The Early Joseon Period (1392 - c. 1550 CE) in Korea was bookended by internal power struggles but witnessed major scientific and societal advances and prosperity. The Joseon (Choson) Dynasty ruled Korea from 1392 CE to 1897 CE, and scholars typically break this 500-year dynasty into three periods: the Early Joseon, the Middle Joseon, and the Late Joseon periods. This period in Korean history saw great strides in science, culture, literature, and education; long periods of peace peppered with invasions from neighboring China and Japan; and isolationist policies from the 18th through the 19th century CE.

Beginnings of Joseon Korea

In the last few years of the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392 CE), King U (r. 1374-1388 CE) asked general Yi Seong-Gye to lead an invasion of the Ming Dynasty's territory northwest of Korea, in present-day Liaoning China. Yi, who had been in opposition to the invasion from the start, marched back from the Yalu river border of Goryeo and Ming as soon as he reached it and staged a coup to overthrow King U and his successor King Chang (r. 1388-1399 CE).

Yi Seong-Gye and his supporters killed King Chang to install King Gongyang, a descendent of the 12th-century CE King Sinjong (r. 1197-1204 CE). However, Gongyang only acted as a puppet for Yi Seong-Gye to rule through between 1389 and 1392 CE when he finally assumed control of the throne for himself. Yi then exiled Gongyang and named his dynasty Joseon, after the ancient Gojoseon state (2333-108 BCE), adopting the name King Taejo (r. 1392-1398 CE).

First Joseon Years

One of the first acts Taejo made as king was to move the Korean capital from Kaesong in present-day North Korea to Hanyang (present-day Seoul, South Korea). The moving of capitals at the start of a new Korean dynasty was a tradition.

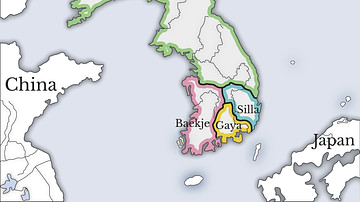

The first few kings of Joseon moved quickly to expand the borders and fortify the land. Invasions of Mongols in the north and wako pirates from Japan on the coasts of the Korean peninsula marked the final decades of Goryeo and the first decades of Joseon. Joseon kings took advantage of the receding Mongols to claim and fortify land in the north, and Sejong the Great (r. 1418-1450 CE) invaded the wako pirates' primary base of Tsushima island to reduce their attacks.

Internal struggles also marked the early years of Joseon, namely between Taejo's sons. After becoming king, Taejo moved to decide which of his sons he would name as heir. This brought about the Strife of Princes, where his sons raised their own armies and fought to be their father's heir. After one son was killed in combat and Taejo's wife died suddenly, Taejo named his son Yi Bang-Gwa (King Jeongjong, r. 1398-1400 CE) as heir and abdicated to mourn in 1398 CE. A second Strife of Princes took place in 1400 CE, and Jeongjong named his brother Bang-Won heir before quickly abdicating. Bang-Won became King Taejong (r. 1400-1418 CE), ruling for 18 years before passing the throne to his son King Sejong the Great. Sejong brought about a much-needed period of stability and peace and ushered in advances in all walks of Korean life.

Sejong Era

King Sejong ruled from 1418 to 1450 CE and had a profound impact on the young Joseon kingdom. Under his reign, Korea made advancements in medicine, science, law, literature, and culture. While his greatest achievement was the personal creation of the Korean alphabet, Hangul, he also brought in Confucian ideals from China and institutionalized them within Korean society and government.

However, shortly after Sejong's death and the death of his successor, King Munjong (r. 1450-1452 CE), Sejong's grandson King Danjong (r. 1452-1455 CE) assumed the throne at age 12. Before his death and knowing his son Munjong was too ill to rule very long, Sejong had instructed scholars and councilors to help Danjong rule before he came of age. With the power of the king minimized, Danjong's uncle, Sejo, usurped the throne by forcing Danjong to abdicate and then exiled Munjong in 1455 CE.

Sejo Era & Three Literati Purges

Sejo's rule (1455-1468 CE), however, was looked down on by government officials "as a violation of Confucian ethics" given that he forcibly took the throne from his nephew (Kim, 190). This led to an assassination attempt of Sejo by six members of Sejong's Hall of Worthies (Jiphyeonjeon). Sejo discovered their plan and executed some while others went into hiding. This event became known as the Sayuksin or Six Martyred Ministers. These six ministers would become idolized in later Joseon periods when other former officials, known as the sarim, who were not part of the assassination plan came to dominate politics as government officials.

After a period of prosperity under Sejo's successors, tyranny arrived with King Yeonsangun (r. 1494-1506 CE). Yeonsangun killed members of the sarim when they opposed some of his decisions, which became known as the First Literati Purge in 1494 CE. He committed a second purge in 1504 CE after he learned that his birth mother had been executed in 1482 CE. The term 'literati' in this era of Korean history refers to officials who adhered to Confucian doctrine and wanted to cultivate virtue and ethics in the political classes. These beliefs were opposed by officials whose families had been in power for multiple generations and who wanted to keep a close hold on government seats.

Throughout the 1500s CE, two more literati purges would take place. The Third Literati Purge occurred in 1519 CE under King Jungjong (r. 1506-1544 CE) when the hungu faction of government officials, who had held power for many years, became wary of the new sarim scholars' power, led by Jo Gwang-Jo. Even though Jo Gwang-Jo was the most trusted advisor to Jungjong, the hungu scholars successfully convinced the king that Jo's supporters were planning a coup. Jungjong had Jo and a few other sarim killed, much to the opposition of most government officials and the populace. After Jo's death, many sarim went into hiding or exile.

Royal Infighting & the Fourth Purge

Jungjong's death in 1544 CE brought about political infighting for the throne. Jungjong's two sons, each from different women, and their relatives fought for the throne. Each family identified with a different political faction, much like the sarim and hungu. First, Jungjong's eldest son Injong became king in 1544 CE when Jungjong died. Injong (r. 1544-1545 CE) and his family, notably his uncle Yun Im, were of the taeyun faction who closely associated with Jo Gwang-Jo and the sarim.

However, their success was short-lived as Injong died a year later in 1545 CE, leading Jungjong's younger son Myeongjong and his family to win the throne. As Myeongjong (r. 1545-1567 CE) was 12 years old when he took power, his mother and uncle, Yun Won Hyung, ruled for him. The soyun faction then killed Yun Im and many other taeyun officials in the Fourth Literati Purge, ensuring their faction could rule with less opposition from Neo-Confucian ministers. The theme of these purges, as Jinwung Kim states, "was the struggle for power between the meritorious elite and the Neo-Confucian Literati" (224).

After relative stability in the beginnings of the Joseon Period and successful implementation of Confucian philosophy by Sejong in the early 15th century CE, the strive to keep Confucian ideals at the heart of Korean political decision-making by the sarim and taeyun factions led to Purges and political instability. The Middle Joseon Period was marked by further political troubles, Japanese invasions of Korea known as the Imjin Wars (1592-1598 CE), the Jin invasion (1627 CE), and the Qing invasion (1636 CE). These led to the isolationist policies and resurgence of progress in the Late Joseon Period.

Military Structure

Before Joseon's founding, each royal family member commanded their own personal armies. In 1400 CE, however, Taejong banned private armies and transitioned to a national army. The organization of the national army was similar to the Korean Army's organization today: a combination of conscripts for infantry and supporting personnel; and professional military members to serve as officers and for specialized defense. Conscription required all men living in Joseon Korea to serve for 2-3 months every year. Service call-ups were rotational so that the military was always fully staffed. When called, men served their 2-3 months then went home while another group of men served. Professional military members defended Seoul and the palaces. Officers were also drawn from professional ranks, with grade determined by their score on a military skills and aptitude test. The military divided Korea into 5 regions, with each region having one army and one navy garrison. Some regions had more than one garrison during times of trouble.

Foreign Policy

The early Joseon Period, especially after the Gihae Expansion of 1419 CE, was relatively calm. This allowed Joseon to strengthen its relationship with the neighboring Ming Dynasty of China. Joseon kings attempted to 'Sinicize' Korea by bringing in Chinese ideas and philosophy, especially Confucianism. Joseon kings held great respect for Ming China and often sent envoys to China on the New Year, and even asked Ming rulers to confirm their status as king once coroneted in Korea.

Relations with Japan were more strained. Wars with the Japanese marked the beginning and end of the Early Joseon Period, and between these wars, Japanese pirates continued to raid coastal Korean cities. After the Gihae Expansion, Joseon allowed limited trading privileges with Japan. Jinwung Kim notes that "the number of Japanese ships that might trade with Joseon was set at 50 each year, and the ships were permitted to port only upon presenting credentials issued by the lord of Tsushima" (210).

Economy & Trade

The Early Joseon Dynasty continued the Goryeo Dynasty's method of employing skilled workers in the government as opposed to forming private enterprises. Crafters, tailors, cooks, and more worked for the government for most of the year but could respond to private orders as long as they paid a special tax to the government for that work. This government-sponsored industry helped develop Seoul as the center of the Joseon-era economy.

King Taejong attempted to monopolize trade and commerce within the cities and large towns by owning shops on major roads and leasing them to merchants and traders while still imposing a tax on their sales and forcing them to sell only pre-determined wares. Soon enough, peasants began organizing their own sporadic markets not backed by the government in order to sell necessities and equipment. Even though the government attempted to shut down these sites, they persisted nonetheless.

The major forms of currency in the early Joseon years were grain, silk, and cloth. As the barter system dominated, cloth played an especially important role. King Sejong and his successors attempted to make coinage the major form of currency. The spread of coinage was slow, however, only becoming widespread in the late 18th century CE. Consistent coin minting only occurred after 1678 CE, when the mint issued sangpyeong tongbo copper coins.

Religion in Early Joseon

The early Joseon kings, notably Sejong, strived to implement Confucian ideals into all parts of Korean society. Sejong banned Buddhism in favor of Confucianism and ruled under Confucian beliefs. These ideals called for the general population to respect the kings and other law-makers, but it also demanded that kings rule for the betterment of society and that they follow their own laws as well.

While Confucian ideals led early kings to be relatively selfless and well-liked, it came at the expense of women's place in society. As Jinwung Kim writes:

As time went on, women were increasingly relegated to the category of the so-called naeja, or "inside people," who devoted themselves to the domestic chores of child rearing and housekeeping (Jinwung Kim, 186-7).

Even though Korea's Neo-Confucian society was built around villages following their leaders, the country following their king, and the king making decisions to move the people forward, women gradually saw their place in society take on a supporting role to the men who ran Joseon Korea.

The establishment of Confucianism in Joseon also led to the political factions and infighting. Opposing factions had differing beliefs about who should be able to become a government official, with Neo-Confucian factions arguing that any person, no matter their class at birth, should be able to become an official if they had the proper skills. Sejong the Great emphasized this with his discovery and appointment of a peasant, Jang Yeong-Sil, as a key scientist in the Hall of Worthies. Later in the dynasty, Yi Sang-Jwa, who was born a slave, was appointed as a government painter after being recognized for his artistic talent.

Society & Science in Early Joseon

While the civil service entrance exam, the Gwageo, had been around in the Goryeo Dynasty, the first Joseon kings placed more emphasis on the exam and revamped the materials. First, students needed to pass qualifying exams on the Four Books and Five Classics of China, and composition of prose and poetry in a Classical Chinese style. Those who passed the qualifying exams took the final exam, Mun-Gwa. The final exam consisted of three parts, whittling the group down to 33 students. These students then took the Jeonsi palace exam, which the king presided over. Their scores ranked the students to determine what level of office they would hold. While any Korean could take the exam, the time and literacy requirements all but restricted the exam to the upper classes of society.

Social mobility in the Early Joseon Period was much greater than in the Goryeo Dynasty. Koreans were free to move up the class hierarchy, and some even did so at the beckoning of the king, like Jang Yeong-Sil. Those who had the means to study for and pass the civil service entrance exams were given cherished seats in the government, which then helped their children earn the same posts. Progressive taxes introduced by Sejong, based on crop production instead of flat taxes, and handbooks that cultivated the knowledge from all over the kingdom helped farmers prosper. Sejong also gave farmland to some of the lowest classes of society in an effort to integrate them into society. Slaves, however, were still owned and traded amongst their owners, and their children were born into slavery.

From a scientific standpoint, the Early Joseon Period, most notably the era of Sejong, saw substantial progress in areas such as timekeeping, geography, and astronomy, among others. Korea's first water clock was invented, allowing for exact timekeeping. Sejong ordered precise maps of the Joseon territory, which are exceptionally accurate even today. Astronomical measurements made strides through a new facility at the king's palace, and these led to the design of a new calendar.

Art & Architecture

As the era progressed, Joseon art diverged from Chinese art to develop its own tradition and style. Calligraphy, painting, and poetry dominated the Confucian Joseon art forms, with poetry being one of the most important. Students taking the civil service entrance exam were required to compose poetry at a high level, and anthologies of poetry starting from the Three Kingdoms Period up through the Goryeo Dynasty.

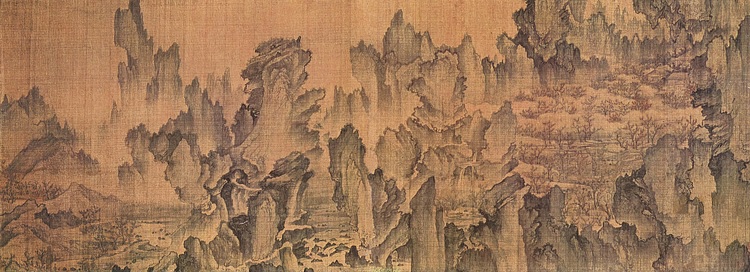

Paintings of the Early Joseon Period were primarily landscapes. Fictional landscapes, the norm in China, were popular in the beginning. This changed quickly, however, as artists painted real landscapes in great detail. However, one of the most famous landscape paintings of the period is presumed to be a rendition of one of King Sejong's son's dreams (Mongyudowondo by An Gyeon).

Porcelain developed new styles in the Early Joseon Period compared to the preceding Goryeo. Puncheong porcelain, blue-green pieces as opposed to the celadon ones from Goryeo, became prevalent early on. A short time after puncheong porcelain, paekcha porcelain became widespread. Paekcha porcelain was white and prized for its relative simplicity.

Architecture in the Early Joseon Period also followed Confucian ideals like other aspects of society and art. Practicality and harmony with nature were important to architects. Seoul was a major center of architecture in the early Joseon years after the capital moved from Kaesong. Early kings built the Five Grand Palaces - Chankdeok, Changgyeong, Deoksu, Gyeongbuk, and Gyeonghui. Gyeongbuk Palace is the largest of the five and acted as the home of the kings and seat of the government.

Besides palaces, gates were a key form of architecture. Seoul's city walls had eight gates, six of which still stand today, although Namdaemun Gate burned in a 2008 CE fire (reopened 2013 CE) and four of the others have been rebuilt in modern times. Sukjeongmun is the only one still standing in its original form and was rarely used in the Joseon era.

Legacy of the Early Joseon

The Early Joseon Period began and ended with internal power struggles. In between these, however, were periods of significant progress and a relative absence of external war. The Early Joseon Period saw the establishment of Confucianism, leading to almost 50 years of steady progress and stability. After this period of stability, constant struggles for both the throne and for political power in the government through factions led to stagnation and literati purges. The Early Joseon Period ushered in the Middle Joseon Period which saw external wars, but the progress made in the early to mid-1400s CE was revived in the Late Joseon Period from the 1700s to 1900 CE.