Diocletian was Roman emperor from 284 to 305 CE. After the defeat and death of the Roman emperor Philip the Arab in 249 CE, the empire endured over three decades of ineffective rulers. The glory days of Augustus, Vespasian, and Trajan were long gone, and the once-powerful Roman Empire suffered both financially and militarily. There were constant attacks along the Danube River as well as in the eastern provinces. Finally, in 284 CE a man rose to the imperial throne who would completely change the face of the empire. His name was Diocletian.

Early Career

Diocles, who would become known to history as Diocletian, was born of humble origins on 22 December 245 CE in the Balkan province of Dalmatia. Like many of those who preceded him, after entering the Roman army, he rose quickly through the ranks, eventually becoming a member of an elite corps within the Illyrian army. Later, his abilities were rewarded when he became an army commander in Moesia, a northern Balkan province located just west of the Black Sea. In 283 CE, he accompanied the Roman emperor Carus to Persia where he served as part of the imperial bodyguard or protectores domesticis, a position he would continue under Carus' successor and son Numerian - unlike many who preceded him, Carus' death in 283 CE was due to natural causes.

The young emperor's reign would be short-lived. Although some suspect Diocletian of having a role in Numerian's death in 284 CE, the Praetorian Guard commander Arrius Aper, Numerian's father-in-law, shouldered the blame; he realized his son-in-law was incompetent and hoped to secure the imperial throne for himself. His plans, however, backfired. Diocletian would avenge the emperor's death by killing Aper in front of his own troops. After Diocletian was proclaimed emperor in November of 284 CE, he crossed the Strait of Bosporus into Europe where he met and defeated Carinus, Numerian's co-emperor and brother, at the Battle of River Margus - the young emperor was supposedly murdered by his own troops. With this victory, Diocletian gained complete control of the empire, assuming the name Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletian.

Dividing the Empire

Diocletian understood that a major problem in ruling a territory of the extent of the Roman Empire was its immense size. It was far too large to be ruled by just one person, so one of the first actions taken by the new emperor was to split the empire into two parts. Lacking an heir, in November of 285 CE, shortly after securing the imperial throne for himself, he named an Illyrian officer (who happened to be his son-in-law) named Maximian as Caesar in the West. The new Caesar, who would be promoted to Augustus one year later, immediately assumed the name Marcus Aurelius Valerius. Diocletian, who was never very fond of the city of Rome, would remain emperor in the East. The appointment of Maximian afforded Diocletian the time to deal with the continuing problems in the East, however, despite Maximian's position as co-emperor, Diocletian considered himself to be the senior emperor (something to which Maximian agreed), retaining the ability to veto any of Maximian's decisions. Gone was Augustus's Principate; in its place was the Dominate.

Unfortunately for both Diocletian and Maximian, peace in the empire could not be kept for long. The difficulties that had plagued the empire for the past several decades remained. As with his predecessors, problems soon erupted along the Danube River in Moesia and Pannonia. For the next five years, Diocletian would spend most of that time campaigning throughout the eastern half of the empire. An eventual victory in 286 CE would bring him not only a long-awaited peace but also the title of Germanicus Maximus. Diocletian demonstrated similar skills in Persia by defeating the Sarmatians in 289 CE and the Saracens in 292 CE.

Maximian was plagued by similar problems in the West. A rogue officer named Carausius, the commander of the Roman North Sea fleet, seized control of Britain and part of northern Gaul, proclaiming himself emperor. He had been awarded his command after helping Maximian defeat the renegade Bagaudae in Gaul. Later, when it was learned that he was keeping much of the "spoils of war" for himself, he was declared an outlaw and a death warrant was issued by Maximian. But, like many of the men who proclaimed themselves emperor, he met his death at the hands of someone under his own command, in this case, his finance minister Allectus.

The concept of a divided empire was apparently working. However, a situation that had faced every emperor since Augustus had to be addressed and that was succession. Diocletian's solution to this age-old problem was the tetrarchy - an idea that preserved the empire in its present state, with two emperors, but allowing for a smooth transition should an emperor die or abdicate. The new proposal called for two Augusti - Diocletian in the East and Maximian in the West - and a Caesar to serve under each emperor. This “Caesar” would then succeed the “Augustus” should he die or resign. Each of the four would administer his own territory and have his own capital. Although the empire remained split, each Caesar was answerable to both Augusti. To fill these new positions, Maximian adopted and then named his praetorian commander Constantius as his Caesar. Constantius had gained a reputation for himself after he led a number of successful campaigns against Carausius. Diocletian chose as his Caesar Galerius who had served with distinction under Emperors Aurelian and Probus.

This new arrangement was soon put to the test when trouble erupted in both Persia and North Africa. In Africa, a Berber Confederation, the Quinquegentanei, encroached upon the imperial frontier. In Persia, power was seized from the client-king Tiridates the Great in 296 CE, and the invading army advanced towards the Syrian capital of Antioch. Unfortunately, in his retaliation, Galerius used poor judgment and suffered an embarrassing defeat by the Persians. For this humiliation, he was publicly rebuked by Diocletian. Fortunately, he was able to gather reinforcements and defeat the Persians and their leader Narses in Mesopotamia - a favorable treaty was negotiated. In Egypt, an insurrection was led by Lucius Domitius Domitianus who, of course, declared himself emperor. His death - a possible assassination in December of 297 - brought Aurelius Achilleus to the throne. In 298 CE, Diocletian defeated and killed the would-be emperor at Alexandria. Maximian's eventual success in North Africa, Constantius's victories in the West and the reacquisition of Britain as well as victories by Galerius against the Carpi along the Danube brought peace to the empire.

Internal Administration

These victories finally allowed time for Diocletian to turn his attention to another project - domestic affairs. Although his greatest achievement would always be the tetrarchy, he also reorganized the entire empire from the tax system to provincial administration. In order to reduce the possibility of revolts in the outlying provinces, the emperor doubled the number of provinces from fifty to one hundred. He then organized these new provinces into twelve dioceses ruled by vicars who had no military responsibilities. These duties were assigned to military commanders. The military system was also reorganized into mobile field forces, the comitantenses, and frontier units, the limitanei.

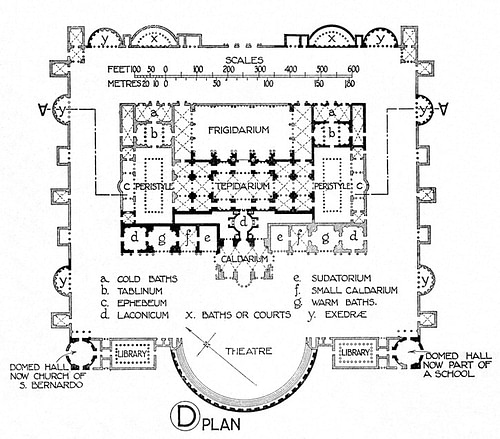

Unlike previous emperors, Diocletian avoided the patronage system, appointing and promoting individuals who were not only qualified but people he could trust. Unfortunately, as the importance of imperial Rome decreased and the center of power shifted to the East, many members of the Roman Senate lost much of their influence on administrative decisions. Because of the influence of Greece and Greek culture, the true center of the empire shifted to the East. This would become more prominent under Emperor Constantine, for he would turn a small Greek town, Byzantium, into a shining example of culture and commerce, New Rome. Rome was never either emperor's choice for a capital. Reportedly, and despite such grand projects as the new Roman baths - the largest in the Roman world on completion in 305 CE, Diocletian would only visit the great city once and that was just prior to his abdication. Even Maximian preferred Mediolanum (Milan). To Diocletian the capital was wherever he was; however, he eventually selected Nicomedia as his capital.

The empire's finances had always been a point of contention for most emperors, and since more money was necessary to fund the provincial reorganization and expanded military, the old tax system had to be scrutinized. The emperor ordered a new census to determine how many lived in the empire, how much land they owned, and what that land could produce. In order to raise money and stem inflation Diocletian increased taxes and revised the collection process. Individuals were compelled to remain in the family business whether that business was profitable or not. To stop runaway inflation he issued the Edict of Maximum Prices, legislation that fixed the prices of goods and services as well as wages to be paid; however, this edict proved to be unenforceable.

Diocletian & the Christians

Aside from the continued problems with finance and border security, Diocletian was concerned with the continuing growth of Christianity, a religion that appealed to both the poor and the rich. The Christians had shown themselves to be a thorn in the side of an emperor since the days of Nero. The problem grew worse as their numbers increased. Diocletian wanted stability and that meant a return to the more traditional gods of Rome, but Christianity prevented this. To most of the emperors who preceded Diocletian, Christians offended the pax deorum or “peace of the gods.” Similarly, since the days of Emperor Augustus, there existed the imperial cult - the deification of the emperor - and Jews and Christians refused to consider any emperor a god.

However, part of the problem also stemmed from Diocletian's ego. He began to consider himself a living god, demanding people prostrate themselves before him and kiss the hem of his robe. He wore a jeweled diadem and sat upon a magnificent, elevated throne. In 297 CE he demanded that all soldiers and members of the administration sacrifice to the gods; those who would not were immediately forced to resign. Next, in 303 CE he ordered the destruction of all churches and Christian texts. All of these edicts were encouraged by Galerius. However, throughout this Great Persecution, the Christians refused to yield and sacrifice to the Roman gods. Leading members of the clergy were arrested and ordered to sacrifice or die and a bishop in Nicomedia who refused was beheaded. Finally, any Christian who refused was tortured and killed. At long last, the persecution came to an end in 305 CE.

Abdication & Death

In 303 CE after his only trip to Rome, Diocletian became seriously ill, eventually forcing him to abdicate the throne in 305 CE and take retirement in his huge palace-fortress in Spalatum (modern-day Split in Croatia). The huge walled complex included colonnaded streets, reception rooms, a temple, a mausoleum, a bathhouse, and extensive gardens. Diocletian also persuaded Maximian to step down as well. This joint abdication enabled Constantius and Galerius to succeed as the new augusti. Maximinus and Severus were appointed as the new Caesars. Although he would briefly come out of retirement in 308 CE, the old emperor remained in his palace raising cabbages until his death in October of 311 CE.

Unfortunately, Diocletian's vision of a tetrarchy would eventually fail. After years of war between successors, Constantius' son Constantine I reunited the empire after the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 CE. He would rule from a city that would one day bear his name, Constantinople. And, in a decision that would have made Diocletian cry out, he gave Christianity the recognition it deserved, even becoming a Christian himself. In 476 CE with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the East, while still bearing some resemblance to the Old Rome, would be reborn as the Byzantine Empire.