David IV the Builder or the Restorer (also known as Davit IV Aghmashenebeli) was the king of Georgia from 1089 to 1125 CE. His long reign was marked by a substantial revival of medieval Georgia, he regained much of Georgia's lost territory and controlled a realm stretching from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea at his death. David's religious, military, and cultural reforms stabilized domestic life in Georgia and established the monastery of Gelati as a major cultural center. It was under David IV that Georgia was unified for the first time in centuries.

Chaos in Georgia

David inherited a realm that was rapidly falling apart. His father, George II of Georgia (or Giorgi II, r. 1072-1089 CE), was besieged by both internal rebellion and Muslim encroachment. The powerful Baghvash family rebelled repeatedly and other noble families tried to pull away from the center.

At the same time, the Seljuk Turks under Malik Shah (r. 1072-1092 CE), taking advantage of the Byzantine disintegration in Asia Minor, invaded in force in 1077 CE, sacking the major cities of Tbilisi and Erzurum and capturing the royal treasury. Annual Seljuk raids devastated Georgia; peasants were carried off as booty, and the Georgian capital of Kutaisi was looted. The Chronicle of David IV states that “here was no more sowing and harvesting in these lands; the forests crept back, and wild beasts and critters in the fields took the place of men” (Metreveli 171). George attempted to staunch the raids by agreeing to pay tribute and provide military service to Malik Shah, but this did little good since the Turkish raiders often operated outside of Malik Shah's control. George attempted to conquer Kakhetia with Malik Shah's support, but when Malik Shah decided to support the Kakhetians instead, the invasion turned into a rout.

By 1089 CE, Georgia was reduced to Abkhazia in the northwest part of the Caucasus. That same year, George's nobles made him abdicate in favor of his 16-year-old son, David IV.

Ascension of David IV

David's early years benefitted both from luck and planning. First, David threw away the Byzantine court titles that his ancestors had held and used for centuries. While Georgia had been de facto independent since at least the early 1000s CE if not earlier, the usage of the Byzantine court titles magistros, kouropalates, and nobilissimus implied fealty to the Byzantine emperor. By rejecting these titles, David was proclaiming clear independence for Georgia.

Next, David decided to pay off the Seljuks, which put an end to the Seljuk raids for much of the 1090s CE, allowing Georgians to return to rebuild towns and tend their fields. This helped stabilize the realm. In 1092 CE, the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk was assassinated by the Assassins and Malik Shah died that same year, severely diluting Seljuk strength. In 1095 CE, the First Crusade was called, and when crusaders started reaching the Middle East in 1097 CE, the Muslim enemies of Georgia to the south had to turn their attention to the crusading threat and ignore affairs in the Caucasus. This allowed David to cut off tribute to the Seljuks in 1099 CE, investing this money in the army and infrastructure instead.

Perhaps David's greatest early accomplishment, however, was reigning in the power of the nobles. He called out plots by the powerful duke Liparit Baghvash, initially forgiving him, but later exiling him to Constantinople. He then created the mstovarni, the king's secret police. This allowed him to foresee plots, and the plotters were often brutally punished with disfigurement or execution. When Liparit's son, Rati, died in 1103 CE, the Baghvash possessions of Kldekari and Trialeti were forfeited to the crown. This summary disposal of the once-powerful Baghvash family chilled independent streaks in other Georgian nobles.

Georgia Reunited

Even before the onslaught of the Seljuks, the kingdom of Kakhetia had remained outside of Georgian control. David decided to invade in 1103 CE, and entered unopposed; the king was a young inexperienced ruler, Aghsartan II, who was given over to David by the Kakhetian nobles. Some nobles did try to resist and called on the Muslim ruler of Ganja to help. The Kakhetian and Ganjan forces were routed at the Battle of Ertsukhi, and by 1105 CE, Georgia was reunited for the first time in centuries. Kakhetia was a wealthy land, and it had avoided Turkish raids through a treaty with the Seljuks. This added wealth helped Georgia continue to develop infrastructure and rebuild fortifications.

David formed a standing Georgian army loyal to him alone. According to one estimate, it may have been as large as 40,000 men, including an elite guard unit. David also instituted a strict discipline system for the army; it would be paid a salary rather than depend on loot, and swearing or rogue behavior would be disciplined.

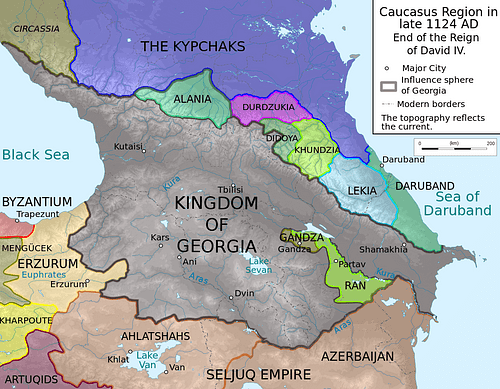

With a distracted Muslim world and new resources to improve his army, David had Georgian forces clear the remaining Turkish settlers and soldiers out of Georgia. In 1110 CE, the strategic town of Shamshvilde fell to the Georgians. David's forces crushed a Muslim army sent in retaliation. In 1115 CE, Georgian forces recaptured the city of Rustavi, cutting off Tbilisi from the Muslim east. Ossetia acknowledged Georgian suzerainty, as did the Chechens for a time. The Muslim states began to fear David's power and a combined Muslim force marched to Tbilisi. At the Battle of Didgori in 1121 CE, David crushed the combined Muslim forces. In 1122 CE, Tbilisi was recaptured and was declared Georgia's capital once again. In 1123 CE, David captured half of the Emirate of Shirvan and, in 1124 CE, he took the important Caspian Sea port of Derbent. Perhaps even more impressive, that same year the Armenian citizens of Ani, Armenia's former capital but now ruled by the Turks, called on David to liberate them. After a brief siege, Ani fell and David was declared king of the Armenians and all of Georgia. Muslim power in the Caucasus was destroyed. Georgian territory stretched across the Caucasus from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea.

Domestic Reforms

In addition to military successes, David also aimed to reform the state. He was known as a precocious king and even took his library with him on military campaigns. David took a strong interest in bettering Georgian society and instituted reforms in the medieval church and law.

The Georgian Church suffered from nepotism by the nobility, who promoted their underage and often unqualified sons to influential positions in the church hierarchy. Their behavior included sanctioning illegal marriages and sodomy. All of these practices were condemned by the Ruisi synod in 1104 CE, which also set minimum age and qualification requirements for ecclesiastical positions and laid out uniform church practice for all of the churches in Georgia. Separately, David unified the positions of the bishop of Chqondidi and chief secretary, thus imposing royal control over the church. He also founded the monastery of Gelati, which became a major source of Georgian intellectual life, as well as the resting place of Georgian kings. Gelati's prestige was raised by the addition of returning Georgian monks from the Middle East, who were not being tolerantly treated by the crusaders.

Later in his reign, David hosted a synod that attempted to reconcile the Armenian monophysite and the Georgian dyophysite Christians. While this synod was much less successful than the first, David practiced religious tolerance towards the Armenian Christians, which helped preserve Georgian rule over its new Armenian territories.

In governance, David established government offices and a court of appeals to hear Georgians' petitions. This allowed even the most marginalized in the population, such as widows and orphans, to have access to royal justice. He was also magnanimous to immigrants; he settled several thousand Qipchaq families that were rejected by the Kievan Rus in Georgia, which gave him a valuable military force as well. However, there were trust issues with the Qipchaqs, and both the crown and the Georgian populace were wary about allowing them too many privileges. They assimilated into Georgian life in the coming decades.

Foreign Influences & Foreign Affairs

In foreign affairs, David created alliances by practicing marriage diplomacy. David married his daughter Tamar to Manuchehr III (r. 1120-1160 CE), the future emir of Shirvan. He supposedly married his daughter Kata to Isaac Komnenos, the son of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE). He married his third daughter Rusudan to the heir to the Ossetian throne. He himself married Gurandukht (after divorcing his first wife, also called Rusudan), daughter of the Qipchaq chieftain, to cement his alliance with his new Qipchaq subjects. Through his careful planning, David had created a marriage network throughout the region.

The establishment of the monastery at Gelati spurred learning and the recording of medieval literature and history. At this same time, having absorbed Muslim territories and with close ties with Shirvan, Georgia started to absorb influences from Persian culture. While Byzantine culture remained strong, Persian works were translated into Georgian, and the works of Georgian historians began to reflect certain Persian stylistic norms. Persian words entered the Georgian vernacular. Even Persian courtly values of chivalry began to become popular in the Georgian court.

A Georgian Legacy

When David died in 1125 CE, he was buried in the Gelati monastery, which he had built. His heir, Demetrius I of Georgia (or Demetre I, r. 1125-1156 CE), inherited a powerful realm that dominated the Caucasus, was culturally rich and the rival of any of its neighbors. This was certainly a much-improved position on what David's own father, George II, had left him.

The main dark stain on David's legacy was his two marriages: Demetrius was the son of his first wife, Rusudan, while his surviving second wife, Gurandukht, had her own son by David, Vakhtang. Both surviving versions of David's will implore Demetrius to care for his brother and imply that the royal crown might pass to him in the future. This would lead to internecine strife between the two branches of the family over the next two generations, but ultimately Georgia would remain a powerful medieval state for the next century.