Easter is the Christian holiday that celebrates the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth three days after he died from crucifixion by the Roman magistrate Pontius Pilate (c. 30 CE). Easter Sunday is the culmination of the week-long events that preceded his death, re-enacted every year in liturgical ceremonies known as Easter Week. The word, 'Easter' may have derived from the work of St. Bede the Venerable (672-745 CE) who wrote a history of the conversion to Christianity by the Anglo-Saxons in Britain (Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum). In his writings on the calendar, he claimed that Eostre, an Anglo-Saxon and German fertility goddess, was the local term for the month of April. Eostre celebrated the renewal of fertility each spring, with symbols that included eggs and rabbits (both ancient concepts of fertility and renewal of the cycles of life).

Historical Context

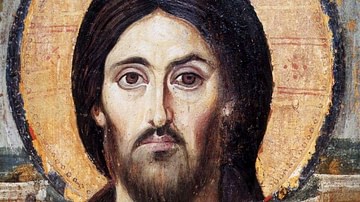

Beginning with the gospel of Mark (c. 70 CE), all the gospels relate the suffering and death of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish prophet who proclaimed that the God of Israel would soon establish his rule on earth. Pesach in Hebrew, pascha in Greek, was one of the three mandatory pilgrimage festivals in ancient Judaism. Passover re-enacted the story of the Jews' slavery in Egypt when God delivered them from the oppression of Pharaoh (as related in Exodus 12). As the tenth and final plague on Egypt, God would send the angel of death among the Egyptians "to kill the first-born of Egypt." To protect the Hebrews, they were to slaughter a lamb and place its blood upon their doors. Exodus contained the command that the Hebrews were to re-enact and celebrate this event each year. The lamb was to be slaughtered on the 14th day of the month of Nisan and eaten on the 15th. Jews followed a lunar calendar, so it did not always fall on the same day every year.

It was during this festival that Jesus was executed by Rome. After his death, his body was placed in a nearby tomb. His women followers went to the tomb on Sunday morning, only to find his body gone. His followers proclaimed that he had been raised from the dead by God. This central event of resurrection was celebrated as the most important event in the life of Jesus. Christmas was not celebrated until after the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine I in 312 CE.

The followers of Jesus took his message to the towns and cities of the Eastern Roman Empire, where Gentiles (non-Jews) soon outnumbered the Jewish followers. For Gentiles, the story of a dying and rising god would have sounded quite familiar. There were native cults known as “mystery cults” that required secret initiation rituals. The major ones were centered on gods and goddesses, such as Demeter and Dionysos, who had suffered death but then were resurrected to life again.

Date of Easter

One of our earliest writings concerning Easter comes from Melito (d. 180 CE) who was the Bishop of Sardis in Western Turkey. He wrote a homily, On the Pascha, which was delivered sometime between 160 and 170 CE. Melito combined the traditions of Judaism with his education in Greek philosophy in his discussions of both the life of Jesus and the understanding of Jesus' role in the universe. With no central authority, one of the earliest disagreements was when to celebrate Easter. This is what came to be called the Quartodeciman controversy (Latin for '14th'). Should the followers of Jesus celebrate the event on the 14th of Nisan like the Jews, or should they have their own distinct practice?

Melito proposed that the celebration should follow the Jewish practice of Passover on the 14th of Nisan, which was apparently the practice in Asia Province (modern-day Turkey). This went against the teaching and the practice in Alexandria and particularly Rome. Bishop Victor of Rome (d. 199 CE) had refused to follow Jewish practices and tried to excommunicate those bishops who disagreed with him. Several meetings were held on the issue, but disagreement among the churches continued until the Council of Nicaea, called by Constantine the Great in 325 BCE. It was then decided that Easter should be celebrated independent of Jewish reckoning and that it should take place on the same date throughout the Roman Empire and always fall on a Sunday. Constantine recommended that the church follow the practices in Rome and Alexandria.

For millennia, Egyptians had followed a solar calendar which also observed the spring and fall equinoxes. This type of calculation was adopted by Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) for Rome in the 1st century BCE. It took time and several conferences to establish conformity in the Roman Empire. Christian missionaries traveling to Britain and Ireland encountered different calculations. In 1582 CE, the Catholic Church in the west adopted the Gregorian calendar under the leadership of Pope Gregory XIII. This determined a solar year of 365.2425 days, with adjustments made every four years. Ultimately, Western Christianity adopted the determination that is utilized today: Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox and so sometimes Easter coincides with the Jewish Passover and sometimes not. Many of the Eastern Orthodox churches retain the Julian calendar, which determines a different date.

Lent

Lent is observed 40 days before Easter through prayer, penance, charity, and self-denial. One of the purposes is to help the participant identify with the sufferings of Jesus. The origins of this practice are unknown, although theories include its introduction at the Council of Nicaea as well as Jewish traditions of fasting as a ritual of atonement (such as on Yom Kippur). Ultimately, it was also related to the temptations of Jesus in the wilderness (40 days and nights).

Preceding the Lenten season is Shrove Tuesday. 'Shrove' comes from the word for 'absolve' and one should be shriven of past sins before Lent begins. On Shrove Tuesday, the practice developed of ridding the house of eggs, fat, and butter, considered luxuries that should be given up during Lent. Hence, many cultures developed specific recipes that used these items, specifically in pancakes, and hence the French term Mardi Gras ("Fat Tuesday"). In many countries, this day includes parades with masked characters, singing, and dancing. The revelry is understood as one last extreme before the next 40 days of self-denial.

Lent begins on Ash Wednesday. A day of fasting, the ash element is derived from the ancient Jewish concept of ashes as a sign of mourning. The origins of this practice are not exact, but we know that by the 2nd century CE, Bishop Tertullian (160-225 CE) claimed that confession of sin should be marked by lying in sackcloth and ashes. The scriptural texts read on this day include Genesis 3:19:

By the sweat of your bow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.

The gospel reading is taken from Matthew 6:16-21:

And whenever you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces so as to show others that they are fasting . . . But when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may be seen not by others but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

This reading and ritual do, however, appear to go beyond the original intent of the passage. Believers are physically marked with ashes on their foreheads.

Easter Liturgy

Through the centuries, an Easter liturgy was developed in the churches as both a memorial to the events and a re-enactment. The form of the liturgy is taken from the gospel story known as the Passion Narrative (from Latin for 'suffering'), highlighting the suffering and torture of Jesus during the last days of his life on earth. Passion week begins on the Sunday before Easter and is a re-enactment of Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem when the people welcomed Jesus as the descendant of King David by cutting palm branches from trees and waving them while reciting elements from Jewish Psalms. Participants are given palm branches and process throughout the church.

Maundy Thursday (from the Latin 'commandment') is also known as Holy Thursday and recognizes a story only found in the fourth gospel of John when Jesus ordered a new commandment to demonstrate love, the 'washing of the feet' ritual. It also celebrates the original setting for what is known as the Last Supper. This is when Jesus instituted the words of what eventually became the communion ritual. From the evidence of Paul's letters, this re-enactment (meeting to remember the Lord) was one of the earliest Christian rituals. Eventually, this ritual became the center of the mass, the weekly celebration of the churches.

The Catholic churches teach that the institution of these words by a priest literally transforms the bread and wine into the “body and blood of Jesus.” The Protestant Reformation rejected this idea but continues to re-enact the ritual as symbolic representations only. Many modern churches incorporate both the last supper as well as foot-washing rituals into the Holy Thursday liturgy. Select people are chosen to have their feet washed by the minister, and these often include the homeless and indigent.

Good Friday/The Via Dolorosa (“Sorrowful Way”)

In the Middle Ages, a formalized ritual was developed in Jerusalem which became the norm in Catholic communities. During the Byzantine era, sites in the city associated with Passion Week began to be identified and processions were led by believers who marked each event. The procession ended at the traditional site of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the tomb of Jesus.

Other sites include the Antonia Fortress where Jesus was condemned by Pilate, the cells where he was flogged, and the sites where he allegedly fell during his ordeal. Pilgrims in Jerusalem continue to walk this route, particularly on Good Friday. In the 14th century CE, the re-enactment of the events was transposed to churches all over the world in a ritual that is termed The Stations of the Cross. Catholic Churches have pictures lined on the walls inside the building indicating each event. During the Lenten season, the faithful attended services on Friday evenings, stopping at each site while praying with a rosary, a string of beads that developed from early monastics use of knotted ropes to keep track of prayers.

In Catholic churches on Good Friday afternoon, the entire Passion Narrative is usually read by the ministers and congregations. In the 7th century CE, the Vatican adopted a ritual practiced in Jerusalem where a piece of the True Cross was venerated on this day. A large form of a crucifix with the body of Jesus is uncovered and participants kneel and kiss the wounds and feet. Protestant denominations do not include the body of Jesus on their crosses.

Holy Saturday

Holy Saturday recognizes the time that Jesus was in the tomb. By Late Antiquity and through the Middle Ages, literature evolved that became known as The Harrowing of Hell. 'Harrowing' was an Anglo-Saxon term for raiding, such as Viking raids, and the tradition claimed that on Saturday, Jesus went to Hades and fought with the Devil to retrieve the souls of the righteous. Apparently, there had been concerns about the salvation of some ancient people who had lived before the manifestation of Christ on earth. The Harrowing of Hell claimed that Christ's victory over the Devil meant that when he arose from the dead Sunday morning, the souls of the righteous emerged with him. This included Adam, Noah, Abraham (the patriarchs of Israel), and the Prophets. At the same time, Socrates, Plato and other philosophers were saved as well.

In the Orthodox traditions, Holy Saturday is marked by the Easter vigil at midnight. In the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, the Greek Patriarch gathers with believers at the tomb of Jesus. The Patriarch enters the tomb and emerges with a miraculously lit candle, and proceeds to light everyone else's in the crowd. With candles symbolic of resurrection, everyone then processes around the church, chanting hymns.

Easter Sunday

Easter Sunday celebrates the finding of the empty tomb and the angels' declarations that he is risen. Many churches have sunrise services outdoors rather than the traditional celebration in the churches.

Pentecost

Originally a Jewish festival, the "feast of weeks", Pentecost was a secondary agricultural festival in the spring. Pente meaning 50, it began on the sundown of the 49th day after Passover. The Christian story of Pentecost is found in Acts 2 when the spirit descended upon the disciples in Jerusalem with fire. Jews who were present in the city heard their voices "in their own tongues". It resembles a similar story when Moses brought down the commandments to the elders at Sinai. Christian tradition then claimed that this event was God issuing a new covenant for the followers of Jesus. It is therefore often referred to as the birthday of the church.

Easter services conclude 40 days after Easter on Ascension Day when Luke reported that Jesus ascended into heaven. The site is associated with the top of the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

Easter Customs

Easter Eggs & Egg Hunts

Over the centuries, several cultural customs were added to the celebration of Easter. These reflect both ancient concepts as well as local beliefs wherever Christianity became dominant. Throughout the ancient Mediterranean Basin, eggs were a symbol of fertility and new life. In Etruscan tomb paintings, people are often seen holding an egg, and thus it is a symbol of an afterlife. In Africa, Sumer, and ancient Egypt, ostrich eggs were painted, engraved, and placed in tombs. There are several theories as to how Christians began utilizing the egg as a symbol, but one source claims the Christians of Mesopotamia dyed eggs red for the blood of Jesus. The emergence of a chick from an egg also symbolized the empty tomb from which Jesus emerged.

The Orthodox communities, particularly famous for Easter egg decorations, translated the custom through the Balkans and into Russia. In Western Europe, we know that in the 17th century CE, Rome had originated a special blessing on eggs as part of the Easter ritual. At the same time, the ban on eggs during Lent would have produced a surplus of eggs that had to be boiled to at least preserve them for a time. However, most theories of the association of eggs with Easter in Europe relate it to the local beliefs concerning the goddess Eostre as the egg was one of her symbols. Catholic and Protestant communities brought the tradition to the Americas during the colonial period.

Many countries developed the idea of an Easter egg hunt, which is particularly aimed at including children in the game. One theory is that it reflects the hunt for matzoh by Jews at Passover, but this remains speculative. In the United States, a major Easter egg hunt is conducted by the presidential family on the lawn of the White House.

Easter eggs have evolved most popularly to consist of chocolate. The first attestation of this practice appeared at the court of Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715 CE). Modern plastic versions contain jelly beans or other small candies.

The Easter Bunny

Most agree that the character of the Easter Bunny originated in Germany and was then brought to America by Protestant immigrants. It was first attested in About Easter Eggs by Georg Franck von Franckenau in 1682 CE. In the European medieval churches, rabbits (hares) were often depicted in Christian art. Beginning in antiquity, rabbits were known for their prolific reproduction, to the point that some writers deemed them hermaphrodites, or the ability to reproduce on their own. This apparently led to the idea of the rabbit as a symbol of virgin birth and thus associated with the Virgin Mary. Again, the rabbit was also a symbol of the fertility goddess Eostre.

In modern culture, the Easter Bunny functions in the same capacity as Santa Claus. The Easter Bunny rewards good children by leaving a full basket on Easter morning. And like Christmas, Easter is an important family affair as a time to get together with members and friends.