Democritus (l. c. 460 - c. 370 BCE) was a Greek philosopher and younger contemporary of Socrates, born in Abdera (though other sources cite Miletus) who, with his teacher Leucippus (l. 5th century BCE), was the first to propose an atomic universe. Democritus claimed that everything is made of tiny uncuttable building blocks known as atoms.

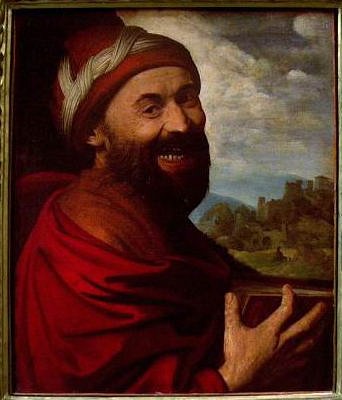

Very little is known of Leucippus, and almost none of his work has survived, but he is known by ancient writers as Democritus' teacher and apparently wrote on many subjects besides atomism. Democritus is known as the 'laughing philosopher' because of the importance he placed on cheerfulness. His work, like that of Leucippus, has been mostly lost, but later writers claim he wrote 70 books on topics ranging from farming to geometry, human origins, ethics, astronomy as well as poetry and literature, and fragments of his work are cited by later philosophers (notably Aristotle of Stagira (l. 384-322 BCE) who regarded him highly.

He was the first philosopher to claim that what people refer to as the 'Milky Way' was the light of stars naturally occurring and not the result of the actions of the gods, although, at the same time, he does not seem to deny the existence of spirits or the soul. Although his atomic theory makes clear that all things happen out of necessity – that one event naturally leads to the next – he maintained that people are responsible for their actions, that one must first consider the good of one’s soul over any other consideration, and that it was free will, not determinism, that directed one’s course in life.

He is considered one of the most important Pre-Socratic Philosophers (so-called because they pre-date and influenced Socrates of Athens (l. 470/469 - 399 BCE) who directly inspired Plato (l. 428/427-348/347 BCE) and the development of Western Philosophy. Democritus’ influence on Socrates is apparent in the fragments regarding ethics, but his concept of the atomic universe is also thought to have helped form Plato’s belief in an unchanging, eternal realm of which the visible world was only a reflection, at the same time his materialism challenged this very concept.

Democritus, in turn, was influenced by those who came before him, especially Parmenides of Elea (l. c. 485 BCE), Zeno of Elea (l. c. 465 BCE), and Empedocles (l. c. 484-424 BCE). The philosopher thought to make the greatest impression on him, however, besides his teacher Leucippus, was Anaxagoras (l. c. 500 - c. 428 BCE) who first proposed that all things are made up of "seeds" which cause them to be what they are. Democritus developed this "seed" theory into the concept of the atomic universe.

Travels & Reputation

Almost nothing is known of Democritus’ life. He is said to have been born and raised in Abdera and came from a wealthy family who was able to provide him with a good education. His father may have been Thracian nobility and was at least of the upper class. He may have studied with the philosopher Anaxagoras, though this is doubtful, but acquired a far-ranging education through travel and study with many masters.

When his father died, Democritus took his inheritance and left Abdera, traveling throughout the Mediterranean world and spending at least five years in Egypt studying mathematics before going south to Meroe. He is also believed to have stayed in Babylon and, according to the historian Diogenes Laertius (l. c. 180-240 CE), studied with the priests there. His association with Babylon, where the philosopher Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) also studied, may be the reason why later writers claimed Democritus was from Miletus.

The precise route and order of his travels is unknown, but he said to have also studied in India and possibly in Persia before returning to Abdera. Once he was back home, he devoted himself to further study, research of the natural world, and writing. He was a prolific writer (over 300 fragments have been identified as his work) who is said to have authored 70 books which were all well-received. Scholar Robin Waterfield comments:

Democritus covered not only familiar Presocratic chestnuts such as embryology and why magnets attract iron, but also wrote books on mathematics and geometry, geography, medicine, astronomy, and the calendar, Pythagoreanism, acoustics and other scientific topics, the origins of humans and animals, and even literature and prosody. Importantly, it is also clear that not only did he cover this wide range of topics, but he covered them in some depth – for instance, by raising and answering possible objections. He was therefore an important bridge between the dogmatism of many of the Presocratics and the fully fledged philosophy of Plato. (164)

As Democritus himself would say, “nothing comes from nothing” and he was clearly influenced by the Presocratic Philosophers who came before him. It is unclear how deeply Leucippus influenced him as nothing is known of this philosopher outside of his association with Democritus. Only two fragments of Leucippus’ work have survived, and the only complete sentence is his famous “Nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and by necessity” (Baird, 39). As this concept is later echoed by Democritus, it is probable Leucippus had a significant impact on his thought, but it is certain he, and most likely Leucippus, was influenced by Parmenides, Zeno of Elea, Empedocles, and Anaxagoras.

Philosophic Influences

Parmenides claimed that all of reality was of single substance and people only recognized duality in the world because they trusted in sense experience, which was faulty and could lead one into error. Trusting in one’s senses, one accepted changes and differences in life as the true nature of reality but this, according to Parmenides, would be a serious error because change was an illusion. One’s outward appearance might change and one’s circumstances but not one’s essence.

To Parmenides, that which is has always been and is unchangeable in its actual underlying form. That which is perceived as mutability, and change is a lie of the senses which separate one from knowledge of the self and true reality. Parmenides’ student Zeno of Elea defended his master’s claim through 40 mathematical paradoxes proving that change, and even motion, was an illusion. Zeno proved, mathematically, that if one wished to walk from Point A to Point B, one would first have to walk halfway and, before one reached the halfway mark, one would have to walk halfway to that and so on. One could never, therefore, actually walk from Point A to Point B, and the claim that one could was simply a lie of the senses.

Zeno used this paradox to show how reliance on sense perception separated one from actual reality, from the essence of what makes the world what it is and allows it to operate as it does. To these two philosophers, there did not need to be a First Cause for existence or a 'meaning' to any of it; that which was had always been and would always be.

Empedocles drew on this concept in claiming that the underlying form of the universe was love, a transformative and regenerating force expressed in the coming together and pulling apart of natural forces which produced the four elements that then informed everything else. Empedocles’ insistence on a single, unifying, force inspired Anaxagoras’ claim that all things are comprised of particles (which he called "seeds") which were all of the same substance but, arranged differently, produced different results, sometimes a human, sometimes an animal, a tree, grass, a mountain, a bird.

Like Parmenides, Anaxagoras believed the essence of reality was One, but this One was expressed in Many. For this to be so, there had to be something underlying every single aspect of the visible world and this "something" was "seeds" which, in a given arrangement, produced now one and now another visible phenomenon.

Anaxagoras and his seed-theory is the immediate inspiration for the atomic theory of Leucippus and Democritus. Waterfield explains:

Anaxagoras had argued that the natural substances which are the basic building-blocks of things were infinitely divisible: however much you divide a piece of wood, it will remain wood all the way. But it was presumably Leucippus, as the earliest of the atomists, who made an intuitive leap of genius and proposed that the world was ultimately made up of things which do not have qualities, as wood does. He said that if you were to continue to divide anything, at some point you would reach things which are not further divisible – they are atoma, indivisible. (165-166)

Waterfield credits Leucippus with this realization in keeping with the tradition that Leucippus was Democritus’ teacher – and it may well be that it was Leucippus who first came to this conclusion – but, if so, it was Democritus who developed it fully.

The Atomic Universe

In response to Parmenides' claim that change is impossible, and all is One, and Anaxagoras’ seed theory, Democritus tried to find a way to show how change and motion can be while still maintaining the unity of the underlying essence of the physical world. Democritus argued that everything, including human beings, is composed of very small particles which he called atomos ("uncuttables" in Greek), and that these atoms make up everything we see and are. Atoms were all of the same essence, but when "hooked together" in different ways, they formed different entities and visible phenomena.

Democritus claimed that, when one is born, one’s atoms are held together by a body shape with a soul inside, also composed of atoms, and while one lives, one perceives all that one does by an apprehension of atoms outside of the body being received and interpreted by the soul inside of the body. So when atoms have been combined into one certain form, a person looks at that form and says "That is a book", and when they have been combined in another, a person says "That is a tree", but however these atoms combine, they are all One, "uncuttable", and indestructible. When one dies, one’s body shape loses energy and one’s atoms disperse as there is no longer a soul inside the corpse to generate the heat that holds the body-shape atoms together.

According to Aristotle, Democritus claimed the soul was composed of fire-atoms while the body was of earth-atoms and the earth-atoms needed the energy of the fire for cohesion. Still, Aristotle also asserts, this did not mean these atoms were different atoms, rather that they were like letters of the alphabet which, though they are all letters, stand for different sounds and, combined in various ways, spell different words. To use a very simple example, the letters 'N', 'D' 'A' can be combined to spell the word 'and' or, with a different combination, spell the name 'Dan', which, while it has a different and distinct meaning from 'and' is still made up of the same letters.

Though there have been some claims made by materialists that Democritus' atomic view of human life denies the possibility of an afterlife, this is not necessarily true. As Democritus seems to have viewed the soul as causing motion and even life and that thought was the physical movement of indestructible, "uncuttable" atoms, it is possible a soul, even defined along materialist lines, would survive bodily death.

Democritus nowhere speaks of a "meaning" to life, however, outside of maintaining a cheerful disposition. Life, for him, did not need to be given a meaning whether while one lived it or in another realm that followed because the essence of life had always been and would always be; the meaning of existence was simply existence.

Ethics

In Democritus’ philosophy, one was born, lived, and died according to the coming together and dispersal of atoms. One might ask "What caused this event to happen?" and then define the cause of, say, an accident, but one was not encouraged to ask "Why did this happen?" in hope of some higher meaning. The famous line by Leucippus ("Nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and by necessity") is a concept which informs a great deal of Democritus' own writing especially his claim that "Everything happens according to necessity" in that atoms operate in one certain way and so, of course, that which happens in life does so out of the necessity of this operation whether one likes it or not.

While this claim would seem to deny the possibility of human free will, Democritus wrote extensively on ethics and clearly believed one could make free-will choices within the parameters of atomic determinism. Even though one was formed of these indivisible particles, both outwardly as a body, and inwardly as a soul, and these atoms came together and broke apart according to their own natural function, one still had control over one’s choices in life and was responsible for those choices. Professor Forest E. Baird comments:

Both the soul and the body are made up of atoms. Perception occurs when atoms from objects outside the person strike the sense organs inside the person which, in turn, strike the atoms of the soul further inside. Death, in turn, is simply the dissipation of the soul atoms when the body atoms no longer hold them together. Such an understanding of the person seems to eliminate all possibility of freedom of choice and, indeed, the only known saying of Leucippus is "Nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and necessity." Such a position would seem to eliminate all ethics: if you must act a certain way, it seems futile to talk about what you ought to do. (39)

Democritus addresses this objection, however, in stipulating that one is still responsible for what one does with one’s body and soul because a human being is able to distinguish between “right” – which Democritus associates with pleasures of the mind – and “wrong” – defined as sensual pleasures pursued without regard for consequences. Democritus recommended setting moderation in all things as one’s guide in order to maintain a balanced life. There was nothing inherently wrong in pursuing sensual pleasure, money, or power but one needed to recognize that these pleasures were fleeting and, if pursued without that recognition or without moderation, would lead to suffering.

Ethics, to Democritus, seems to have been primarily a means by which one lived a contented and composed life by recognizing the ultimate futility of trying to make life more than it is. In recognizing that everything is made of atoms which one has no control over, and responding to others in the same situation with compassion and cheerfulness, one could live free of the worry over "meaning" in life and concentrate on simply living.

Conclusion

The circumstances and precise date of Democritus’ death are as unclear as most of the events of his life, but it is well-established that he was highly regarded as an original thinker and writer while he lived and was clearly respected and often cited afterwards. He contributed significantly to the philosophical foundation which would be developed by Plato and did so by synthesizing and defining concepts previously suggested by other philosophers. Democritus did this in such a way that he is regarded by many in the present day as the "first scientist" as his thought and apparent method contributed to the development of that discipline.

His influence over the Greek and Roman writers who followed him is apparent not only in their philosophies but their references to him and his influence was clearly far-reaching and significant. Baird notes:

Democritus’ philosophy is important for at least two reasons. First, while atomism represents still another pluralistic answer to Parmenides, and while Leucippus was a Pre-Socratic, nevertheless Democritus was actually a slightly younger contemporary of Socrates and an older contemporary of Plato. Hence, Democritus’ atomistic materialism may be viewed as an important alternative to Plato’s idealism. Second, Democritus’ thought continued to have an impact, being taken up first by Epicurus and then, in Roman times, by Lucretius. (40)

The famous hedonist philosopher Epicurus (l. 341-270 BCE), in fact, drew on Democritus’ thoughts on pleasure in claiming that it was the chief good and end one should pursue in life. Democritus’ insistence on cheerfulness as the best response to life is mirrored in Epicurus’ philosophy, and both advocated moderation as the best means by which pleasures should be pursued and life lived to its fullest.

Epicurus, however, is only one of many who were influenced by Democritus’ work from ancient times to the present. Thinkers and writers in the modern day have expressed their admiration for Democritus as well as acknowledging their debt to him, and he remains as highly regarded today as he was during his own time.