Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (also spelt Velásquez, 1465-1524) was a Spanish conquistador who conquered Cuba in 1511, became the island's first governor for the next decade, and sponsored expeditions of conquest directed at the American mainland, notably the one led by Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) which conquered the Aztec civilization of Mexico.

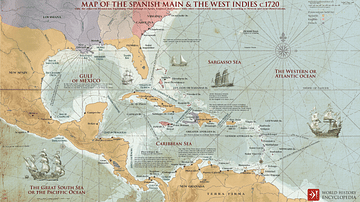

Velázquez founded such crucial colonial trading ports as Havana and Santiago, both of which were used as bases for expeditions which continued the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Velázquez's authority as the administrator in charge of the exploitation of resources on the American mainland was challenged and finally overtaken by Cortés after he sent back to Spain the compelling argument of tons of Mesoamerican gold and other treasures.

Early Life & Career

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar was born in 1465 in the ancient Castilian town of Cuéllar, Spain. His family was a distinguished one; Velázquez could count a number of castle commanders, judges, and royal courtiers, as well as the founder of the prestigious Calatrava military order amongst his ancestors. Velázquez had gained military experience during the Reconquista before he decided to put these skills to colonial use and try and make his name and fortune in the New World.

Conquest of Cuba

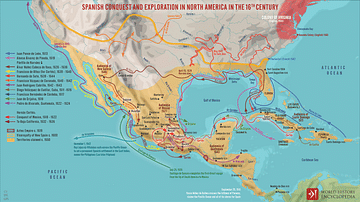

Spanish exploration of the Americas began in 1492 with the first voyage of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506). Velázquez made it to the New World as a member of Christopher Columbus' second voyage in 1493. There then proceeded a whole series of expeditions to colonise territory, starting with the island of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic/Haiti) in 1494. It was here that Velázquez made a name for himself. Ruthlessly quashing Arawak Indian rebellions and making a fortune in the process, Velázquez rose to become an aide to Nicolás de Ovando, then governor of Hispaniola (ruled 1502-1509). He proved to be an able and highly disciplined colonial administrator.

The Spanish Empire continued to spread through the Caribbean, to Puerto Rico in 1508 and Jamaica in 1509. The Spanish were seeking natural resources, especially gold and silver, but also slaves and land which had the potential for agricultural development and to support colonies. There were also those who wished to spread the Christian religion. In 1511, the Spanish turned their covetous gaze towards the large island of Cuba, then known as Fernandina.

Velázquez was made the governor of Cuba by Diego Columbus (1480-1526), the nominal head of the Spanish Indies (the Spanish Empire in the Americas), but first he had to conquer the people already living there. Velázquez also had to fund the expedition himself. He first landed on the eastern side of the island at what became the town of Baracoa in 1511 and then worked his way westwards. Spanish weapons and cavalry ensured victories against the indigenous tribes, but there were pockets of stiff resistance, notably those Taino Indians led by Chief Hatuey. This chief was eventually captured and, inevitably, sentenced to death for daring to protect his homeland. According to the Dominican friar and chronicler Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484-1566), Hatuey was offered a quick execution if he first converted to Christianity and saved his soul. Hatuey rejected this offer on the grounds that if he went to heaven he would be obliged to spend eternity with Spaniards. The Taino leader was burnt at the stake.

Colonial settlements were also established at Bayamo, Havana, Puerto Principe, Trinidad, and Santiago de Cuba (which became the capital). Velázquez proved to be an expert at choosing good locations for new towns, and most continue today to dominate their respective regions. Havana, in particular, with its magnificent harbour, became for centuries the jewel in the colonial crown for Spain. Velázquez's stone mansion still stands today in the centre of Santiago.

However, back on Cuba in the early 1510s, it took fully three years and countless massacres before the island was thoroughly under Spanish authority. As on the other Spanish-controlled islands, Velázquez gave his most loyal followers encomiendas, that is the right to extract free forced labour. The Spanish prospered thanks to the rich agricultural land that permitted large plantations to be formed. There was a good quantity of gold to be extracted from the island, too. On the other hand, the brutal new order coupled with the arrival of European diseases dramatically reduced the local population, so much that the island was practically depopulated. Labour for the sugar plantations had to be supplied from outside, in this case by African slaves.

The Yucatán Peninsula

Once Cuba was subdued, Velázquez began to look further afield, specifically to the Yucatán peninsula. An expedition was sent in 1517 under the command of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (1474-1517), who was killed along with most of his men after an encounter with Maya warriors, but not before they sent their reconnaissance report back to Cuba. Another expedition was duly launched in April 1518, this one led by Juan de Grijalva (1489-1527). A member of that second expedition was Pedro de Alvarado (c. 1485-1541), who did not get on at all with Grijalva, and he denounced his leader to Velázquez.

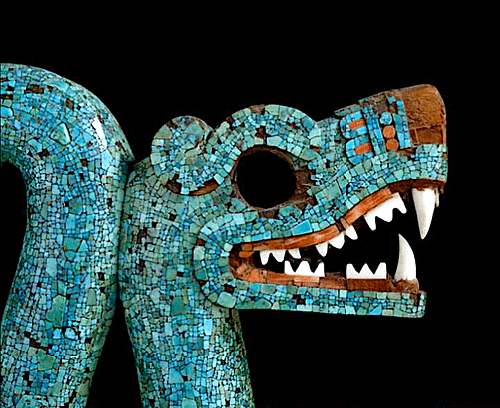

Velázquez had been delighted to discover from Grijalva's report that Mexico was not an island as had been thought. He was, too, greatly intrigued by additional reports of strange and seemingly ancient stone monuments and by the gold objects the conquistadors had brought back from Mexico. Grijalva was rebuked by Velázquez for not bringing back more gold, but those objects he had acquired matched well with the native rumours that far to the west lived a great and wealthy ruler called the "Lord of Culhua". We now know that this was indeed one of the honorific titles of the reigning Aztec ruler Motecuhzoma II (aka Montezuma, r. 1502-1520). In 1519, Hernán Cortés was commissioned with finding out more concrete information on the region and this mysterious lord, but he had grander ideas; perhaps already he was planning a campaign of territorial conquest.

Legal Battle with Cortés

When Cortés amassed an unusually large expedition force of over 500 fighting men and eleven ships, Velázquez realised his commander might well turn a reconnaissance/trade mission into one of conquest and so usurp his own position as the Caribbean's most powerful colonialist. At the last minute, Velázquez even tried to recall Cortés, but it was too late. Cortés was in a small boat heading out to his flagship when Vélazquez shouted out across the harbour: "How is this, compadre, that you are now setting off?" Cortés' distant reply was merely that all was well and everything was going to plan. The question was, whose plan?

The issue which preoccupied Velázquez hinged on the established process of conquest the Spaniards had been following for some decades. The Spanish Crown awarded an individual the status of adelantado, which gave them a right of conquest and to keep a certain amount of wealth acquired in that process. It was Velázquez who had the right of adelantado, not Cortés. This competitive pair actually had a history. Cortés had once been Velázquez's secretary in Santiago de Cuba, but the latter had grown suspicious of Cortés' loyalties and had him arrested for conspiracy. They had then made up since Velázquez subsequently awarded Cortés the title of alcalde, or chief magistrate, in Santiago. Aware that Cortés was a man of ambition, at least Velázquez had been wise enough to plant a few of his own men in the Mexico expedition – conquistadors like Diego de Ordaz – to report back on what exactly Cortés got up to.

Cortés landed on the Tabasco coast at Potonchan on the Americas mainland in March 1519. He then established a garrison at Veracruz on the coast but ignored fresh instructions from Velázquez to return to Cuba. Further, he had his men elect him their captain-general, theoretically giving him the right to conquest. The governor of Cuba responded in emphatic fashion and dispatched a new force of conquistadors to bring Cortés to justice. Led by Pánfilo de Narváez, this force was twice the size of Cortés'. Velázquez might have led this expedition in person since it was intended to continue the conquest under the governor's title of adelantado, but he was just then preoccupied with a smallpox epidemic on Cuba. As it happened, Cortés defeated a portion of the new arrivals in a skirmish and persuaded the rest to join his cause, not so difficult a task, such was the lure of Aztec gold.

Cortés made sure to send a quantity of the treasures he had acquired, with letters requesting royal support, directly to the king of Spain, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556). The king, no doubt aware of the delicacy of the situation between his senior colonial administrators, remained cautiously neutral, neither calling for an end to Cortes' conquest nor endorsing its further expansion. Ultimately, gold turned out to be a winning argument, and thanks to his looted treasure and letters of accusation that the Cuban governor was merely being greedy for more personal wealth, Cortés won the dispute. In October 1522, Cortés was granted the status of adelantado and so permitted to continue his conquest; he was, too, awarded the title of governor of New Spain as this new corner of the Spanish Empire was now known.

Velázquez, meanwhile, had been removed from office in 1521. He regained his governorship in 1523 after Cortés himself was discredited with further accusations of exceeding his authority and the much graver charge that he had not given the Crown its due share of the riches of Mesoamerica. Velázquez had little time to enjoy his return to power since he died of ill health the next year. As so often happened in the cutthroat world of the conquistadors, Velázquez had carved out a platform from which to launch a spectacular conquest, but it was those who came after that reaped the rewards.