The Byzantine Empire existed from 330 to 1453. It is often called the Eastern Roman Empire or simply Byzantium. The Byzantine capital was founded at Constantinople by Constantine I (r. 306-337). The Byzantine Empire varied in size over the centuries, at one time or another, possessing territories located in Italy, Greece, the Balkans, Levant, Asia Minor, and North Africa.

Byzantium was a Christian state with Greek as the official language. The Byzantines developed their own political systems, religious practices, art, and architecture. These were all significantly influenced by the Greco-Roman cultural tradition but were also distinct and not merely a continuation of ancient Rome. The Byzantine Empire was the longest-lasting medieval power, and its influence continues today, especially in the religion, art, architecture, and laws of many Western states, Eastern and Central Europe, and Russia.

The Name 'Byzantine' & Dates

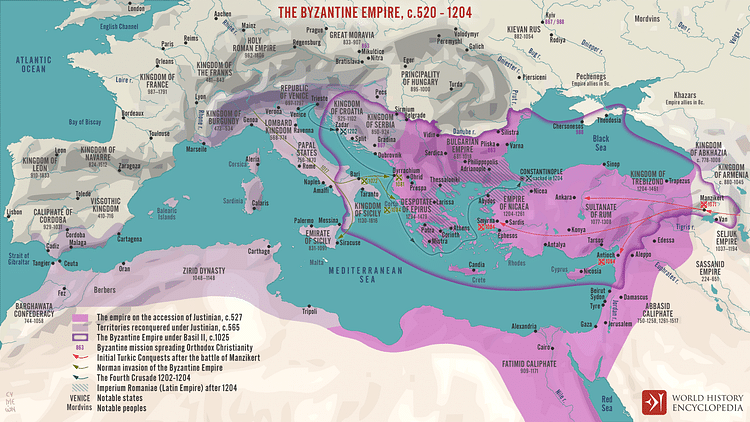

The name 'Byzantine' was coined by 16th-century historians based on the fact that the capital city's first name was Byzantium before it changed to Constantinople (modern Istanbul). It was and continues to be a less-than-perfect but convenient label which differentiates the Eastern Roman Empire from the Western Roman Empire, especially important after the fall of the latter in the 5th century. Indeed, for this reason, there is no universal agreement amongst historians as to what period of time the term 'Byzantine Empire' actually refers to. Some scholars select 330 and the foundation of Constantinople, others the Fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, still others prefer the failure of Justinian I (r. 527-565) to unify the two empires in 565, and some even plum for c. 650 and the Arab conquest of Byzantium's eastern provinces. Most historians do agree that the Byzantine Empire terminated on Tuesday 29 May 1453, when the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II (r.1444-6 & 1451-81) conquered Constantinople.

The discussion of dates also highlights the differences in the ethnic and cultural mix between the two halves of the Roman world and the distinctness of the medieval state from its earlier Roman heritage. The Byzantines called themselves 'Romans', their emperor was basileon ton Rhomaion or 'Emperor of the Romans' and their capital was 'New Rome'. However, the most common language was Greek, and it is fair to say that for the vast majority of its history, the Byzantine Empire was much more Greek than Roman in cultural terms.

Constantinople

The beginnings of the Byzantine Empire lie in the decision of Roman emperor Constantine I to relocate the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Byzantium on 11 May 330. The popular name Constantinople or 'City of Constantine' soon replaced the emperor's own official choice of 'New Rome'. The new capital had an excellent natural harbour on the Golden Horn inlet and, straddled on the border between Europe and Asia, could control the passage of ships through the Bosphorus from the Aegean to the Black Sea, linking lucrative trade between west and east. A great chain stretched across the Golden Horn's entrance, and the construction of the massive Theodosian Walls between 410 and 413 meant that the city was able to withstand time and again concerted attacks from both sea and land. Over the centuries, as more spectacular buildings were added, the cosmopolitan city became one of the finest of any epoch and certainly the richest, most lavish and most important Christian city in the world.

Byzantine Emperors

The Byzantine emperor or basileus (or more rarely basilissa for empress) resided in the magnificent Great Palace of Constantinople and ruled as an absolute monarch over a vast empire. As such, the basileus needed the assistance of an expert government and a widespread and efficient bureaucracy. Although an absolute ruler, an emperor was expected - by his government, people and the Church - to rule wisely and justly. Even more importantly, an emperor had to have military success as the army remained the most powerful institution in Byzantium in real terms. The generals in Constantinople and the provinces could - and did - remove an emperor who failed to defend the empire's borders or who brought economic catastrophe. Still, in the normal run of events, the emperor was commander-in-chief of the army, head of the Church and government, he controlled the state finances and appointed or dismissed nobles at will; few rulers before or since have ever wielded such power.

The emperor's image appeared on Byzantine coins, which were also used to show a chosen successor, often the eldest son, but not always as there were no set rules for succession. Emperors were thought to have been chosen by God to govern, but a magnificent crown and robes of Tyrian purple helped further bolster the right to rule. Another marketing strategy was to copy the reign names of illustrious predecessors, Constantine being a particular favourite. Even usurpers, typically military men of power and success, very often sought to legitimise their position by marrying a member of their predecessors family. Thus, through a carefully orchestrated continuity of dynasties, ritual, costume, and names, the institution of the emperor was able to last for 12 centuries.

Byzantine Government

The Byzantine government followed the patterns established in imperial Rome. The emperor was all-powerful but was still expected to consult such important bodies as the Senate. The Senate in Constantinople, unlike in Rome, was composed of men who had risen through the ranks of the military service, and so there was no senatorial class as such. Without elections, Byzantine senators, ministers, and local councillors largely acquired their position through imperial patronage or because of their status as large landowners.

The elite senators made up the small sacrum consistorium which the emperor was, in theory, supposed to consult on matters of state importance. In addition, the emperor might consult members of his personal entourage at court. Also at court were the eunuch chamberlains (cubicularii) who served the emperor in various personal duties but who could also control access to him. Eunuchs held positions of responsibility themselves, chief amongst these being the holder of the emperor's purse, the sakellarios, whose powers would increase significantly from the 7th century. Other important government officials included the quaestor or chief legal officer; the comes sacrarum largitionum who controlled the state mint; the magister officiorum who looked after the general administration of the palace, the army and its supplies, as well as foreign affairs; and a team of imperial inspectors who kept an eye on affairs in local councils across the empire.

The top official in Byzantium, though, was the Praetorian Prefect of the East to whom all regional governors of the empire were accountable. The regional governors supervised the individual city councils or curae. Local councillors were responsible for all public services and the collection of taxes in their town and its surrounding lands. These councils were organised geographically into 100 or so provinces which were themselves arranged into 12 dioceses, three in each of the empire's four prefectures. From the 7th century the regional governors of the dioceses, or themes as they became known after a restructuring, in effect, became provincial military commanders (strategoi) who were directly responsible to the emperor himself, and the Praetorian Prefect was abolished. After the 8th century the administration of the empire, due to the increased military threat from neighbours and internal civil wars, became much more simplified than previously.

Corpus Juris Civilis

Byzantine government was greatly assisted by the creation of the Justinian Code or Corpus Juris Civilis (Corpus of Civil Law) by Justinian I. The corpus, drawn up by a panel of legal experts, collected, edited, and revised the huge body of Roman laws which had been accumulated over the centuries - a massive number of imperial edicts, legal opinions, and lists of crimes and punishments. The code, composed of over a million words, would last for 900 years, make the laws clearer for all, reduce the number of cases unnecessarily brought before the courts, speed up the judicial process and influence most legal systems in western democracies thereafter.

Byzantine Society

The Byzantines gave great importance to the family name, inherited wealth, and the respectable birth of an individual. The individuals in the higher levels of society possessed these three things. Wealth came from land ownership or the administration of land under an individual administrator's jurisdiction. However, there was no aristocracy of blood as such in Byzantine society, and both patronage and education were a means to climb the social ladder. In addition, the dispensing of favours, lands, and titles by emperors, as well as indiscriminate demotions and the hazards of foreign invasions and wars, all meant that the individual components of the nobility were not static and families rose and fell over the centuries. Rank was visible to all members of society through the use of titles, seals, insignia, particular clothing, and personal jewellery.

Most in the lower classes would have followed the profession of their parents, but inheritance, the accumulation of wealth, and a lack of any formal prohibition for one class to move to another did at least offer a small possibility for a person to better their social position. There were workers with better jobs such as those who worked in legal affairs, administration, and commerce (not a very esteemed way to make a living for the Byzantines). On the next rung down were artisans, then farmers who owned their own small parcels of land, then the largest group - those who worked the land of others, and finally, slaves who were typically prisoners of war but nowhere near as numerous as free labourers.

The role of Byzantine women, as with the men, depended on their social rank. Aristocratic women were expected to manage the home and care for the children. Although able to own property, they could not hold public office and spent their free time weaving, shopping, going to church or reading (although they had no formal education). Widows became the guardian of their children and could inherit equally with their brothers. Many women worked, as men, in agriculture and various manufacturing industries and food services. Women could own their own land and businesses, and some would have improved their social position through marriage. The least respected professions were, as elsewhere, prostitutes and actresses.

Territories of the Byzantine Empire

The geographical extent of the Byzantine Empire changed over the centuries as the military successes and failures of individual emperors fluctuated. Territories which were held in the earlier part of the empire's history included Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine. Greece was less important in practical terms than it was as a symbol of the Byzantine's view of themselves as the true heirs of the Greco-Roman culture. Italy and Sicily had to be defended, ultimately unsuccessfully, against the ambitions of the Popes and the Normans. The Balkans up to the Danube River were important throughout, and Asia Minor up to the Black Sea coast in the north and Armenia in the east was a major source of wealth, but both these regions would require regular and vigorous defence against various perennial enemies.

As the political map was constantly redrawn with the rise and fall of neighbouring empires, notable events included Anastasios I (491-518) successfully defending the empire against both the Persians and Bulgars. Justinian I, aided by his gifted general Belisarius (c. 500-565), won back territories in North Africa, Spain, and Italy which had been lost by the western emperors. The Lombards in Italy and the Slavs in the Balkans made inroads into the Empire during the second half of the 6th century, a situation eventually reversed by Heraclius (r. 610-641), effectively bringing the Persian Sasanian Empire to an end with his victory at Nineveh in 627.

The Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th century robbed the Empire of its territories in the Levant (including Jerusalem in 637), North Africa and eastern Asia Minor. At least, though, the Empire stood firm as a bulwark against the Arab expansion into Europe, with Constantinople twice withstanding determined Arab sieges (674-8 and 717-18). The Byzantine Empire was shaken to its foundations, though. Then in the 9th century, the Bulgars made significant incursions into the northern areas of the Empire. A resurgence in Byzantine fortunes came with the (inappropriately named) Macedonian dynasty (867-1057). The founder of the dynasty, Basil I (r. 867-886), reconquered southern Italy, dealt with the troublesome Cretan pirates, and gained victories against the Arabs on Cyprus, mainland Greece and in Dalmatia. The very next emperor, Leo VI (r. 886-912) lost most of the gains, but the mid-10th century saw victories in Muslim-controlled Mesopotamia.

Basil II (r. 976-1025), known as the 'Bulgar-Slayer' for his victories in the Balkans, oversaw another startling upturn in Byzantine fortunes. Basil, helped by an army of fierce warriors of Viking descent from Kiev, also won victories in Greece, Armenia, Georgia, and Syria, doubling the size of the Empire. It was though, the last great hurrah as a gradual decline set in. After the shocking defeat to the Seljuks at the Battle of Manzikert in Armenia in 1071, a brief revival occurred under Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118) with victories against the Normans in Dalmatia, the Pechenegs in Thrace, and the Seljuks in Palestine and Syria (with the help of the First Crusaders), but there seemed to be too many enemies in too many regions for the Byzantines to prosper indefinitely.

In the 12th and 13th century the Sultanate of Rum took half of Asia Minor, and then disaster struck when the armies of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204. Carved up between Venice and its allies, the Empire existed only in exile before a restoration in 1261. By the 14th century the Empire consisted of a small area in the tip of southern Greece and a chunk of territory around the capital. The final blow came, as already mentioned, with the Ottoman sack of Constantinople in 1453.

The Byzantine Church

Paganism continued to be practised for centuries after the foundation of Byzantium, but it was Christianity which became the defining feature of Byzantine culture, profoundly affecting its politics, foreign relations, and art and architecture. The Church was headed by the Patriarch or bishop of Constantinople, who was appointed or removed by the emperor. Local bishops, who presided over larger towns and their surrounding territories and who represented both the church and emperor, had considerable wealth and powers in their local communities. Christianity, then, became an important common denominator which helped bind together diverse cultures into a single empire which included Christian Greeks, Armenians, Slavs, Georgians, and many other minorities, and those of other faiths such as Jews and Muslims who were permitted to freely practise their religion.

The differences in the eastern and western church was one of the reasons that the Byzantine Empire received such a poor representation in western medieval histories. Frequently Byzantines were portrayed as decadent and shifty, their culture stagnant, and their religion a dangerous heresy. The churches of the east and west disagreed on who should have priority, the Pope or the Patriarch of Constantinople. Matters of doctrine were also contested, such as did Jesus Christ have one human and one divine nature combined or just a divine nature. Clerical celibacy, the use of leavened or unleavened bread, the language of service, and the use of imagery were all points of differences, which, with the fuel of political and territorial ambitions added into the volatile mix of emotions, led to the Church Schism of 1054.

The Byzantine church also had its own internal disputes, most infamously the iconoclasm or 'destruction of images' of 726-787 and 814-843. The Popes and many Byzantines supported the use of icons - representations of holy figures but especially Jesus Christ. Those against icons believed they had become idols and it was blasphemous to think that God could be represented in art. The issue also reignited the debate over whether Christ had two natures or one and whether an icon, therefore, only represented the human. Defenders of icons said that they were merely an artist's impression and helped the illiterate better understand the divine. During the wave of iconoclasm, many precious artworks were destroyed, especially during the reigns of Leo III (r. 717-741) and his successor Constantine V (r. 741-775) when even people who venerated icons (iconophiles) were persecuted. The issue was resolved in favour of icons in 843, an event known as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy".

Monasticism was a particular feature of Byzantine religious life. Men and women retired to monasteries where they devoted their lives to Christ and helping the poor and sick. There they lived a simple life according to rules laid out by such important church figures as Basil the Great (c. 330 - c. 379). Many monks were also scholars, most famously Saint Cyril (d. 867) who invented the Glagolitic alphabet. A notable woman who used her time of retreat well was Anna Komnene (1083-1153), who wrote her Alexiad on the life and reign of her father Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118). Monasteries thus became invaluable repositories of texts and knowledge while their wine-production and icon workshops were greatly appreciated, too. One of the most celebrated monastic sites is Mount Athos near Thessalonica, where monks established themselves from the 9th century, eventually building 46 monasteries there, many of which survive today.

Byzantine Art

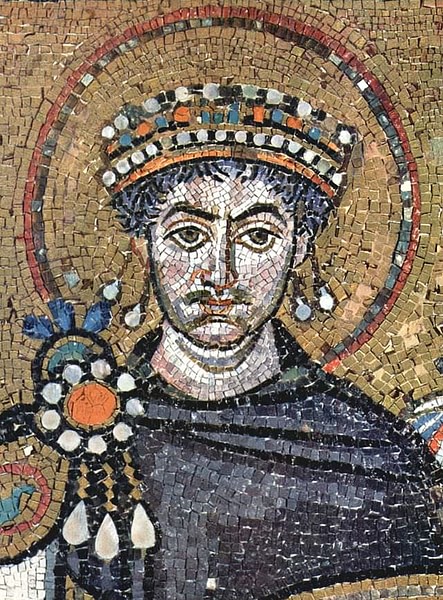

Byzantine artists moved away from the naturalism of the Classical tradition towards the more abstract and universal, displaying a definite preference for two-dimensional representations. The rarity of signatures on works of art produced before the 13th century suggests that artists did not enjoy a high social status. Artworks which promoted a religious message - principally the need for salvation and a reinforcement of faith - were produced in huge numbers and chief amongst these were wall mosaics, wall paintings, and icons. Although icons could take almost any form of material, the most popular were small painted wooden panels. Designed to be carried or hung on walls, they were made using the encaustic technique where coloured pigments were mixed with wax and burned into the wood as an inlay. With the purpose of facilitating communication between the onlooker and the divine, the single figures are typically full frontal with a nimbus or halo around them to emphasise their holiness.

Byzantine mosaics, best seen today in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul or the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, represented holy figures, emperors and empresses, church officials, and scenes of daily life, especially in agriculture. Large-scale sculpture seems to have been less popular than in earlier antiquity, but sculpted marble sarcophagi were produced in great numbers. Finally, metalwork, especially incorporating enamel-work and cabochon semi-precious stones, was a Byzantine speciality, and artisans produced many high-quality and intricately designed plates, cups, jewellery of all kinds, book covers (especially for Bibles), and reliquaries (boxes for keeping holy relics).

Byzantine Architecture

Byzantine architects continued to employ the Classical orders in their buildings and took ideas from the Near East, amongst other places. Designs became more eclectic than in antiquity, especially given the common habit of reusing the materials from older buildings for new structures. There was, too, a definite emphasis on function over form and a greater concern with the interiors rather than exteriors of buildings. Continuing to build such quintessentially Roman structures as arched aqueducts, amphitheatres, hippodromes, baths and villas, the Byzantines would add to the repertoire with their domed churches, walled monasteries, and more sophisticated fortification walls.

Favoured building materials were large bricks with mortar and concrete for the hidden core of walls. Ashlar stone blocks were used in more prestigious public buildings while marble, used more sparingly than in earlier Roman times, was generally reserved for columns, door and window frames, and other decorative elements. Roofs were of timber while interior walls were frequently covered in plaster, stucco, thin marble plaques, paintings, and mosaics.

The largest, most important and still most famous Byzantine building is the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople, dedicated to the holy wisdom (hagia sophia) of God. Built anew in 532-537, its basic rectangular shape measures 74.6 x 69.7 metres (245 x 229 ft) and its huge domed ceiling is 55 metres above the floor, spanning 31.8 metres in diameter. Resting on four massive arches with four supporting pendentives, the dome was a spectacular architectural achievement for the period. The Hagia Sophia remained the biggest church in the world until the 16th century and was one of the most decorated with superb glittering mosaics and wall paintings.

Christian churches, in general, were one of the Byzantine's greatest contributions to architecture, especially the use of the dome. The cross-in-square plan became the most common with the dome built over four supporting arches. The square base of the building then branched into bays which might themselves have a half or full dome ceiling. Another common feature is a central apse with two side-apses at the eastern end of the church. Over time, the central dome was raised ever higher on a polygonal drum, which in some churches is so high it has the appearance of a tower. Many churches, especially basilicas, had alongside them a baptistry (usually octagonal), and sometimes a mausoleum for the founder of the church and their descendants. Such Byzantine design features would go on to influence Orthodox Christian architecture and so are still seen today in churches worldwide.