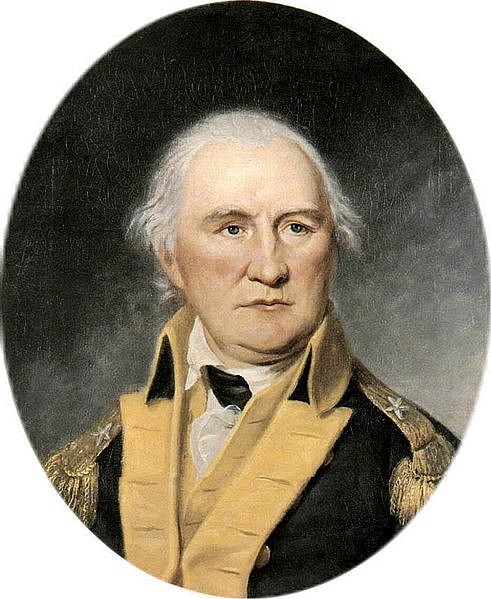

Daniel Morgan (l. c. 1735-1802) was an American frontiersman and soldier, most famous for leading a corps of riflemen during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). He rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Continental Army and played key roles in several American victories, including the Battles of Saratoga and the Battle of Cowpens.

Early Life & Service in the French & Indian War

The details of Daniel Morgan's early life remain obscure, but he is believed to have been born in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, in either 1735 or 1736 to a family of Welsh immigrants. Some sources claim that he was a cousin of fellow American frontiersman Daniel Boone. During the winter of 1752, when Morgan was about 17, he left home after a bitter argument with his father and headed west. He made it to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he stopped to perform odd jobs and make some money before continuing his journey once the snow had melted. Sometime in the spring of 1753, he arrived in the town of Winchester, Virginia, which was then on the colony's frontier. Morgan liked the little town well enough that he decided to settle there; he initially found work running a sawmill before eventually accepting a job as a wagon driver. Life as a wagon driver satisfied the young Morgan's thirst for exploration and adventure, as his work took him to the towns and outposts scattered along the Virginian frontier.

Around this time, tensions were mounting between Virginia and the colony of New France, both of whom had laid claim to the fertile Ohio River Valley. In 1754, a company of Virginia militia under Colonel George Washington was sent to make the French and their Native American allies leave the Ohio Valley. The ensuing confrontation ended in bloodshed when Washington's force ambushed a company of French-Canadian soldiers at the Battle of Jumonville Glen (28 May 1754), sparking the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The following year, Major General Edward Braddock landed in Virginia with two regiments of British soldiers to enforce Virginia's claims to the Ohio territory; Braddock's army would need supplies, and Morgan volunteered to deliver flour, salt, and other provisions to the British army's base at Fort Cumberland, Maryland. When Morgan arrived, he and other wagon drivers were impressed into the expedition against their will and accompanied the army when it set out on 29 May 1755.

As Braddock's expedition made its way into the wilderness, the British officers quickly became irritated by the behavior of the Virginian wagon drivers and militia. The Virginians frequently brawled with one another and with British soldiers, were prone to drinking and gambling, and flirted shamelessly with Native American women. Such disdain led one British officer to strike Morgan with the flat of his sword; Morgan, unused to such military discipline, responded impulsively by pushing the officer down. For the crime of 'attacking an officer', Morgan was sentenced to receive 500 lashes upon the back, a punishment that was usually fatal. Morgan, however, endured the lashes without losing consciousness, even counting along with the drummer delivering the blows; later, Morgan would often joke that he owed the British one more lash because the drummer miscounted and only whipped him 499 times. The scars on Morgan's back were permanent, however, as was his consequent hatred for British officers.

Due to his injuries, Morgan was not with the main army when it was ambushed by the French and their native allies on 9 July 1755; General Braddock himself was mortally wounded and a large portion of his army was killed or wounded. Morgan helped transport the wounded back to Virginia in his wagon. Several months later, Morgan joined a company of Virginia Rangers operating in the Shenandoah Valley, to protect the frontier against attacks from France's Native American allies. In April 1756, Morgan and a companion were traveling through the woods, carrying dispatches for the town of Winchester, when they were ambushed by seven Native American warriors. Morgan's companion was instantly killed, while Morgan himself was hit with a musket ball that passed through his neck and exited out his cheek. Believing Morgan to be dead, the Native American warriors went to work scalping the companion, at which point Morgan jumped up, leaped on his horse, and made his escape. He recovered and continued to serve with the rangers until 1758 when the British capture of Fort Duquesne rendered the ranger companies unnecessary.

Morgan's Rifles

After the war, Morgan resumed his career as a wagon driver. His work often took him to the settlement of Battletown, where he drank, gambled, and wrestled with the local frontiersmen; his charismatic and jovial personality, along with his large size, endeared him to the frontiersmen who soon looked to him as a leader. Around this time, Morgan fell in love with Abigail Curry, and the couple began living together out of wedlock. They had two daughters in the 1760s, Nancy and Betsy, who were educated by Abigail herself until Morgan was able to afford a tutor. Due to his new familial responsibilities, Morgan gave up wagoning and rented some farmland. He grew tobacco and hemp, eventually becoming prosperous enough to purchase 255 acres of land from Abigail's uncle in the late 1760s. By 1774, Morgan also had ten enslaved workers. His life as a yeoman farmer was briefly interrupted in the summer of 1774, when he rejoined the militia to fight the Shawnee in Lord Dunmore's War (May to October 1774) on the Virginian frontier.

In April 1775, long-simmering tensions between Great Britain and the thirteen North American colonies finally boiled over into war. After the first shots were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April), thousands of New England militiamen began to lay siege to the garrison of British regulars in Boston, Massachusetts; this ragtag American force was soon reorganized into the Continental Army and placed under the command of General George Washington. To supplement this army, the Second Continental Congress opted to raise several companies of riflemen from the colonies of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. At the time, rifles were well-known in Europe as a hunting weapon but were still relatively unknown in North America; John Adams had written to his wife expressing his fascination with a "peculiar kind of musket, called a rifle" (Boatner, 935). The rifle took twice as long to reload as a musket and could not be fixed with a bayonet, which is why it was not commonly used as a military weapon prior to 1775. However, some members of Congress, particularly Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, recognized its potential. The long rifle (or the Kentucky rifle as it was better known) had a spiral-grooved barrel, which made the bullet rotate in flight; this gave the rifle a longer range and deadlier accuracy than a musket.

But the rifle would be useless if it were not put into the hands of an expert marksman. Lee believed he knew where to find such men: the Virginia frontier. The frontiersmen, whose lifestyle required proficiency with firearms, were known to be excellent shots; rumor had it that most of them could hit a target no larger than an orange from 200 yards (182 m). Additionally, they were known to travel long distances with minimal provisions. When Virginia approved the raising of two rifle companies, therefore, it was from the frontiersmen that recruits were sought. Morgan was unanimously elected captain of one of the companies, chosen for his "courage, conduct, and reverence for liberty" (Higginbotham, 22). Indeed, alongside a chance to defend American liberties, Morgan also sought to settle a personal score; the scars on his back had not been forgotten.

After kissing Abigail and his children goodbye, Morgan rode from town to town searching for recruits. He did not have trouble finding them; his reputation amongst the frontiersmen of Battletown preceded him, and everywhere he went he found crowds of men itching to pick up a rifle. Morgan supposedly selected recruits by hosting shooting competitions and only selecting the best. Ultimately, he recruited 96 men to his company. Most were tall and in their early twenties, each equipped with a rifle, tomahawk, and scalping knife, and were dressed in long hunting shirts, leggings, and moccasins (Higginbotham, 24). When the company was ready, Morgan led them to Boston, covering over 600 miles (965 km) in only 21 days; when they arrived at the American camp, General Washington was so moved by their feat of endurance that he shook hands with each man in the company as "tears streamed down his cheeks" (Boatner, 934).

Quebec & Saratoga

Morgan's riflemen participated in the Siege of Boston for about a month; they terrorized the British by taking shots at sentries and at officers who ventured out beyond the British lines. In September 1775, Morgan's company was ordered to participate in the American invasion of Quebec. Accompanying the second prong of the expedition under General Benedict Arnold, Morgan's riflemen endured a harrowing trek through the Maine wilderness before arriving outside the British-occupied city of Quebec in December. In the early morning hours of 31 December 1775, amidst a howling snowstorm, the Americans assaulted the city; a column of soldiers under General Richard Montgomery was to attack from the south, while Arnold's men were to assault from the north. After entering the city, the two sides would link up at a designated position in Quebec to complete the attack.

Arnold led the assault from the front and was wounded in the leg early in the fighting. Morgan assumed command and led the column forward, eventually coming up against a barrier that was defended by two cannons. Morgan put a ladder against the wall and urged his men onward; when they hesitated, Morgan climbed up the ladder himself. He was greeted by a hail of bullets, one passing through his hat and another grazing his cheek. The force of this volley knocked Morgan off the wall and into a snowbank – only for the resilient frontiersman to jump to his feet and climb back up the ladder. This show of bravery inspired his men, who followed him up the wall and stormed the barrier. The Americans pushed on until they reached the spot where they were supposed to rendezvous with Montgomery's men. The other American column, however, was nowhere to be found; unbeknownst to Morgan, Montgomery had been killed by grapeshot, and his men had fled. When Montgomery's men failed to show up, Morgan's troops lost their nerve and panicked, leading to their capture by the British. Morgan was held captive until September 1776, when he was freed in a prisoner exchange.

Morgan rejoined the Continental Army as a colonel, and in April 1777, he raised a fresh unit of 500 riflemen. In August, he was sent north to help General Horatio Gates defend the Hudson River Valley from a British army that was marching south from Canada. Gates' army took up a defensive position on the Bemis Heights, near the town of Saratoga, New York; on 19 September 1777, American scouts reported that the British army was attacking. Morgan's riflemen sallied forth and met a column of British regulars at Freeman's Farm, a location about a mile to the north of Gates' camp. The ensuing fight (the First Battle of Saratoga) lasted all day; supported by General Benedict Arnold and several units of Continentals, Morgan's riflemen held their ground. They excelled at fighting in the dense woods around Freeman's Farm, utilizing the cover of the foliage to reload their rifles.

The battle resulted in a stalemate, and both armies stayed put for several weeks. But the British were running low on supplies and, on 7 October, a detachment of redcoats under Brigadier General Simon Fraser set out in a desperate attempt to find a weakness in the American lines. The Americans knew about the British movements and ambushed Fraser's troops at the Battle of Bemis Heights (or Second Saratoga). Morgan's rifles swung around to the left and fired into the rear of the British troops. As General Fraser galloped back and forth atop his gray horse attempting to rally his men, Arnold realized he needed to be eliminated and told Morgan that "the man on the gray horse…must be disposed of" (Fleming, 67). Morgan had one of his riflemen target Fraser, who soon slid off his horse, mortally wounded. Shortly after Fraser fell, the British broke and fled. On 17 October 1777, British General John Burgoyne surrendered his entire army to General Gates; in Gates' report, he praised Morgan's riflemen, considering them the "corps the army of General Burgoyne are most afraid of" (mountvernon.org).

Cowpens

After the Battles of Saratoga, Morgan rejoined Washington's main army at Valley Forge. He remained with Washington until 18 July 1779 when he offered his resignation; although Morgan cited ill health, the more prevalent reason was that he had been passed over for promotion to the rank of brigadier general. He returned to his farm at Winchester where he remained until news reached him of Britain's invasion of South Carolina and of General Gates' subsequent defeat at the Battle of Camden (16 August 1780). With the British so close to threatening his home state, Morgan reluctantly re-enlisted, joining the Southern Department of the Continental Army now under the command of General Nathanael Greene. On 13 October 1780, Congress appointed Morgan to the rank of brigadier general and gave him command of a corps of light troops.

In mid-November 1780, most of General Greene's army was comprised of ill-equipped and untrained recruits. Since training such an army would take precious time, Greene decided to send General Morgan and 600 men to harass the British army along the Catawba River in order to occupy British attention while Greene trained the rest of the army at Cheraw. The plan worked; Morgan proved to be a pesky thorn in the British side, ambushing British companies and giving support to the Patriot militias operating in the South Carolina backcountry. In January 1781, the notorious British Legion (an elite unit of Loyalists) under Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton set out in pursuit of Morgan; Tarleton was an aggressive young officer who had earned infamy by allegedly slaughtering American troops who were trying to surrender at the Battle of Waxhaws (29 May 1780). Initially, Morgan tried to flee from Tarleton, but Tarleton traveled so fast that Morgan realized it would be better to stand and fight rather than risk being overtaken. He chose as his battleground a place called the Cowpens, a meadow about 500 yards (457 m) in length and width. "On this ground," Morgan told his officers, "I will beat Benny Tarleton, or I will lay my bones" (Fleming, 188).

At 3 a.m. on 17 January 1781, Morgan learned that Tarleton was fast approaching. He roused his tired men with the words, "Boys, get up! Benny's coming" (Fleming, 199), and arranged his army into three separate lines: the first consisted of skirmishers, the second of militia, and the third of regular Continental troops. His cavalry, commanded by Lt. Colonel William Washington (a distant cousin of the general) was placed at the rear. Before long, the British emerged from the woods, the green-coated Loyalist dragoons leading the charge; the skirmishers waited until the dragoons got within ‘killing distance' before firing off a few rounds and then retreating behind the second line of militia. The militia likewise waited for the British to draw near before firing two volleys, targeting officers, and then running behind the Continentals. Although the British advance kept coming, it started to falter; as the British ran into the third American line, Colonel Washington's cavalry struck the British right while the reformed militia attacked on the left. The startled British and Loyalist troops began to flee, with the battle over by 8 a.m. Morgan's victory at Cowpens was a turning point in the war in the South, preventing South Carolina from falling into British control.

Later Years

After Cowpens, Morgan linked up with Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette in Virginia to help pursue Tarleton as well as Morgan's old colleague Benedict Arnold, who had defected to the British. However, Morgan was badly afflicted by rheumatism and sciatica – before long he was no longer able to sit a horse and had to be conveyed in a litter. Due to these health issues, he resigned from the Continental Army once again in June 1781. Four months later, the Franco-American victory at the Siege of Yorktown brought an end to the active phase of the war, which officially ended with the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

Morgan retired to Winchester and returned to a life of farming. By 1796, he owned more than 250,000 acres (101,000 ha) of land; he built a large home on the property that he named 'Saratoga' after his most famous victory. He was admitted into the Society of the Cincinnati in recognition of his military service, and in 1790, he was awarded a gold medal for his victory at Cowpens. In 1794, he returned to military service to help subdue the Whiskey Rebellion and was promoted to major general. In 1797, he was elected to the House of Representatives as a member of the Federalist Party and served a single term. After leaving Congress in 1799, he returned to Winchester where he died on 6 July 1802, around the age of 67. Morgan left behind a legacy as a hero of the American Revolution, with many American towns and counties named in his honor.