed communications and transportation systems in France as well as coastal defences, airfields, industrial targets, and military installations. In total, over 200,000 missions were conducted to weaken as much as possible the Nazi defences ready for the infantry troops about to be involved in the largest troop movement in history. The French Resistance also played their part in preparing the way by blowing up train lines and communication systems that would ensure the defenders could not effectively respond to the invasion.

The Allied fleet of 7,000 vessels of all kinds departed from English south-coast ports such as Falmouth, Plymouth, Poole, Portsmouth, Newhaven, and Harwich. In an operation code-named Neptune, the ships gathered off Portsmouth in a zone called 'Piccadilly Circus' after the busy London road junction, and then made their way to Normandy and the assault areas. At the same time, gliders and planes flew to the Cherbourg peninsula in the west and Ouistreham on the eastern edge of the planned landing. Paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st US Airborne Division attacked in the west to try and cut off Cherbourg. At the eastern extremity of the operation, paratroopers of the 6th British Airborne Division aimed to secure Pegasus Bridge over the Caen Canal. Other tasks of the paratrooper and glider units were to destroy bridges to impede the enemy, hold others necessary for the invasion to progress, destroy gun emplacements, secure the beach exits, and protect the invasion's flanks.

The Beaches

The amphibious attack was set for dawn on 5 June, daylight being a requirement for the necessary air and naval support. Bad weather led to a postponement of 24 hours. Shortly after midnight, the first waves of 23,000 British and American paratroopers landed in France. US paratroopers who dropped near Ste-Mère-Église ensured this was the first French town to be liberated. From 3.00 a.m., air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast began, letting up just 15 minutes before the first infantry troops landed on the beaches at 6.30 a.m.

The beaches selected for the landings were divided into zones, each given a code name. US troops attacked two, the British army another two, and the Canadian force the fifth. These beaches and the troops assigned to them were (west to east):

- Utah Beach - 4th US Infantry Division, 7th US Corps (1st US Army commanded by Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley)

- Omaha Beach - 1st US Infantry Division, 5th US Corps (1st US Army)

- Gold Beach - 50th British Infantry Division, 30th British Corps (2nd British Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Miles C. Dempsey)

- Juno Beach - 3rd Canadian Infantry Division (2nd British Army)

- Sword Beach - 3rd British Infantry Division, 1st British Corps (2nd British Army)

In addition, the 2nd US Rangers were to attack the well-defended Pointe du Hoc between Utah and Omaha (although it turned out the guns had never been installed there), while Royal Marine Commando units attacked targets on Gold, Juno, and Sword.

The RAF and USAAF continued to protect the invasion fleet and ensure any enemy ground-based counterattack faced air attack. As the Allies could put in the air 12,000 aircraft at this stage, the Luftwaffe's aerial fightback was pitifully inadequate. On D-Day alone, the Allied air forces flew 15,000 sorties compared to the Luftwaffe's 100. Not one single Allied aircraft was lost to enemy fire on D-Day.

Utah

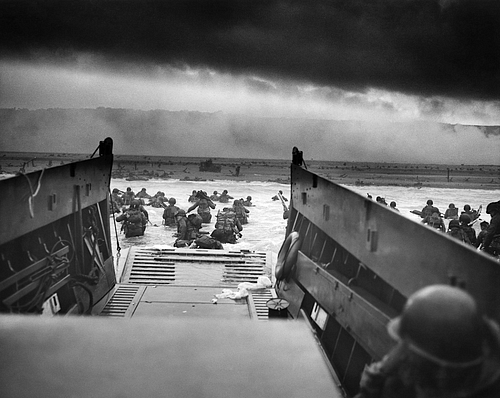

Shallow-bottomed LSIs (Landing Ships, Infantry) disgorged troops on the beach, the men having to survive mines and enemy fire. Smoke bombs were fired to obscure the beach and the men waded through the last 300 yards to reach the shore. The LSIs had landed a mile further south than intended, but this meant most of the defences were avoided and by noon the beach had been cleared and only six men had been killed; around 200 were lost in the day. 23,250 troops were landed here on D-Day. Utah had been easy, but next door at Omaha, an entirely different drama was unfolding.

Omaha

Establishing a beachhead at Omaha was the tough task given to the battle-experienced 1st US infantry Division, nicknamed the Big Red One after their shoulder patch of that colour. The defence was robust here, and they had two advantages: a high bluff and an entire extra division stationed there for a training exercise. Right from the off, the US troops suffered from the heavy seas that made the landing extra difficult. In the 200 assault vessels, men, when not being seasick into them, were obliged to use their helmets to frantically bail water. 27 of the 96 tanks were immediately lost when released too far from shore. Almost all of the first wave of artillery pieces were lost in the same way. 13 of the 16 bulldozers – meant to rip down enemy obstacles – were lost. The defenders were able to use their pillboxes and gun emplacements to set up a withering crossfire against the attackers. Things picked up for the American troops when the shore defences came under naval and air bombardment. The men and equipment kept coming, but they were under heavy fire from the defender's gun batteries, machine guns, and mortars. Several landing craft were blown out of the water, including one containing the company officers. The men on the beach were pinned down and could not move forward or back, protected only by the smoke laid down for cover and what beach obstacles or wreckage they could get to. It had been the wrong decision by the assault commander not to take more tanks like the British and Canadian forces elsewhere. After three hours, a route off the beach had still not been won. The landing of more materials and men was halted.

Engineers mustered what equipment they could and began to blast pathways away from the wreckage of men and machines that was now Omaha Beach. The defenders had no reserves (and none could be brought in as they were busy with the paratroopers causing havoc behind the main lines). Sheer numbers and determination meant the US troops finally won control of the beach by nightfall. On D-Day, almost 34,000 troops were landed at Omaha with 2,200 casualties.

Gold

On the beaches assigned to the British and Canadian forces, Sherman tanks with well-trained crews attacked the pillboxes while Crab flail tanks cleared mines to create safe lanes on the beach. They still faced artillery at Gold since the naval and aerial bombardment had not wiped out all of these positions. Mines on the beach also claimed many of the tanks before sheer numbers cleared the way. Wrecked tanks and armoured vehicles then became valuable points of relief for the infantry units swarming up the beach. To the west, the guns at Le Hamel caused havoc until finally put out of action by mid-afternoon. On D-Day, 24,970 troops were landed at Gold with 400 casualties.

Juno

The Canadian troops attacking Juno also experienced heavy seas and murderous fire from the defenders. The tide and rocky shoreline made good timing necessary and exposed the boats to enemy fire. In one wave, 20 out of 24 craft were blown out of the water. Bulldozers were able to land and clear the beach of obstacles. A combination of tanks and engineers with explosives steadily knocked out the defensive guns. By noon, troops were advancing inland. On D-Day, 21,400 troops were landed at Juno with 1,200 casualties.

Sword

Here, at the eastern end of the invasion, the fleet was in the range of the mighty guns of Le Havre. The Allied warships had their own big guns, and these were used to bombard the defences and the Le Havre guns. Under the cover of smoke, tanks went in first to preassigned exit points and to attack gun emplacements. Infantry followed under the usual hail of machine-gun fire and mortars. By 11:00 a.m., Allied troops were pushing on beyond the beachhead. On D-Day, 28,845 troops were landed at Sword with 630 casualties.

Packing Normandy

By the end of D-Day, 135,000 men had been landed and relatively few casualties were sustained – some 5,000 men. There were some serious cock-ups, notably the hopeless dispersal of the paratroopers (only 4% of the US 101st Air Division were dropped at the intended target zone), but, if anything, this caused even more confusion amongst the German commanders on the ground as it seemed the Allies were attacking everywhere. The defenders, overcoming the initial handicap that many area commanders were at a strategy conference in Rennes, did eventually organise themselves into a counterattack, deploying their reserves and pulling in troops from other parts of France. This is when French resistance and aerial bombing became crucial, seriously hampering the German army's effort to reinforce the coastal areas of Normandy. The German field commanders wanted to withdraw, regroup and attack in force, but, on 11 June, Hitler ordered there be no retreat.

All of the original invasion beaches were linked as the Allies pushed inland. To aid thousands more troops following up the initial attack, two artificial floating harbours were built. Code-named Mulberries, these were located off Omaha and Gold beaches and were built from 200 prefabricated units. A storm hit on 20 June, destroying the Mulberry Harbour off Omaha, but the one at Gold was still serviceable, allowing some 11,000 tons of material to be landed every 24 hours. The other problem for the Allies was how to supply thousands of vehicles with the fuel they needed. The short-term solution, code-named Tombola, was to have tanker ships pump fuel to storage tanks on shore, using buoyed pipelines. The longer-term solution was code-named Pluto (Pipeline Under the Ocean), a pipeline under the Channel to Cherbourg through which fuel could be pumped. Cherbourg was taken on 27 June and was used to ship in more troops and supplies, although the defenders had sunk ships to block the harbour and these took some six weeks to fully clear.

Operation Neptune officially ended on 30 June. Around 850,000 men, 148,800 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of stores and equipment had been landed since D-Day. The next phase of Overlord was to push the occupiers out of Normandy. The defenders were not only having logistical problems but also command issues as Hitler replaced Rundstedt with Field Marshal Günther von Kluge (1882-1944) and formally warned Rommel not to be defeatist.

Aftermath: The Normandy Campaign

By early July, the Allies, having not got further south than around 20 miles (32 km) from the coast, were behind schedule. Poor weather was limiting the role of aircraft in the advance. The German forces were using the countryside well to slow the Allied advance – countless small fields enclosed with trees and hedgerows which limited visibility and made tanks vulnerable to ambush. Caen was staunchly defended and required Allied bombers to obliterate the city on 7 July. The German troops withdrew but still held one-half of the city. The Allies lost around 500 tanks trying to take Caen, vital to any push further south. The advance to Avranches was equally tortuous, and 40,000 men were lost in two weeks of heavy fighting. By the end of July, the Allies had taken Caen, Avranches, and the vital bridge at Pontaubault. From 1 August, Patton and the US Third Army were punching south at the western side of the offensive, and the Brittany ports of St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient were taken.

German forces counterattacked to try and retake Avranches, but Allied air power was decisive. Through August 1944, the Allies swept southwards to the Loire River from St. Nazaire to Orléans. On 15 August, a major landing took place on the southwest coast of France (French Riviera landings) and Marseille was captured on 28 August. In northern France, the Allies captured enough territory, ports, and airfields for a massive increase in material support. On 25 August, Paris was liberated. By mid-September, the Allied troops in the north and south of France had linked up and the campaign front expanded eastwards pushing on to the borders of Germany. There would be setbacks like Operation Market Garden of September and a brief fightback at the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, but the direction of the war and ultimate Allied victory was now a question of not if but when.