The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was formed in 1602 by the Staten-Generaal (States General) of the then Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. The company was granted a 21-year charter with rights to trade exclusively in Asia and to buy valuable spices, such as nutmeg, mace, and cloves. Spices were in high demand in Europe to flavour food dishes and for use in medicines, and the company eventually gained a monopoly on spices.

By the mid-1600s, the Dutch East India Company had approximately 50,000 employees working in both Asia and the Netherlands. Between 1602 and 1799, when the company was formally dissolved, its ships made nearly 5,000 voyages from the Netherlands to the East Indies in search of sought-after spices and carried over one million people to Asia.

Although the company’s primary purpose was trade, it became a colonial power in 17th-century Asia with the right to make treaties, build fortifications, and conduct military operations. The Dutch East India Company brought an end to the Portuguese monopoly over the spice trade, and at its height, the company’s stock was worth 78 million Dutch guilders (approximately US$ 7.9 trillion).

The Dutch East India Company’s Formation

The Dutch East India Company was a merger between six small, private East India companies in the Netherlands. These merchant companies had been attempting to break into the lucrative spice trade controlled by the Portuguese Empire, but fierce competition between them weakened Dutch efforts to establish a profitable trading network to challenge the Portuguese.

In 1597, one of the six companies (Compagnie van Verre) sent a fleet of four ships to the East Indies under the command of Cornelis de Houtman (1565-1599), a Dutch merchant seaman. It was the first Dutch expedition to the East Indies, and while only 87 of the original 249 crew members survived, the voyage showed that a sea route to the East Indies was possible and that the Dutch could challenge the Portuguese.

Based on de Houtman’s successful voyage and to put an end to private company rivalry, the States Generaal, which was the highest administrative body in the republic, united the six companies into a single joint-stock company. It was granted a 21-year charter on March 20, 1602, with 6.4 million guilders' capital. The company’s name was the United East India Company or Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), known to history as the Dutch East India Company. The VOC was essentially a state-imposed merger between private shipping companies known as voorcompagnie or pre-company.

The VOC’s Operating Structure & Financial System

Six kamers or chambers formed the VOC. These chambers represented the port cities of Amsterdam, Delft, Rotterdam, Zeeland (Middelburg), Hoorn, and Enkhuizen. Each chamber had a board of directors, and the central board or general management was known as the Heeren Zeventien (Gentlemen of Seventeen). Its headquarters was in Amsterdam. The central board consisted of eight directors from Amsterdam, four from Zeeland, and one each from Delft, Rotterdam, Hoorn, and Enkhuizen. The seventeenth director or ‘seat’ rotated among the smaller chambers to counter Amsterdam’s stronger position and also to give them a degree of influence in decision-making.

The VOC took over the fleets of the amalgamated companies, but the six chambers were highly independent, maintaining their own warehouses and offices, equipping ships, and recruiting labour.

The company charter had 46 articles, and Article 10 allowed members of the public to buy shares in the VOC. There were 1,143 investors in the ‘initial public offering’ (IPO) in August 1602. The pre-companies had previously raised their capital from private investors. The VOC is considered the world’s first publicly traded company by opening up to public share issues. Despite the seventeenth director, in reality, Amsterdam maintained its strong position, providing 57% of the total capital of 6.4 million guilders raised.

The VOC charter stipulated that the company would be liquidated after ten years so that capital could be returned to shareholders, who could then choose to reinvest in a successor company. Due to the spectacular commercial success of the VOC in Asia, the States Generaal allowed the VOC to ignore statutory liquidation in July 1612.

The VOC’s ‘revolving’ or back-to-back financial system initially limited the scale of its operations. Each chamber’s cash flow depended on the success of previous expeditions. When ships returned to Europe, the cargo would be sold at a profit, and the earnings reinvested into new voyages. Back-to-back financing was, however, flawed. If a ship was lost at sea or captured by the Portuguese or the demand for spices declined (as it had by the end of the 18th century), the VOC would suffer a cash flow problem.

This problem was understood by Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587-1629), an officer of the VOC and governor-general in Asia for two terms (1619-1623 and 1627-1629). Coen argued that the VOC should be involved in the Asian trade system beyond products meant for the European market and that the company should control key locations (such as the Spice Islands, aka the Moluccas) through military enforcement and permanent outposts.

Some directors of the VOC opposed Coen, but the States Generaal demanded that the VOC arm their ships and carry out military operations to deflect the Portuguese and the increasing threat of the English. In 1609, for example, William Keeling (1577-1619), an East India Company captain, obtained permission to open a fortified trading post in the Banda Islands and purchased nutmeg from the Bandanese.

The VOC had a fleet of around 150 ships, sailing via the Cape of Good Hope to the East Indies and stopping at various ports to obtain spices and other commodities. This meant voyages of up to three years, and crew had to sign on for at least three years, with ships returning in need of expensive repair. It also meant the chambers had to wait longer for returning cargo that could be sold at a profit. The solution was to establish a permanent foothold in Asia, establish solid trade relationships, and negotiate the very best prices.

The VOC Spice Empire

In 1605, a VOC fleet under the command of Admiral Steven Van der Hagen (1563-1621) seized the Portuguese fort (Fortaleza Nossa Senhora da Annunciad) at Ambon in the Spice Islands. The Dutch renamed it Kasteel Victoria, and it became the main base and entrepôt (trading centre) of the VOC in Asia until 1619.

This strategic move secured a monopoly of the clove trade because Ambon was a key point on the Eurasian trade route. Soldiers were stationed at the fort, and treaties were signed with local rulers to ensure the monopoly. Frederick de Houtman (1571-1627) was appointed the VOC’s first governor-general (1605-1611). He was the brother of Cornelis de Houtman, and in 1618, while sailing on the company ship the Dordrecht, a section of the west coast of Australia was accidentally discovered.

Batavia (present-day Jakarta) became the VOC’s main administrative centre and warehouse in 1619. It remained the capital of the colonial Dutch East Indies until 1942 when the Japanese expelled the Dutch and changed the name to Djakarta. Jan Pieterszoon Coen saw the need for an eastern headquarters for the VOC and a permanent administrative centre where goods could be stored and sent back to Europe. Coen believed that force was necessary to expand the VOC’s influence. He arrived with 17 ships and 1,000 soldiers in May 1619 and attacked the kingdoms of Banten and Jayakarta before burning the city of Jayakarta and building Batavia on the city’s ruins.

Coen was a harsh administrator, and his strategy was to capture the Banda Islands and secure a monopoly on nutmeg and mace. In 1621, with a fleet of 13 ships, Coen, with 1655 soldiers and 250 Japanese mercenaries, landed on Lontor (present-day Banda Besar), the largest of the Banda Islands. They set fire to Bandanese homes and killed more than 10,000 Bandanese, or more than 90% of the population (although figures vary). This act is known as the Banda Massacre.

In May 1621, 44 Orang Kaya (local leaders) were killed, and any Bandanese who were captured or had escaped were sold into slavery. The cultivation of nutmeg in the Banda Islands would, therefore, require the importation of slave labour from Java. The Dutch East India Company now had a monopoly over nutmeg and mace production, and until around 1760, the annual profit for the company was six million guilders.

By developing an extensive intra-Asian trading network, the VOC’s spice empire extended to:

- Ceylon (Sri Lanka). In 1638, the company took control of the port town of Galle on the island’s western side and the region’s cinnamon plantations. VOC administrators settled in Colombo and exported 8,000-10,000 cinnamon bales annually.

- Formosa (Taiwan). Between 1624 and 1662, the VOC maintained a settlement at Fort Zeelandia, which became the base for company trade in the South China Sea. The Dutch became involved in trading raw silk, silver, and gold.

- Vietnam. A trading post in Hoi An was established in 1633 when the Trinh rulers granted the VOC trading privileges. There was increasing demand for Tonkinese silk from northern Vietnam.

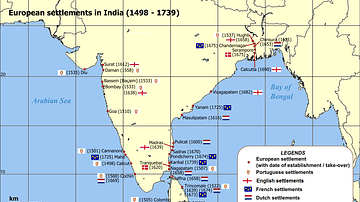

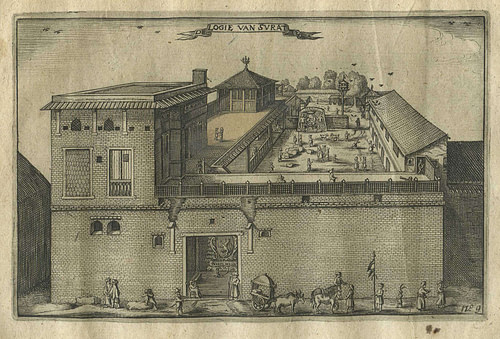

- India. The VOC started trading in India in 1604 and built a factory in Pulicat (Pazhaverkadu) on the Coromandel Coast of southeast India. Further stations were established in Surat, Bengal, Malabar Coast, and Konkan and saw the Dutch trading in silk, indigo, and a calico fabric highly prized by Dutch women.

- Siam (Thailand). The company’s main presence was in Ayutthaya. King Ekathotsarot (1560-1610) granted land to the VOC in 1606. The Dutch built a factory there, gathering Siamese goods such as deerskins, buffalo horns, cowhides, and gumlac, which would be sold in Japan.

- Japan. The Tokugawa shogunate or military government (1603-1867) restricted the VOC’s activities to Dejima, a small island in Nagasaki harbour. Dejima was an artificial island constructed for the Portuguese, but the shogunate expelled foreigners under its isolationist policy. The Dutch, however, were permitted to remain but were moved to Dejima in 1641. The Dutch introduced telescopes and microscopes to the Japanese, while the sale of Tonkinese silks resulted in a profit of 710,000 guilders for the VOC.

VOC Explorations

The VOC was always looking for trading opportunities, leading it into uncharted waters. The two major voyages were those of Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659) and Willem de Vlamingh (1640-1698). Abel Tasman became a sea captain with the Dutch East India Company in 1634. The governor-general at Batavia, Anthony van Diemen (1593-1645), wanted to expand the Dutch influence in Asia. The VOC was also interested in the search for gold and silver and a sea passage across the Pacific to Chile.

Abel Tasman commanded the Heemskerck and Zeehaen, setting sail from Batavia in August 1642 to look for the undiscovered southern land (Terra Australis Incognita). By November, he sighted the west coast of Tasmania, an island state off mainland Australia that the explorer christened Van Diemen’s Land. Sailing eastward, Tasman sighted New Zealand’s South Island.

Willem de Vlamingh was sent in 1696 to search for two VOC ships, Ridderschap van Holland (Knighthood of Holland), which had gone missing on its way to Batavia in 1694, and Vergulde Draeck (Gilt Dragon), lost in 1656. He was also instructed to chart parts of the western coast of New Holland not previously mapped by the Dutch. Although no trace of the VOC ships was found, de Vlamingh and his crew mapped 1,500 kilometres (932 mi) of coastline, landed on Rottnest Island, and ventured up the Swan River, becoming the first Europeans to sight the Western Australian black swan.

The VOC lost interest in Australia. They sent their last ships, the Rijder and the Buis, to the Australian continent in 1756 to explore the Gulf of Carpentaria (northern Australia). Although Tasman and de Vlamingh’s voyages brought no rewards in trade, the VOC played an important role in the exploration and charting of Australia long before Captain James Cook (1728-1779) stepped foot on the foreshore of Botany Bay in 1770.

The Decline of the Dutch East India Company

The VOC has been likened to a modern corporation due to its board of directors, publically traded shares, and global reach. It was a company that maintained its own army, minted its own currency, negotiated treaties, and acted like a colonial state. Yet, by the late 18th century, the Dutch East India Company was bankrupt, and the government formally dissolved the VOC on December 31, 1799.

High administrative costs. The VOC had to employ military officers, soldiers, and employees at great expense to maintain its trading monopoly. In 1766, for example, it cost 12.2 million guilders to pay for the military.

Corruption. Company officials working in Asia would conduct illegal trade or line their pockets. The governor-general’s annual salary was 14,000 guilders, but Joan van Hoorn (1653-1711), who was governor-general for five years from 1704 to 1709, returned home with ten million guilders.

Rivalry & Conflict. The Dutch clashed with the English and the British East India Company (EIC) as the EIC established their own trading posts in Asia. In 1623, the Dutch in Amboyna (present-day Ambon) tried and executed ten Englishmen, nine Japanese, and a Portuguese trader after they confessed, under torture, to treason and a plot to seize the Dutch fortress and assassinate the governor-general. This incident, known as the Amboyna Massacre, ultimately helped fuel the Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652-1784) – the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War saw the British Navy destroy the Dutch fleet, and its routes between Asia and Europe were severely disrupted in 1780. Although the Dutch relentlessly eliminated foreign competitors from the Spice Islands, it came at an economic cost. The VOC also became involved in financially draining local politics, particularly the Javanese wars of succession (1703-1755).

Spices were no longer in high demand. Other goods such as tea, coffee, and sugar broadened the international market and rivalled spices in economic importance. New foods and preparation styles emerged, making spices no longer a desired luxury item. Similarly, smuggling resulted in plants and seeds being cultivated elsewhere. Nutmeg, which was originally from the Spice Islands, found its way to the Caribbean, and the English took cloves and nutmeg from southeast Asia to India.

VOC legacy

The Dutch East India Company – a company that existed for nearly 200 years – was more than a trading company. The VOC revolutionised long-distance trade, connected the East with the West through an efficient supply chain that shipped spices, porcelain, textiles, and other commodities, and became a colonial force in Asia.