The Drake-Norris expedition of April-July 1589 CE, otherwise known as the Don Antonio Expedition, English Armada or Portugal Expedition, was an unsuccessful attempt by a large English naval and army force to destroy the remaining ships of the Spanish Armada of Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE), to reinstate Don Antonio as king of Portugal, and to seize Spanish treasure ships in the Azores. The expedition had a mix of private and state financial backing and was led by Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) and Sir John Norris (aka Norreys, c. 1547-1597 CE), hence its name. Not all parties agreed to the triple aims of the expedition, Drake and Norris ignored the Armada ships, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) was outraged Lisbon had been attacked by land and sea instead, and by the time the English had been beaten off by Spanish forces they were too late to catch the treasure ships. A dismal failure with thousands dead from battle and disease, the English fleet returned home with little to show for their hugely expensive efforts and the Anglo-Spanish war dragged on until 1604 CE.

Multiple Objectives

Following the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 CE which Philip II of Spain had hoped to use to invade England, Elizabeth I wished to push her advantage by destroying those Armada ships which had survived and were now sitting idle in Spanish ports. Elizabeth's premier sea captains had long pushed the ever-cautious queen into taking the war with the Spanish to their own front door. In October 1588 CE, Elizabeth was finally persuaded and invested £49,000 pounds and seven royal ships in a project which mixed state and private funding to assemble a large attack fleet. The captains believed the destruction of Philip's ships, which were being repaired but might be used for another invasion, could force the Spanish king into suing for peace terms. Private investors and the queen, meanwhile, considered the seizure of Spanish treasure ships and possibly one or more of the Azores islands through which they passed as the best return on their investments. Finally, men like Drake and Norris were ambitious for both booty and glory and thought that sacking Lisbon and putting the displaced king Don Antonio back on his throne would lead to a conquest of that country's riches. This mix of interests - necessitated by the English Crown's inability to pay for the entire expedition on its own - led to the expedition having confused aims and was the first link in a chain of events that led only to an empty chest of failure.

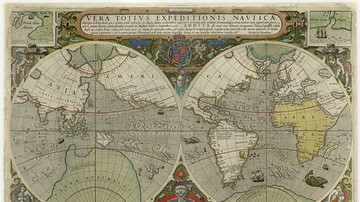

Nevertheless, the English fleet was impressive with 130-150 ships and at least 15,000 men (some historians put the figure as high as 23,000). Indeed, the chance of easy spoils was a major factor in recruitment for the expedition being a huge success, and double the men required volunteered, making the whole thing a much bigger affair than originally intended. These extra numbers would put unbearable strains on the supplies needed for such a large force. Its leaders were equally impressive. Sir Francis Drake was perhaps England's greatest ever mariner up that point in history. He had captured many Spanish ships as a privateer, famously raided Cadiz in 1587 CE, and sent in the fire ships which had so disconcerted the Spanish Armada the year after. On top of all that, Drake had circumnavigated the globe in 1577-80 CE. The mariner, one of the richest men in England thanks to his privateering exploits, sank £5,000 of his own wealth into the project. Sir John Norris, on the other hand, had vast experience of commanding land armies in Ireland, France, and the Netherlands. Norris was an innovator and he organised an English army into regiments for the first time. This seemed like the perfect teaming of admiral and general. Anything other than success for an expedition led by such men was at that point unthinkable.

The fleet, which included many Dutch transport ships, set off for Spain with high hopes in April 1589 CE. The original departure had been intended for February but there were delays in getting troops from the campaigns in the Netherlands. These delays added yet more strain on the logistical requirements of the project. Drake led the flotilla in his favourite flagship, the Revenge, which had done such sterling service against the Spanish Armada the year before.

Corunna

On reaching Spanish waters, Drake ignored his queen's instructions and avoided the identified targets in the Bay of Biscay. The mariner would later claim he had not attacked further east because local weather and sea conditions there would have made it difficult to make a quick escape after a raid. Instead, the easier target of Corunna was attacked over a period of two weeks but it was only partially captured. The well-fortified upper part of the town resisted the assault and the lack of siege artillery in the attacking army proved telling (Elizabeth had baulked at their expense). The English land army then got rather distracted when it came across the town's wine cellars. Looting the lower town, 2,000 Englishmen returned to England more than happy with their efforts and with no concern whatsoever for the wider aims of the expedition. This was the problem of using private and not state armies; as soon as private soldiers found the booty they had joined up for, they considered their involvement in the campaign over.

Meanwhile, 40-50 Spanish ships lay idle and probably defenceless in other Spanish ports further east like San Sebastian and Santander. It is true that the Magdalena peninsula protecting Santander was bristling with five fortresses which is another reason Drake might have shied away from attacking there. Corunna, in contrast, was an easier target but it had been protecting only three Spanish ships (a galleon, carrack, and hulk). It seems clear now with the benefit of hindsight that Drake and Norris were not, in any case, after Armada ships but a much richer if strategically less valuable prize.

Lisbon

The remaining fleet then sailed on to Portugal where an all-out attack was launched on Lisbon contrary to Elizabeth's instructions. The idea to simultaneously attack the fortified city by land and sea was a good one but its execution required excellent timing, troop coordination, and constant communication between the commanders. None of these was evident in the campaign. The first mistake - although not entirely one of the commanders' - was landing the army too far from the city so that they had to march a good way to reach their objective. This meant that the city's defences were alerted to the attack (the raid on Corunna must also have sent alarm bells ringing) and the English soldiers were already fatigued before the fighting had even started.

Crucially, the Portuguese did not rise in support of Don Antonio as hoped for. Lisbon was then governed by a Cardinal Archduke, but his religious beliefs in no way prevented him from forcing the Portuguese inhabitants to help their Spanish overlords keep out the English. The city resisted capture even if some of Lisbon's outer suburbs were taken by the English land army. Lacking sufficient supplies to continue and without much hope of breaking the city's defences, the Lisbon attack was abandoned. The land army was picked up on the River Tagus for a retreat, but as the fleet was becalmed off Lisbon; 21 Spanish ships attacked the invaders, disabling or sinking three English ships. At least Drake managed to then capture a fleet of 60 trading ships which had sailed from Hamburg. These vessels came in use to transport the English wounded back home. Vigo, on the Spanish Atlantic coast, was then attacked, and Drake probably intended to loot more enemy ports but his remaining crews were wracked with disease. In addition, the arrival of storms separated the English fleet and meant Drake had to abandon the Continent.

By now, it was too late to catch the treasure ships coming through the Azores and so the expedition, despite a token effort to take one of the mid-Atlantic islands, finally retreated ignominiously back to England. With a few more minor attacks on Spanish ports on the way home, the Drake-Norris expedition had brought back a paltry £30,000 in plunder and 150 cannons. It was not at all a good return for the price paid in lost men, equipment, and reputation. Visited by war and disease, only some 6,000 men returned to England in July 1589 CE.

Aftermath

The whole sorry episode seriously damaged Drake's reputation and clearly showed that mixing private and state control of an expeditionary force only led to confusion and disunity. The queen was outraged with Drake at the attack on Lisbon, the complete failure to attack the Armada ships, and the poor financial return. The old mariner thus became a landlubber and served as both the mayor of Plymouth and its Member of Parliament. Norris, meanwhile, fought with success in Brittany supporting Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610 CE) against the Spanish and then returned to Ireland to quash the Tyrone rebellion in 1595 CE. The Anglo-Spanish war continued beyond the reigns of both Elizabeth I and Philip II but over the next decade, there would be no more large English expeditions to the Continent as England concentrated on privateering raids on Spanish ships.