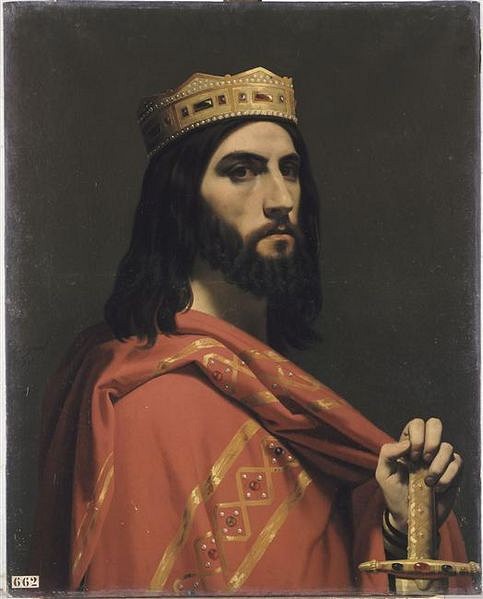

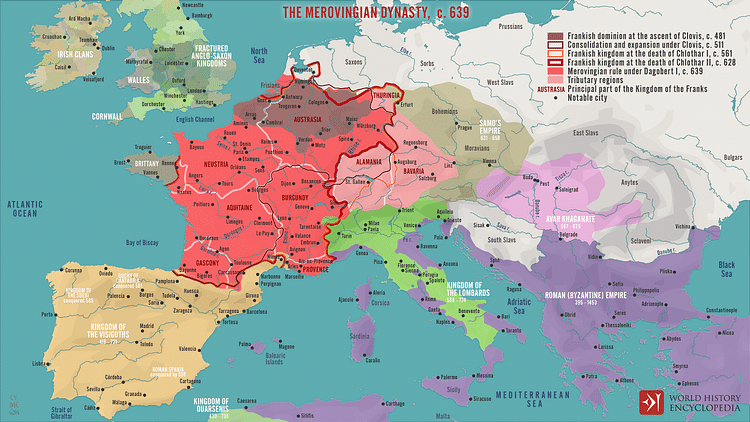

Dagobert I (l. 605-639) ruled as King of Austrasia from 623 to 634 and as King of All the Franks from 629 to 639. Together with the reign of his father, Chlothar II, the period of Dagobert's rule has been characterized as the peak of Merovingian power. However, Dagobert was the last king of the Merovingian Dynasty to exercise any significant royal authority.

Rise of the Aristocracy

Dagobert was born in 605, the son of King Chlothar II of Neustria (r. 584-629) and his wife Haldetrude. He was a scion of the Merovingian Dynasty, the ruling family of the Franks from the mid-5th century until 751. Dagobert's birth came at a time of great turmoil for Francia when the Merovingian kingdoms were being devastated by a civil war brought about by the rivalry between the family of Queen Brunhilda of Austrasia and that of Queen Fredegund, who was Dagobert's grandmother. By 605, it appeared that Brunhilda and her two grandsons had the upper hand; Fredegund was dead, and her son, Chlothar II, had been defeated in battle twice, his kingdom reduced to a small chunk of land between the Seine, the Oise, and the sea.

Chlothar's luck changed when, rather than combining their forces to finish him off, Brunhilda's two grandsons began fighting amongst themselves. In 610, the grandsons began a full-fledged civil war against one another; three years later, they were both dead, and the combined kingdom of Austrasia-Burgundy rested in the hands of an infant king Sigebert II, with his great-grandmother Brunhilda serving as regent. The Austrasian and Burgundian nobles were tired of the endless carnage and Queen Brunhilda's overbearing influence. In 613, several powerful Austrasian and Burgundian magnates including Warnachar, Pepin of Landen, and Arnulf of Metz, invited Chlothar II to invade their kingdoms. He accepted, marching into Austrasia and Burgundy with little resistance. Brunhilda and her great-grandchildren were captured and executed, and Chlothar II adopted the coveted title 'King of All the Franks', which had been created by King Clovis I (r. 481-511) but had gone unused since the death of King Chlothar I in 561.

Chlothar II kicked off his reign with the Edict of Paris of 614, which bolstered the power of the Frankish aristocracy. The edict decentralized Chlothar's newly united kingdom by leaving much of the power in the hands of regional authorities. In 617, Chlothar II also elevated the position of 'mayor of the palace' by appointing a man named Warnachar to the office for life; the mayor of the palace, which was once nothing more than head of the royal household, was now second in power only to the king himself. Each of the three Merovingian kingdoms of Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy had its own mayor of the palace to legislate and oversee affairs within the kingdom's own boundaries. Rather than consolidating the position into a single office, Chlothar II decided to let each kingdom retain its own mayor. Chlothar II strengthened his own position by securing the support of the aristocracy, but he achieved this at the expense of crown authority. As scholar Susan Wise Bauer explains:

Chlothar had made a devil's deal. He had the crown of the Franks, but two-thirds of his country was ruled by the mayors-whom he could not get rid of by legal means, who had the authority to legislate their own realms, and who were now able to act independently of the pesky royal children and aunts who had once controlled them. (251)

Early Life & Education

Meanwhile, Dagobert was being given an education befitting the eldest son of a Merovingian king. He spent his childhood at the royal villa of Reuilly, east of Paris, where he learned Latin, history, horseback riding, and weapons handling. In 615, he was invited to his father's court in Paris to learn the intricacies of court politics and administration. Although the Merovingian kingdoms were traditionally divided between each surviving son upon succession, Dagobert's younger half-brother, Charibert, was described in the Chronicle of Fredegar as "simple-minded" and was probably viewed as less capable than his elder brother. The expectations for the future of the Merovingian Dynasty, therefore, were largely placed on the shoulders of Dagobert alone.

Of course, this opinion was not shared by Sichilde, who was Charibert's mother. Sichilde was the daughter of a powerful count and had become Chlothar's primary wife in 618, having probably been one of his mistresses prior to that. Sichilde and her brother, Brodulf, lobbied for Chlothar II to make Charibert's inheritance equal to Dagobert's. Although Chlothar refused to do this, he would strengthen the ties between his own family and Sichilde's when he forced Dagobert to marry Sichilde's sister, Gomatrude, in 626.

King of Austrasia

In 623, Chlothar II was faced with a dilemma. The Austrasian nobles, including Bishop Arnulf of Metz and the powerful Pepin of Landen, mayor of the Austrasian palace, had been complaining that the king seemed to spend most of his time in Neustria, arguing that the royal presence gave Neustria an unfair advantage. While Chlothar was unwilling to move his court to Austrasia, which would undoubtedly upset his Neustrian subjects, he realized that the Austrasian magnates were too powerful to simply ignore. To appease them, he made the subkingdom of Austrasia a semi-autonomous entity with defined boundaries. He appointed Dagobert, who was 17 or 18 years old, as the king of Austrasia. This was a significant development, as the borders drawn up by Chlothar would help define the kingdoms of Austrasia and Neustria going forward.

As the new Austrasian king, Dagobert had minimal independence. He was overseen by the Austrasian aristocracy, headed by Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen, who used Dagobert to further their own interests. The magnates believed that Chlothar II had withheld lands during the partition that rightfully belonged to Austrasia, and they had Dagobert negotiate with his father for the return of those territories. Later, Arnulf and Pepin compelled Dagobert to order the assassination of Chrodoald, a Bavarian aristocrat and leader of the powerful Agilolfing clan, who had been giving trouble to the Austrasian leaders. As a ruler of a subkingdom, Dagobert was also still under the thumb of his father and could do little without his approval or assistance. In 623, while mounting a difficult military campaign against the Saxons, Dagobert was forced to ask Chlothar for help. The Saxons were defeated only by the combined might of the two Frankish rulers.

On 18 October 629, Chlothar II died at the age of 45. Upon traveling to Paris for the funeral, Dagobert discovered that Brodulf was conspiring to place Charibert on the throne of Neustria. According to Brodulf, Chlothar had amended his will on his deathbed to allow for this, having decided that he wanted Dagobert and Charibert to rule together. Dagobert consulted Landri, mayor of the Neustrian palace, and other leading officials, who refuted Brodulf's claims. Dagobert then had Brodulf assassinated and cut all ties with his family by divorcing his wife Gomatrude. He was now free to claim his father's title 'King of All the Franks', although he decided to placate his half-brother by letting him rule over Aquitaine as King Charibert II (r. 629-632).

King of All the Franks

Hoping to shed the influence of the Austrasian magnates, Dagobert moved his court from Metz to Paris. Of his previous Austrasian advisors, he took only Pepin of Landen to Paris, perhaps so he could keep an eye on him. Despite this attempt to disempower the Austrasians, they managed to remain influential throughout his reign by banding together; Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen consolidated their alliance with the marriage of Arnulf's son Ansegisel to Pepin's daughter Begga. This new family, known alternatively as the Arnulfings or Pippinids, would eventually produce the Carolingian Dynasty, the family that would ultimately supplant the Merovingians as rulers of Francia.

For now, however, Dagobert needed to establish himself as the King of the Franks. In 629, he entered the arena of international politics when he negotiated a treaty of 'perpetual peace' with the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (r. 610-641). On Heraclius' advice, Dagobert ordered all the Jews in his kingdom to be baptized. Around the same time, Dagobert married Nanthilde as his new queen consort and took Ragnetrude as a concubine; in 630, Ragnetrude gave birth to Dagobert's first son, Sigebert III. In 633, Nanthilde gave birth to Dagobert's second son, who would one day rule as Clovis II. Now, having proved his diplomatic skill with the Byzantine treaty, and having fathered two heirs, Dagobert's position in Francia appeared all the more secure.

In 632, Charibert II died, and his infant son, Chilperic, was mysteriously assassinated. The throne of Aquitaine passed back into the hands of Dagobert I, who now truly ruled over a united Frankish realm. The vast amount of land under Dagobert's control made him one of the most powerful and respected monarchs in western Europe, as well as perhaps the most powerful Merovingian king since Clovis I himself.

War with the Wends

To the east of Dagobert's territories, further east than the Elbe, there lived a group of Slavic people known as the Wends, led by a king named Samo. Samo was not a Slav himself, but a Frankish merchant who had earned the trust and friendship of the Wends by aiding them in their war against the Avars and had impressed them so much that they made him their king. Samo had secured his throne by marrying into the major Wendish families, marrying at least 12 women, and fathering 37 children. He led the Wends on raids into lands belonging to Germanic peoples who paid tribute to Dagobert and the Franks; in 630, these Germans petitioned Dagobert for help.

Dagobert had his own reasons to quarrel with Samo, since the Wends had robbed and murdered "a great multitude" of Frankish merchants (James, 105). After diplomatic relations were further upset by a haughty Frankish envoy, Dagobert decided the only course of action left was to punish the Wends through military might. In 631, he launched a three-pronged attack; his Lombard allies were to push north out of Italy, his Alaman allies were to march from their Transjuran settlements, while Dagobert himself would lead a Frankish army out of Austrasia. The Lombards and the Alamans each launched successful campaigns and defeated the Wends, but Dagobert suffered a decisive defeat outside the Slav fortress of Wogastisburg after a bloody three-day battle.

The cause of Dagobert's defeat, according to the Chronicle of Fredegar, was the demoralization of his army, which was mostly comprised of Austrasian troops; the Austrasians apparently still felt bitter that Dagobert had deserted them and moved his royal court to Neustria, and therefore did not feel much inclined to fight for him. In any case, the battle was a humiliation for Dagobert and an encouragement for Samo and his Wends, who began raiding deeper into Frankish territory. The Saxons offered to help Dagobert defend his borders in exchange for a remission of their yearly tribute of 500 cows. Dagobert accepted, though the Saxons' assistance had little effect; the next year, 632, saw further Wendish incursions into Thuringia.

Austrasian Revolt

The failure of the war against the Wends caused more internal problems for Dagobert. The Austrasians, who had seemed indifferent towards victory during the war itself, now complained that their lands were being ravaged by Wendish raiders. In 632, having had enough of Dagobert's perceived negligence, the Austrasian nobles revolted against his rule; the revolt was led by none other than the cunning Pepin of Landen.

The situation was diffused in 634, when Dagobert took a page out of his father's handbook by carving off Austrasia from the rest of his realm. Austrasia once again became a semi-autonomous subkingdom nominally ruled by Dagobert's three-year-old son, Sigebert III (r. 634-656). This was a move that, according to scholar Ian Wood, had "important long-term implications for the general structure of Merovingian Francia"(145). This partition reinforced the divisions between the kingdoms of Neustria and Austrasia that had originally been defined by Chlothar II eleven years earlier and reinforced the power of the Austrasian magnates, who now had an infant puppet king to rubber-stamp their agendas.

Later Reign

From his court in Paris, Dagobert exerted considerable influence over his remaining kingdoms, becoming the last Merovingian king to effectively do so. He hindered the ambitions of certain powerful nobles and was able to suppress several conflicts that had grown between various aristocratic families. On the advice of his chief counselor, Eligius (Saint Éloi), Dagobert centralized the minting of coins in Paris, in order to combat monetary fraud. He also spent his efforts reorganizing the systems of administration and justice in Francia.

Dagobert was a pious king, known for his generous donations to the Catholic Church and the clergy. He most famously patronized the abbey of Saint-Denis Basilica in Paris, which was expanded to house 500 monks plus their servants. He commissioned a new mausoleum in the basilica, which held the remains of the Christian martyr Saint-Denis and would one day be the customary resting place for the kings of France. Together with Eligius, Dagobert founded the monasteries of Solignac, near Limoges, and Saint Martial on the Île de la Cité in Paris. Dagobert also cultivated a reputation as a great patron of the arts, as evidenced by goldsmiths' work that he commissioned for churches.

Despite his unimpressive track record in military campaigns, Dagobert tried his luck again in 631, when he sent an army to Spain to help Sisenand, governor of Septimania, in his struggle for the throne of the Visigoths. As a show of gratitude for Dagobert's assistance, Sisenand sent the Frankish king a gift in the form of a 500-pound gold dish. With Dagobert's help, Sisenand succeeded in taking the Visigothic throne, which he held until his death in 636. In 635, Dagobert sent an army to crush a Gascon revolt; the Merovingian army, commanded by ten dukes, easily defeated the Gascons and sent them fleeing into the mountains. Despite this victory, the Frankish army was ambushed by the Gascons during its march home in the valley of the Soule; several important Frankish nobles and officials were killed in the ambush. That same year, Dagobert threatened to send an army to quell unrest in Brittany, but the simple threat of invasion was enough to bring the Bretons to terms.

Death & Legacy

Dagobert I died on 19 January 639, at the age of only 36, and was the first of the Frankish and French kings to be interred in the abbey of Saint-Denis Basilica. Upon his death, the kingdoms of Neustria and Burgundy were inherited by his younger son King Clovis II (r. 639-657) while his eldest son, King Sigebert III, continued ruling in Austrasia. Both of Dagobert's successors were still children upon his death, allowing the ambitious mayors of the palaces and the Frankish aristocrats to begin ruling in the young kings' names. The concessions made by Chlothar II and Dagobert put the aristocrats in such a position that even when the kings came of age, it was the mayors who held the real power, leaving the Merovingian king as little more than a figurehead.

Sigebert III and Clovis II are therefore considered the first of the "rois fainéant", or "do-nothing kings", the name ascribed to the Merovingian kings of this period by the chronicler Einhard. The mayors of the palaces became the true powers behind the throne as the Merovingian Dynasty faded into irrelevance. Yet the decline of the Merovingian Dynasty did not equate to the decline of the Franks; indeed, the Franks continued to grow in their power and influence. In 751, more than a century after Dagobert's death, the charade was finally ended by Pepin the Short, who deposed the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, and took the throne for himself. Pepin the Short (r. 751-768) became the first king of the Carolingian Dynasty, the family that would produce Charlemagne (l. 742-814).

Because the lingering demise of the Merovingian Dynasty began with his own death, Dagobert I is often considered the last Merovingian king to wield any significant royal power for himself. Indeed, Dagobert's reign has been regarded by some historians as the summit of Merovingian power. He was highly regarded by contemporary European rulers and may have possessed a personal fortune larger than any previous Frankish king. Yet he is perhaps most recognizable today for his appearance in a popular French nursery rhyme, Le bon roi Dagobert ("The Good King Dagobert"), which takes the form of a series of satirical conversations between Dagobert and his chief advisor Saint Eligius (Saint Eloi). The text of the rhyme became popular as an expression of anti-monarchical sentiment during the French Revolution (1789-1799) and remains popular today. In the first verse, Dagobert accidentally puts his pants on inside out:

The good King Dagobert

Had his breeches inside out.

The great Saint Eloi told him,

'O my king, your Majesty

Has his breeches inside out.'

'Indeed,' the king told him,

'I'm going to put them right side out.'(mamalisa.com)

Overall, the reign of Dagobert I was a significant turning point in French and European history. With him, died the authority of the great Merovingian Dynasty, the family of Clovis I. Out of his reign, came the seed that would eventually blossom into the Carolingian Dynasty, a family that would do much to define Europe in the Middle Ages.