The Despotate of Epirus was one of the successor states of the Byzantine Empire when it disintegrated following the Fourth Crusade's capture of Constantinople in 1204 CE. It was originally the most successful of those successor states, coming close to recapturing Constantinople, but after 1230 CE, it was geographically limited to Epirus itself and occasionally the neighboring territories of Thessaly and the Ionian islands. For the next two centuries, Epirus mostly maintained its independence, although it had to navigate being at the end of the Byzantine and Italian spheres of influence. Finally, in 1479 CE, the last territories of the Despotate of Epirus were conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

From the Ashes

When the Byzantine capital of Constantinople was sacked in 1204 CE by the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 CE), the core territories of the Byzantine Empire in Europe were conquered by the Latins, while at the peripheries of the empire, three Greek (or Roman) successor states arose. The Empire of Trebizond, in northern Anatolia near Georgia, had emerged around the same time or even slightly before the fall of Constantinople. In the Anatolian heartland of the former Byzantine Empire, the Empire of Nicaea emerged.

Byzantine resistance in Europe was initially less coherent. Many Greeks marched with the Latin invaders, including Michael Komnenos Doukas, a cousin of the former Byzantine emperors Isaac II Angelos (r. 1185-1195, 1203-1204 CE) and Alexios III Angelos (r. 1195-1203 CE). In the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, Michael served Boniface of Montferrat, the new King of Thessalonica (r. 1205-1207 CE). But as the Latin forces headed west, Michael broke with the Latin army and headed to the land of Epirus, in northwestern Greece along the Adriatic Sea, where one of his relatives was the Byzantine provincial governor in the regional capital of Arta.

Protected to the east by the Pindus Mountains and to the west and south by the sea, the region of Epirus had long inculcated a spirit of independence since the days of Alexander the Great and Pyrrhus; under Michael, that region would become an independent political entity once more. Michael declared himself the ruler of the region and established Arta as his capital. He and his descendants would rule Epirus, with varying fortunes, for the next century, initially as a serious contender for restoring the Byzantine Empire, later as a Greek polity at the intersection of the Byzantine and Italian worlds.

Empire of Thessalonica

Initially, Michael I (r. 1205-1215 CE) agreed to be the Venetian representative in Epirus and arranged peace with the Latin states that had emerged in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, allowing Epirus to endure in those early years of Latin power. But after a few years, Michael had built up a sizable army and fought back against the Latins. He reconquered part of Thessaly, including the key city of Larissa, and recovered the important island of Corfu and the principal Adriatic port of Durazzo from Venice.

After Michael died in 1215 CE, his half-brother Theodore I Komnenos Doukas (r. 1215-1230 CE) would lead Epirus to its greatest height before suffering a catastrophic defeat. Under Theodore, Epirus tried to restore the Byzantine Empire. In 1217 CE, when the Latin Emperor Peter of Courtenay (r. 1216-1217 CE) tried to cross through Epirote territory, Theodore captured him. Theodore then led Epirote armies in a series of successful campaigns, pushing the Latins out of Thessaly, pushing back the Bulgarians, and, in 1224 CE, recapturing Thessalonica, the second city of the former Byzantine Empire. In 1227 CE, Theodore was crowned Roman emperor by the Orthodox Christian archbishop in Ohrid. The Empire of Thessalonica was now established and appeared to be on the cusp of recreating the Byzantine Empire.

By 1230 CE, Theodore had taken Adrianople and was within striking distance of Constantinople itself, but instead of marching on the Queen of Cities, Theodore turned north to fight the Bulgarians. On 9 March 1230 CE, the Bulgarians under Tsar Ivan Asen II (r. 1218-1241 CE) crushed the Epirote forces at the Battle of Klokotnitsa. Theodore was taken prisoner and Bulgarian troops poured into Macedonia and Epirus. Epirus' chances of restoring the Byzantine Empire died on the field at Klokotnitsa.

Michael and Theodore's brother, Manuel Komnenos Doukas (r. 1230-1241 CE), took over Thessalonica but survived on the goodwill of the Bulgarians and Ivan Asen. Theodore, now blind, returned to Thessalonica in 1237 CE and ejected his brother Manuel, who went off to rule Epirote territory in Thessaly until 1241 CE. Theodore did not rule in his own right but appointed his son John as emperor (r. 1237-1244 CE). For the past decade, the Empire of Nicaea had been steadily growing in strength under Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes (r. 1222-1254 CE). Especially after the death of Ivan Asen in 1241 CE, Nicaean territory in Europe grew exponentially. In 1242 CE, Doukas Vatatzes forced John to renounce his imperial title and accept the lesser Byzantine title of despot instead. In 1246 CE, Doukas Vatatzes ejected John's brother, Demetrios Komnenos Doukas (r. 1244-1246 CE), from Thessalonica and formally incorporated the city into the Empire of Nicaea.

The True Despotate

While the Empire of Thessalonica crumbled, Epirus had become independent once more. After the Battle of Klokotnitsa, Michael II Komnenos Doukas (r. 1230-1267/1268 CE), the son of Michael I, declared himself ruler of Epirus. After the demise of the Empire of Thessalonica, Epirus was the only Greek state in Europe left to oppose the Empire of Nicaea. Although Michael initially fought to resist the Nicaeans, peace was made between the two states, sealed with a marriage alliance and the title of despot being bestowed on Michael and his son. While the early rulers of Epirus had not been beholden to the Empire of Nicaea, Michael II's reign starts the true Despotate of Epirus, as its rulers from him through the end of the state bore this title, granted by the Empire of Nicaea, which, after 1261 CE, was the restored Byzantine Empire.

Epirus was far from a complacent neighbor; its position was made especially complicated when the King of Sicily, Manfred (r. 1258-1266 CE) invaded Epirus in 1257 CE and occupied Durazzo and Corfu, as well as the key cities of Valona, Kanina, and Berat. To save face, Michael was forced to marry his daughter to Manfred, with her dowry consisting of those territories Manfred had already conquered.

Manfred's ambitions were far greater than Epirus. He allied with the Prince of Achaea and the combined Sicilian-Epirote-Achaean army marched to conquer the Empire of Nicaea, but Nicaean emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259-1282 CE) defeated the combined army at the Battle of Pelagonia in 1259 CE. Although Michael II and the Epirote forces had fled before the battle even started, Michael VIII's forces invaded Epirus and took the capital of Arta.

Michael II gathered support from Manfred in Italy and from Thessaly and retook Arta. Even after Michael VIII reconquered Constantinople in 1261 CE, restoring the Byzantine Empire, Michael II stubbornly refused to bow. Eventually in 1264 CE, with a Byzantine army marching on Epirus, Michael II came to the bargaining table. His son and heir Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas (r. 1267/1268-1297 CE) was married to Michael VIII's niece and Michael VIII confirmed the title of despot for Nikephoros.

Upon Michael II's death, Nikephoros reigned over Epirus, but Thessaly was given by Michael to his illegitimate son John Doukas. Nikephoros would be involved in an Italian invasion of the Byzantine Empire, this time led by Manfred's conqueror, Charles I of Sicily (r. 1266-1285 CE). Nikephoros eventually allied himself with Charles when Byzantine forces started to infringe on his territory. Michael VIII tried to submit to the Pope and reunify the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, culminating in official church reunification at the Council of Lyon in 1274 CE, in the hopes that the Pope could stop Charles. This allowed Nikephoros the opportunity to present himself as the protector of Orthodoxy against the heretical Byzantine emperor in Constantinople, but Nikephoros was forced to accept vassalage from Charles, and the Byzantines reconquered the northern territories of Epirus.

Charles's plans were destroyed with the Sicilian Vespers in 1282 CE, which caused him to lose the island of Sicily, leading to peace between Epirus and Byzantium for a decade. However, Italian ambitions emerged once again with Charles' son, Charles II (r. 1285-1309 CE), and Nikephoros married his daughter to Charles II's son, Philip of Taranto, providing several coastal cities as dowry. When Nikephoros died, Philip tried to seize the Despotate of Epirus, which he had a right to under Western feudal law, albeit not necessarily under Byzantine law. However, Nikephoros' widow, Anna, managed to secure the throne for her son Thomas (r. 1297-1318 CE).

The reign of Thomas was primarily marked by Epirus growing closer to the Byzantine Empire, in large part due to the influence of his mother, who was related to the Byzantine emperor. In 1315 CE, Thomas tried to realign himself with his brother-in-law Philip of Taranto, but before he could act, he was murdered by his nephew, Count Nicholas Orsini of Cephalonia. Greek rule over Epirus and the Komnenos Doukas Dynasty was at an end.

The House of Orsini

Count Nicholas (r. 1318-1323 CE) and the Orsini Dynasty from Cephalonia assumed the throne and married Thomas' widow. While Arta quickly accepted Nicholas, the second most important city in Epirus, Ioannina, switched its allegiance to the Byzantine Empire in 1318 CE. Nicholas swiftly appealed to Constantinople for recognition as despot, which Andronikos II granted him. Although the County of Cephalonia was now combined with the Despotate of Epirus, without Ioannina, the Despotate was shrunken from the days of the Komnenos Doukas. Nicholas tried to offer fealty and extremely generous terms to Venice in exchange for military assistance, but Venice refused. When civil war broke out in the Byzantine Empire in the early 1320s CE, Nicholas attacked Byzantine territory and besieged Ioannina, but he was killed by his brother John II Orsini (r. 1323-1335 CE).

John II convinced Ioannina to accept him as its governor on behalf of the Byzantine emperor and he converted to Orthodoxy and married into the Byzantine Palaiologos family. Soon, he received both the title of despot and recognition as the governor of Ioannina from the new Byzantine emperor, Andronikos III Palaiologos (r. 1328-1341 CE). John took advantage of seeming Byzantine weakness to fully reincorporate Ioannina back into the Despotate of Epirus. In 1333 CE, Epirus also annexed some land in Thessaly, but later that year, the Byzantine army under Andronikos III took all of this territory from Epirus. Meanwhile, John of Gravina deposed John as Count of Cephalonia in 1325 CE. In 1331 CE, an Angevin-backed army under Walter of Brienne forced the Despotate of Epirus to bow as a vassal of Naples.

Two years later, John was poisoned by his wife, Anna, and was succeeded by his young son Nikephoros II Orsini (r. 1335-1340 CE). When a Byzantine army arrived in the north to subdue the Albanians, the weak despotate was riven by pro- and anti-Byzantine factions, and, to avoid war, Anna capitulated and signed over Epirus to the Byzantines without a fight in 1338 CE. The young Nikephoros was ferried away to the Principality of Achaea, where the regent, Catherine of Valois, who was also the titular Latin Empress, equipped an army that invaded southern Epirus and recaptured Arta. Andronikos III returned in 1340 with his Grand Domestic, John Kantakouzenos, and after bloody sieges and Kantakouzenos' convincing, the rebels surrendered and Nikephoros was taken. After 135 years, Epirus was Byzantine once more.

When Andronikos III died in 1341 CE, war broke out between his widow and Kantakouzenos over who would be regent for the young John V (r. 1341-1391 CE). The civil war would last until 1347 CE and devastate Byzantium. Anna took advantage of the chaos to raise the flag of rebellion in Epirus once more, but the rebellion was quickly put down by one of Kantakouzenos' deputies.

Meanwhile, the Serbian ruler, Stefan Dusan (r. 1331-1355 CE), marched south and captured most of northern Greece, including Epirus, by 1348 CE. Stefan appointed his brother Symeon Uros as despot, and he was married off to Anna's daughter, but when Stefan died in 1355 CE, Serbia descended into chaos and Symeon left Epirus to fight his nephew for the Serbian throne. Into the chaos stepped Nikephoros, who had survived the Byzantine civil war, and now retook Thessaly and Epirus in 1356 CE. However, a rebellion by the Albanians led to Nikephoros' death in battle in 1359 CE. With his death, the last direct descendant of the first Komennos Doukas despots of Epirus was now gone.

The Italian Restoration

After Nikephoros' death, Symeon turned back from Serbia and retook Thessaly and Epirus, but this time under the title of emperor rather than despot. Soon, Symeon gave up Epirus to the Albanians, creating two new despotates, Aitolia and Akarnania, and appointing the Albanian leaders Gjin Boua Spata and Peter Losha to rule. The important city of Ioannina refused to accept Albanian rule, however, and Symeon's son-in-law, Thomas Preljubovic became the despot of Ioannina in 1367 CE. Upon Losha's death in 1374 CE, Spata reunited the two despotates; but despite regular Albanian attacks on Ioannina, that city remained outside of Albanian hands. Thomas successfully repulsed the Albanians and was even given the epithet “Albanian-slayer,” but the contemporary Chronicle of Ioannina describes his rule as a reign of terror and he was murdered in 1384 CE.

Upon Thomas' death, the Albanians under Spata attacked Ioannina, which had raised Thomas' widow Maria Angelina Doukaina Palaiologina (r. 1384-1385 CE), the daughter of Symeon Uros, as their leader. Maria quickly married the Florentine nobleman and adventurer Esau Buondelmonti (r. 1385-1411 CE). Esau received the title of despot from Byzantine Emperor John V. He quickly submitted as a vassal of the Ottoman Turks, the new great power in the region, to help defend against Albanian attacks. After Maria's death, he married the daughter of Spata in 1396 CE, but other Albanian tribes still attacked Ioannina, and in 1399 CE, Esau and his army were captured by a group of them. Esau was ransomed several months later.

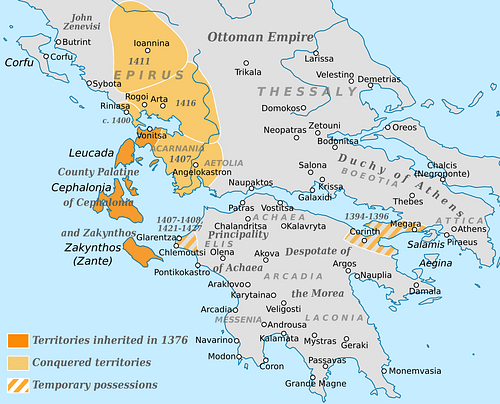

The next year, in 1400 CE, Carlo Tocco, the Count of Cephalonia, started to recruit a large mercenary army to attack the Albanians in Epirus. By 1408 CE, Akarnania was in Carlo's hands, and Carlo then started to captured more land to the north. When Esau died in 1411 CE, the people of Ioannina proclaimed Carlo I Tocco (r. 1411-1429 CE) their new leader just a few weeks later.

Alarmed by Carlo's increased strength, the Albanian lords banded together and, at the Battle of Kranea in 1412 CE, they routed Carlo's forces. Following the battle, Carlo developed close relations with the Ottoman Turks to ward off future Albanian attacks. In 1415 CE, Manuel II granted Carlo the title and crown of despot. The following year, in 1416 CE, Carlo marched on Arta, executed the last of its Spata rulers, and captured the city. The Despotate of Epirus was reunited.

Carlo had to contend with two significant complications: the ethnic diversity of Epirus (Greeks, Serbians, Albanians, and Italians) and repeated Turkish incursions from 1418 CE onward. Despite these troubles, the adventurous Carlo embarked on further expansion in 1421 CE; in the Morea, he forced the purchase of the major city of Clarentza, occupied the northwestern part of the peninsula, and effectively made the Principality of Achaea a vassal. However, when he attacked the Byzantine Despotate of the Morea, Byzantine forces decisively defeated Carlo's fleet in 1426 CE, and marriage between Carlo's niece and the future Constantine XI Palaiologos (1449-1453 CE) was arranged, with the dowry consisting of Carlo's Peloponnesian possessions.

The reunification of Epirus was short-lived. When Carlo died in 1429 CE, his possessions were split, with the islands, Ioannina, and Arta going to his nephew, Carlo II Tocco (r. 1429-1448 CE), and Aitolia and Akarnania being split between his three illegitimate sons, Ercole, Menuno, and Torno. The infighting began immediately, and Ercole and Menuno appealed to the Ottomans for help. In 1430 CE, Ioannina surrendered to the Ottomans to spare the city from destruction, as the city of Thessalonica had suffered only months before. Carlo II was allowed to remain as lord of Arta after submitting as a vassal to the Ottomans. Carlo would never be crowned despot by the Byzantine emperors, thus making Carlo I the last official despot of Epirus.

Carlo II attempted to resist Ottoman rule in the 1440s CE, but the Ottomans quickly forced him to submit to vassalage again. Just six months after Carlo's death, Arta was captured in 1449 CE by the Ottomans. His young sons were allowed to rule in the Ionian islands and maintain the three castles they had left on the mainland. The reign of Leonardo III Tocco (r. 1448-1479 CE) was merely waiting for the hammer of the Ottomans to fall on the last Epirote possessions. By 1460 CE, only the castle of Vonitsa was left on the mainland. Pleas for help to Venice, Aragon, and the Papacy met with paltry sums of money and empty or noncommittal promises. In 1479 CE, an Ottoman fleet conquered Vonitsa, Cephalonia, Ithaka, Zante, and Lefkada within a matter of weeks. Leonardo III had fled with what treasure he could gather. His brother Antonio returned with a Neapolitan fleet in 1481 CE, and briefly recaptured Cephalonia and Zante, but he was killed in 1483 CE. With his death, the Despotate of Epirus, the final direct legacy of the Byzantine Empire in Greece, was at an end.