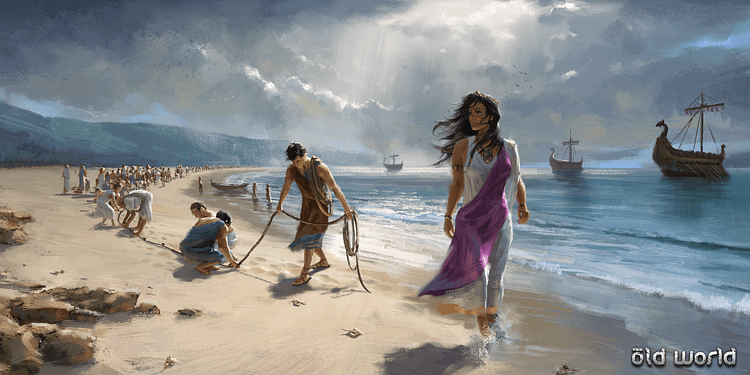

Queen Dido (aka Elissa, from Elisha, or Alashiya, her Phoenician name) was a legendary Queen of Tyre in Phoenicia who was forced to flee the city with a loyal band of followers. Sailing west across the Mediterranean she founded the city of Carthage c. 813 BCE and later fell in love with the Trojan hero and founder of the Roman people Aeneas. The tale of Dido is most famously recounted in Virgil's Aeneid but she appeared in the works of many other ancient writers both before and after.

Dido & Pygmalion

The earliest surviving mention of the founding myth of Carthage appears in the work of Timaeus of Taormina, a Greek historian (c. 350-260 BCE) whose original texts do not survive but which are referred to by later authors. Timaeus was the first to present the foundation of Carthage as occurring in either 814 or 813 BCE. An additional source on the historical Elissa is Josephus, the 1st century CE historian, who quotes Menandros of Ephesus' list of 10th-9th century BCE Tyrian kings, which includes mention of an Elissa, sister of Pygmalion (Pumayyaton), who founded Carthage in the seventh year of that king's reign.

The most famous version of the Dido story, though, is found in Virgil's Aeneid. The 1st-century BCE Roman writer describes Dido as a daughter of Belus, the King of the Tyre in Phoenicia. We are told that her Phoenician name was Elissa but the Libyans gave her the new name Dido, meaning 'wanderer'. Virgil recounts that Dido's brother, Pygmalion, cheated his sister out of her inheritance and then, in order to keep the throne of Tyre, killed Dido's husband Sychaeus. In another version, Dido married Acherbas (Zakarbaal), her uncle and priest of Melqart (or Baal) who was similarly executed by Pygmalion to acquire his wealth. Dido then fled the city with a loyal following (which included the military commanders Bitias and Barcas) and a hoard of the king's gold to sail west and a new life.

Foundation of Carthage

Dido's first stopping point was Kition on Cyprus, where she picked up a priest of Astarte after promising him that he and his descendants could be the High Priest at their new colony. A group of 80 young women, prostituted there in the name of Astarte, were taken along too, and the whole group sailed for North Africa where they founded their new city. Initially, the colonists were helped by the nearby Phoenician colony of Utica, and the local Libyan people (led by King Hiarbas) were willing to trade with them and offered to rent a piece of suitable land. The condition was that they could only have the area of land covered by an ox-hide. The resourceful Dido had the hide cut into very fine strips and with these encircled a hill which, in time, became the city's citadel and known as Byrsa Hill after the Greek word for ox-hide.

The name of this new settlement was Qart-hadasht (New Town or Capital), and its location on a strategically advantageous position on a large peninsula of the North African coast was selected to offer a useful stopping point for Phoenician maritime traders who sailed from one end of the Mediterranean to the other.

Archaeological finds of Greek pottery and the remains of housing dating to the mid-8th century BCE suggest already the presence of a large settlement and so confirm at least the possibility of the traditional founding date. Phoenician cities had already founded colonies around the Mediterranean, and so Carthage was by no means the first, but in a relatively short time, it would become the most important, go on to found its own colonies and even eclipse Phoenicia as the most powerful trading centre of the time. Carthage's prosperity was based not only on its location on trade routes but it also benefitted from an excellent harbour and control of fertile agricultural land. In honour of their founder Carthage minted coins from the 5th century BCE, and some have identified the female head with Phrygian cap seen on many of them as representing Dido. Some Roman writers suggest that Dido was deified, but there is no archaeological evidence from the Carthaginians themselves that this was so.

Dido & Aeneas

Roman writers, perhaps starting with the 3rd century BCE poet Naevius in his Bellum Poenicum, have Dido meet the Trojan hero Aeneas, who would found his own great city: Rome. In the myth of Rome's founding father, Aeneas came to Italy after the destruction of Troy at the end of Trojan War. This was four centuries prior to the founding of Carthage, so it is, therefore, chronologically impossible the two did meet if indeed they ever existed anyway. Virgil then follows with his own take on the myth in his Aeneid in what has become the classic version of the story. He informs us that Aeneas is blown off course in a storm but is directed by Venus to land at Carthage. Dido had been resisting a long line of suitors ever since her husband was murdered back in Carthage, but when she was struck by Cupid's arrow at the command of Venus, she fell in love with the hero. Once, separated from their entourage in a storm, the two make love in a cave. Unfortunately, the romance is short-lived for Mercury, sent by Jupiter, then prompts Aeneas to leave his love and continue the voyage which will fulfil his destiny as Rome's founder. When the Trojan resists Dido's calls to stay and sails away, it is then that the queen throws herself on a funeral pyre, but not before she pronounces a terrible curse on the Trojans, thus explaining the inevitability of the brutal Punic Wars between Carthage and Rome:

Let there be no love between our peoples and no treaties. Arise from my dead bones, O my unknown avenger, and harry the race of Dardanus with fire and sword wherever they may settle, now and in the future, whenever our strength allows it. I pray that we may stand opposed, shore against shore, sea against sea and sword against sword. Let there be war between the nations and between their sons for ever. (Bk. IV: 622-9)

According to another tradition, earlier than Virgil, Dido was forced to marry the Libyan king Hiarbas. To avoid this arrangement Dido built a large fire as if she were about to make an offering but then threw herself into the flames. It is also interesting to note that in Virgil's version Dido is given a sympathetic portrayal and this perhaps reflects the Augustan age when Carthage, no longer the hated enemy of previous centuries, was being rehabilitated into the Roman Empire.

Legacy

The legend of Dido became popular with later writers such as Ovid (43 BCE – 17 CE), Tertullian (c. 160 – c. 240 CE), the 14th-century authors Petrarch and Chaucer, and she appears as a central figure in the operas of Purcell (Dido and Aeneas) and Berlioz (Les Troyennes) amongst others. A female leader was exceptionally rare in ancient reality and mythology, and so Dido has captured the imagination for millennia. As the historian D. Hoyos summarises, 'The romantic and dramatic story of Elissa quite possibly rests on a basic historical reality, even if efforts to treat all its details as sober fact should be avoided' (12). This position is supported by M.E.Aubet, 'there are too many coincidences between the eastern and the classical sources to allow us to think that the story of Elissa had no historical basis' (215).