The Drownings at Nantes were a series of mass killings that took place in Nantes, France from November 1793 to February 1794 during the Reign of Terror. Overseen by Jean-Baptiste Carrier, the representative-on-mission from Paris, thousands of “counter-revolutionary” prisoners were taken out on barges to the middle of the Loire River where they were sunk.

These mass drownings, or noyades, were at first conducted in secret under the cover of darkness. Consequently, there is little information about how often they occurred, as well as the precise number of victims, a number which could range anywhere between 1,800 and 4,800 with some sources putting the number as high as 10,000. Victims were inhabitants of Nantes’ prisons and were therefore rebels captured during the War in the Vendée, refractory Catholic priests and nuns, and other “suspects” imprisoned under the laws imposed by the Terror. The scale and brutality of this massacre has earned it notoriety as one of the most horrific acts of civilian slaughter to occur during the French Revolution (1789-1799).

Prelude: Nantes & the Vendée

During the time of the Revolution, Nantes was one of the wealthiest cities in France. Situated on the Loire River, about 31 miles from the Atlantic coast, it was a major hub for trade and trans-Atlantic travel. With a population of 90,000, Nantes was second only to Bordeaux in importance on France’s west coast. It was home to wealthy bourgeoisie, merchants, and master craftsmen, and it attracted many countryside peasants looking for work. When the Revolution began in 1789, it was generally welcomed by the Nantais citizens, who showed their support by emulating the Storming of the Bastille and seizing their own local chateau, the Castle of the Dukes of Brittany.

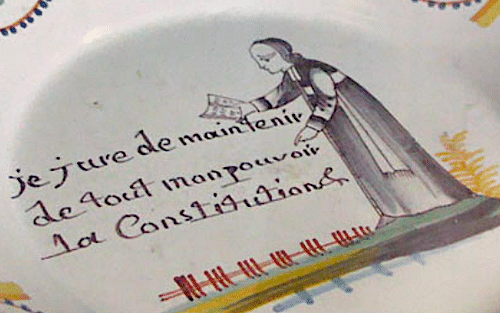

Meanwhile, the rural lands in the region of the Vendée, just south of Nantes, were on average more politically and religiously conservative than the rest of France and bristled under the anti-Catholic reforms imposed by the revolutionaries. Most egregious was the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which outlawed all religious orders and subjected the French Catholic Church to the authority of the state. Clergymen who refused to swear oaths of loyalty to the new constitution were labelled refractory priests and were barred from preaching; by late 1791, such clerics were considered to be counter-revolutionary conspirators and calls went up for their arrests or deportations.

The pious residents of the Vendée saw this as an attack against their way of life and were therefore alienated from the Revolution. When, in February 1793, the National Convention called for 300,000 soldiers to fight in the War of the First Coalition (1792-97), to be raised by conscription if necessary, the Vendeans decided they had had enough. Thousands of peasant uprisings blossomed into a full-fledged rebellion, combining their strength into a unified force that became known as the Catholic and Royal Army. Although the War in the Vendée had not begun with royalist intentions, the rebels made their disdain for the Republic known by acknowledging the claim of Louis XVII of France, the uncrowned boy king still being held captive in Paris.

Under the command of the imposing generalissimo Jacques Cathelineau, the rebels enjoyed initial success. The spring of 1793 saw the entire Vendée region fall to rebel control, and every Republican force sent against them was defeated. Despite his reluctance to give up the home advantage, Cathelineau realized the war must be taken to enemy soil. Rather than striking a blow at Paris itself, Cathelineau instead marched his army to Nantes, which was besieged at the end of June. The wealthy port city would make an excellent prize; not only would it make for a strong provisional capital for the insurrection, but the Vendeans planned to invite a British invasion force into the harbor. With British support, the rebels would have the strength to threaten Paris.

The rebels demanded the immediate surrender of Nantes, lest the garrison be put to the sword. But they had been made over-confident by months of easy victories, and failed to realize that the 10,000-man city garrison was better disciplined and more experienced than any Republican force they had yet encountered. When the garrison refused to surrender, the rebels launched a sloppy, uncoordinated attack on 29 June that ended in disaster when Cathelineau was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter. The massive failure of the Battle of Nantes would mark the beginning of the end of the Catholic and Royal Army, which limped back into the Vendée where it was ruthlessly ground into the dirt by well-equipped and well-trained Republican troops.

As the Republic ravaged the Vendée as punishment for its treason, thousands of Vendean peasants fled the warzone, looking for sanctuary. Many of them arrived outside Nantes, hoping that as non-combatants they would be given refuge. Instead, they were clapped in irons and thrown into the prisons alongside their fathers and brothers who had been captured after the battle and had since been languishing as prisoners-of-war. On 17 September 1793, the quasi-dictatorial Committee of Public Safety enacted the Law of Suspects, which demanded the arrests of all counter-revolutionary “suspects” across France, a term so vague it could be bent to apply to just about anyone. In Nantes and the surrounding lands, those who had aided the Vendean rebels were arrested, as were refractory priests and nuns, and those who were suspected of harboring royalist or Catholic sympathies. By November, the prisons of Nantes were bursting at the seams, with roughly 10,000 people clumped together in small, sordid cells. This was a staggering number, equivalent to more than a tenth of the city’s general population.

Naturally, this put a strain on the city’s resources. Nantes had been made into an immense military hospital, and now had to provide for thousands of wounded Republican troops, all the counter-revolutionary prisoners, and its own population. With winter on the way, the municipal government wrote to the Committee of Public Safety in Paris for help. In answer, the Committee sent a representative-on-mission, Jean-Baptiste Carrier, to Nantes. With him went death.

A Question of Prisoners

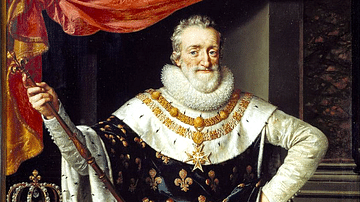

When Carrier first arrived in Nantes, there was nothing about him that would denote a mass murderer. He was born in Yolet, a village in upper Auvergne on 16 March 1756, the son of a tenant farmer. He worked in a law office in Paris until the Revolution broke out, at which time he went back home to sign on with his local National Guard. Carrier was popular enough to be elected to the National Convention in late 1792, where he became a prominent member in both the Cordelier and Jacobin clubs. He voted for the death of Louis XVI of France, and was an enthusiastic supporter of the fall of the Girondins, the Jacobins’ moderate rivals. By September 1793, he had become respected and influential enough to be chosen by the Committee of Public Safety to stabilize Nantes, and to maybe uncover some counter-revolutionaries in the city’s bourgeois government while he was at it.

Carrier arrived in late September and was immediately presented with the issue of a rapidly growing and unsustainable prison population. This problem had to be urgently dealt with for two major reasons: the first was the reasonable fear of contagious disease, such as typhus, breaking out amongst the tightly packed prisoners and spreading to the general population. The second was a concern over the 10,000 counter-revolutionary prisoners staging an uprising, a frightening and disastrous possibility for the city leadership to consider. It was undoubtedly a complicated and stressful conundrum, but it was one that Carrier had to quickly solve. In the words of historian R.R. Palmer, Carrier turned immediately to the most ruthless solution because “ruthlessness seemed to be the easiest way of solving a difficult problem” (220).

On 29 September, Carrier hinted at his intentions in a letter to the Committee of Public Safety, in which he wrote, “I propose…to make up cargoes of unsworn priests now piled up in the prisons, and to give control of them to a mariner from Saint-Servan known for his patriotism” (Palmer, 220). As it turned out, Carrier meant to do exactly that; 160 refractory priests were taken from the prisons and loaded onto a barge anchored in the middle of the Loire, reducing their chance of escape or of spreading disease. While they were not yet drowned, these prisoners suffered horribly from consistent exposure to the elements.

On 7 October, Carrier again reported to the Committee, explaining that the prisons of Nantes were brimming with Vendean partisans. “Instead of amusing myself with giving them a trial,” he said, “I shall send them to their places of residence to be shot. These terrible examples will intimidate the evil wishers” (Palmer, 221). Far from discouraging Carrier from carrying out these proposed extra-judicial killings, the Committee’s reply urged Carrier to, “purge the body politic of the bad humors that circulate it” (ibid). This is precisely what Carrier decided to do; he set about clearing the prisons.

At first, in a fashion consistent with the Terror, he used a guillotine, dispatching the prisoners one by one. This idea was quickly set aside, however; it was much too slow for Carrier’s purposes, and the Nantais citizens had objected to the sight of a public guillotine and its grisly work. Next, Carrier turned to firing squads, carried out by a newly created militia that was dubbed the “Marat Company” after the martyred Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat. Carrier selected a group of 24 “brigands” from the prisons, four of whom were teenagers, to be shot. This was followed two days later by a group of 27.

This continued for some time, although this method, too, proved unsustainable. As one of Carrier’s soldiers reported, “shooting [the prisoners] takes too long and uses too much gunpowder and too many bullets” (Bell, 181). Not wanting to put a strain on the Republic’s available ammunition, it seemed Carrier would have to get creative with his methods of execution. Fortunately for him (and unfortunately for just about everyone else) the Loire was right on his doorstep.

The Noyades

The method of execution with which Carrier would kill thousands was first shown to him by two local revolutionary mariners. Holes would be punched in the sides of flat-bottomed barges, below the waterline, over which wooden planks would be placed to keep the vessels temporarily afloat. Next, the prisoners would be tossed in, bound hand and foot, and the barges would be towed out to the middle of the Loire. Once there, a boatsman would remove or break the planks and quickly jump to one of the accompanying boats, as the barges filled with water. The helpless prisoners were left to squirm and scream as they became submerged beneath the icy river water. Those who managed to break their bonds and try to swim were skewered by the sabers of guards keeping watch on the accompanying boats.

These mass drownings, or noyades, quickly became Carrier's prefered method of execution. Referred to as “republican baptisms” or “the national bath”, it has been proven that at least four instances of these noyades did indeed take place, although the true number is likely much higher; some eyewitnesses place the number at 23. At first, the noyades were conducted secretly in the dead of night, but before long they were being carried out shamelessly in the broad light of day. For weeks after each noyade, the victims' lifeless bodies would wash ashore, half-eaten by fish. These killings were tolerated by the Nantais, primarily because the memory of the Vendean attack on their city was still fresh and also because almost none of the victims were from Nantes. Even as Carrier began overstepping his power by bullying the city itself, the citizens did not try to put a stop to the executions.

Despite the secrecy in which the drownings occurred, the noyades quickly became well-known throughout France, sparking rumors and speculation surrounding the specifics of Carrier’s barbaric atrocities. There were reports of so-called “republican marriages” in which a young man and a young woman, or in some cases a priest and a nun, were stripped naked and tied to one another before being sent off on one of the barges to drown together. There were also reports that Carrier and his cronies would hold “nightly orgies”, forcibly involving women suspects from Nantes’ high society.

At least 1,800 of Nantes’ prisoners were killed on Carrier’s orders between November 1793 and February 1794, all of them without a trial. Some were executed by guillotine or firing squad, but most were drowned. Other sources put this number much higher, to 4,800 or even as many as 10,000, as more prisoners continued to be funneled into Nantes, as if someone were feeding Carrier’s bloodlust. Carrier made sure never to report the specific details of those killed to his superiors, writing to the Committee only that “miracles” were happening on the Loire.

Still, rumors of what Carrier was doing had made their way to Paris, and members of the Committee were disturbed; Georges Couthon reportedly raised his voice and advocated pardoning the Vendean prisoners who he claimed had been misled. Members such as Maximilien Robespierre were concerned that, if the rumors were true, this level of barbarity would turn many against the Republic. To find out for sure what was going on, Robespierre decided to send an agent, the 18-year-old Marc-Antoine Julien into Nantes to report back.

Julien made little comment about the noyades themselves; whether this was because he did not know the extent of them or simply did not care is unknown. But he did make clear his disgust with Carrier’s conduct. On 19 December, he reported that Carrier’s subordinates were terrorizing “true patriots” and were overstepping the limits of power entrusted to them by the Committee. On 1 January 1794, Julien recommended Carrier’s immediate removal, stating that he had refused to recognize the authority of a fellow representative-on-mission, that his underlings were killing, burning, and pillaging with impunity, and that Carrier was deliberately prolonging the War in the Vendée to maintain his own power, having turned Nantes into his own little fiefdom. Only in a final letter sent in February did Julien finally mention the drownings:

I am assured that he had all those who filled the prisons at Nantes taken out indiscriminately, put on boats, and sunk in the Loire. He told me to my face that that was the only way to run a revolution, and he called Prieur of the Marne [a member of the Committee of Public Safety] a fool for thinking of nothing to do with suspects except confine them (Palmer, 223)

Shortly after Julien sent this letter, the Committee recalled Carrier to Paris, although the reasoning for this was probably more to do with him subverting the authority of the Committee and calling one of its members a “fool” than anything to do with the drownings. Carrier begrudgingly obeyed this command and returned to Paris, his authority in Nantes replaced by Prieur of the Marne, the man he had mocked. Although the Terror continued to rage throughout the country, at least in Nantes the noyades were over.

Trial of Carrier

Upon returning to Paris, Carrier was not put on trial or otherwise punished. Some members of the Committee of Public Safety, specifically Couthon and the “Incorruptible” Robespierre were truly disgusted and appalled by Carrier’s reported actions. Yet they could not punish him, for fear of putting into question other acts of violence committed during the Terror that were deemed as necessary evils. Instead, Carrier remained in Paris, without much authority, until the fall of Maximilien Robespierre and his allies on 27-28 July 1794, which marked the end to the Terror.

With the anti-Jacobin Thermidorians in power, Carrier’s position suddenly became rather precarious. Witnesses from Nantes filtered into Paris to denounce him; these witnesses included survivors from the prisons who provided firsthand accounts. Finally possessing evidence, the National Convention had Carrier arrested on 3 September 1794. In November, he was indicted and put on trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal. He defended himself by claiming he had little knowledge of the executions at Nantes, that he had primarily been concerned with securing food and supplies for the wounded soldiers and the city’s population.

Witnesses from both the city and from Carrier’s own “Marat Company” disputed this, providing evidence of Carrier’s involvement in the drownings, as well as other instances of cruelty including thefts, pillaging, the slaughter of women and children, and laying waste to Nantes. Carrier’s characteristic sarcasm did not endear him to the jury, which became horrified by the accusations leveled against him. They unanimously declared him guilty of the mass executions of citizens who had not fought against the Republic, among other crimes. Alongside two of his accomplices, Carrier was sentenced to death and was guillotined on 16 December 1794.