The Ecclesiazusae (aka Assemblywomen) is a comedy play written by Aristophanes, one of the great Greek comic playwrights. Written sometime between 393 and 391 BCE, it is, along with his play Wealth, one of only two he wrote after the Athenian defeat in the Peloponnesian War. In 403 BCE a new democratic government was reestablished in Athens; however, continued conflicts with Sparta had drawn heavily on both the finances of the city and its manpower. The future of the city remained in question. In the Ecclesiazusae Aristophanes proposed a unique solution: turn the running of the government over to the women of the city. As in his play Lysistrata, the central character of the play is a strong-willed woman - Praxagora. Together with other wives, who are disguised as men, she presents her ideas at the Assembly of Athens and convinces the men to relinquish control of the government. As the newly appointed commander, Praxagora quickly enacts a series of radical changes: community property, communal dwellings and meals, and no brothels. Reluctantly, many of the men quickly adapt to the new order of things. Of course, the possibility that women might rule in a city where they could not normally even vote and Aristophanes' use of that notion for comedy is indicative of just how male-dominated the society of ancient Athens was.

Life of Aristophanes

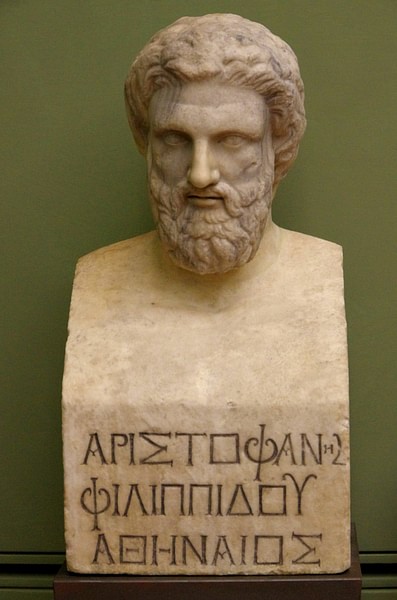

Aristophanes was one of the best examples of the “grace, charm, and scope” of Old Attic Comedy. Unfortunately, his works from this period are the only ones known to exist - only eleven of his plays have survived. Very little is known of his early life. Since most of his plays were written between 427 and 386 BCE, it helps place his death around 386 BCE. A native of Athens, he was the son of Philippus and owned land on the island of Aegina. He had two sons, one of whom became a playwright of minor comedies. Although participating little in Athenian politics, Aristophanes was an outspoken critic, via his plays, of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and those politicians who supported it. His portrayal and attack of the statesman Cleon in the play The Babylonians landed him in court in 426 BCE. Author Edith Hamilton, in her book The Greek Way, said that Aristophanes wore the “halo of Greece” and that all of life could be seen in the plays of Aristophanes; politics, war, pacifism, and religion.

By the time Aristophanes began to write, Greek drama was in serious decline. Although Aristophanes is sometimes condemned for bringing drama down from the high-level of the tragedian Aeschylus, his plays, with their simplicity and vulgarity, have been recognized and appreciated for their rich fantasy as well as humor and indecency. Editor Moses Hadas in his book Greek Drama wrote that while Aristophanes could write poetry that was delicate and refined, he could also, at the same time, demonstrate bawdiness and gaiety. To many his comedies were a blend of wit and invention. Although somewhat quiet on the subject of Athenian politics, Aristophanes opposed all changes in the traditional aspects of philosophy, education, poetry, and music. Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity said the playwright reflected the conservative opinion of many Athenians, showing them to be people who valued old simplicity and morality. In short, they viewed all new innovations as being subversive.

Cast of Characters

The rather lengthy cast of characters includes: Praxagora, First woman, Second woman, Chorus leader, Chorus of Athenian women, Maid to Praxagora, Girl crier, Blepyrus, Chremes, Neighbor, Citizen, Girl, Young man, First hag, Second hag, Third hag, and lastly the silent Sicon, Parmenon, Dancing girls, and a crowd of citizens and neighbors.

Play Summary

Outside her home in Athens, Praxagora waits anxiously for her female friends to arrive. She carries her husband's cloak and walking stick along with a fake beard. It is an opening scene similar to Aristophanes' Lysistrata. Shortly, the other women arrive - all carrying the same items. It is early morning and Praxagora chastises the women for being late: they have to be at the Assembly in order to be seated near the front. Praxagora quickly rehearses the speech she plans to make. The women, dressed as men, arrive at the Assembly and seat themselves as planned. Although some of the men remark how these strangers are somewhat pale, the women go largely unnoticed.

The scene switches to Praxagora's house where her husband Blepyrus exits his home wearing his wife's robe and slippers. He wonders where his wife is and what has happened to his cloak and walking stick. His friend and neighbor Chremes appears and tells him of the happenings at the Assembly. The major topic of the day was what could be done to save the city. Although unrecognized by Chremes, Praxagora (dressed as a man) had addressed the men and convinced them to hand the reins of government over to the women. Since it was the only thing that had not been tried - and since the women were (in the words of Praxagora) harder workers – the men had little choice but to agree. Serving as the city's new commander, Praxagora suggested several radical ideas: equal pay for men and women, no more lawsuits, common living areas, and the courthouse and porticos would become common dining halls. Since individual ownership would be non-existent, there would be no private wealth. Instead, there would be a common stock of necessities for everybody. Slavery still existed but there was common ownership; the slaves still performed all the necessary work.

Although there was some resistance, the men soon adapted to the new laws and even brothels were outlawed. Although some rules were enacted, men and women could sleep with whomever they wished: In the closing scene of the play three elderly hags argue over a much younger man.

The Play

The play begins in the early morning hours on a quiet street in Athens. Praxagora exits her home carrying her husband's cloak, shoes, walking stick, and a fake beard. She is obviously troubled. The Assembly will be meeting soon, but her friends have yet to arrive. “It'll be time for the Assembly and those of us who are in on the plot…have yet to get to our seats and settle our limbs without being spotted” (223). Soon, several other ladies arrive. They all have excuses for their tardiness. “I was just putting my shoes on when I heard you scratching at the door. I haven't slept a wink” (224).

Praxagora's major concern is that they all get seats near the platform facing the praesidium.

If we get to our seats first we can settle down and no one will notice us; we'll have our cloaks well-wrapped round us, and when we are sitting there, with our beards tied on, there'll be nothing to show we're not men. (225)

They began to practice their individual speeches, but they are all hopeless. Praxagora realizes that she will have to do all the speaking. She practices her speech:

Gentlemen, my interest in the welfare of this state is no less than yours; but I deeply deplore the way in which its affairs are being handled. The task of speaking for the people is invariably entrusted to crooks and rascals. For every one day they spend doing good they spend another ten doing irreparable harm...the state is left to stagger on as best it can, like Aesimus on his way home from a party. But if you will only listen to me, the situation is saved. I propose that we hand over the running of Athens to the women. (228-9)

The women are elated and suggest that if the proposal is accepted Praxagora will be named the “Generalissimo.” Together they head for the Assembly.

The scene changes to Praxagora's husband Blepyrus standing outside their home. He is wearing his wife's slippers and gown. He tells a neighbor that he cannot find his cloak and shoes anywhere. And, he also cannot find his wife: “I'd very much like to know what mischief she's up to” (234). A friend, Chremes, arrives and immediately makes a comment on the poor husband's gown and slippers.

Changing the subject, he has been to the Assembly that day, and though he arrived too late and would not get paid, he stayed, for it was the day to hear proposals on how to save the city. He told how several men had stood up and given their ideas. Then a good-looking young man rose and gave a speech, saying that they should hand over control of affairs to the women: “… women, he says are creatures bursting with intelligence and darned good at making money, And they don't let out what happens at their secret festivals, the way you and I, when we're on the Council, leak state secrets right and left” (237). Blepyrus agreed and asked about the final vote. The Assembly decided it was going to hand over control of the city to the women. The general feeling was that it was the only thing that hadn't been tried -“They might as well try it”(237). Blepyrus, unaware that it was his wife who had made the proposal, questioned the decision: the women will have all the jobs that men usually do? The women will have to sit on the juries? He can stay at home and relax? Chremes commented that if it benefits Athens then it is every man's patriotic duty. Praxagora arrives home to her unsuspecting husband. He wonders if she has a lover and asks why she took his cloak and walking stick.

More than with her being gone, he was mad because he could not go to the Assembly. She plays ignorant - did the Assembly meet? He tells her of the decision at the Assembly - they are going to hand over everything to the women. She replies “by Aphrodite” that it is a great day for Athens, a splendid piece of news: “This'll put a stop to all the mischief and skullduggery! No more faked evidence, no more informing!” (241). They will be no more mugging in the streets, no envy of a neighbor, no more poverty and no more slander. Chremes adds that if it all comes true then it sounds good to him. To Chremes and the chorus she speaks of her proposals: there will be one stock of essentials for everybody - everybody sharing equally; all money and private possessions will become common property. Everything will be owned in common. Marriages will be ended - one can sleep with whomever he or she wishes. The brothels will be closed. And, lastly, there won't be any court cases for no one will be stealing: “Everyone will have the necessities of life” (245). The law courts and arcades will be converted into dining halls.” The city will become “one communal residence.”

The scene changes to Chremes' home where he is removing various items to hand over to the state, according to the new law. A citizen questions Chremes' compliance and adds that he refuses to comply. “I shall take jolly good care not to hand it in until I see that other people decide to do” (248). To him, it was not the Athenian way - “grabbing not giving.” A crier appears and tells them that they are to present themselves before “Her Excellency the General” to draw lots to see where they will dine that day. The citizen, who refused to give up his property, still plans to dine at the communal table, “and I must find some way of keeping what I've got without losing my share of all this public feasting” (252).

Elsewhere in the city, two old hags are wondering when the men will arrive. A beautiful young girl argues with the first old hag; they disappear into their home. A young man appears - he wonders how he can sleep with the young girl without sleeping with one of the old hags. However, he is told, according to the law that he must sleep with one of them. As they continue to argue a third hag appears, and they drag the poor young man into their house. Across town the public feast is almost over - Praxagora is happy. Her husband is cheerfully on his way to the banquet accompanied by a number of young dancing girls.

Conclusion

The long war with Sparta was finally over and Athens was attempting to recover. For Aristophanes his personal struggle with the war and the politicians who favored it should have brought him some long deserved peace. However, a new question emerged: how could the city be saved? The Ecclesiazusae was one of the playwright's last comedies, and in it, he attempts to present a unique solution to Athens' problem: turn the control of the government over to the women. It was the one alternative that had not been tried but, of course, the play is a comedy and it is important to note that the very idea of women ruling was fantastic to the male-dominated world of the ancient Greeks. Nevertheless, some of Praxagora's proposals - communal dwellings and meals - are similar to those found in Plato's The Republic. However, many scholars dismiss this as mere coincidence because Plato's work had not been in wide circulation at the time of the play's writing. By the play's end the city seemed to have accepted the radical changes. The final scene has Praxagora's husband headed to the banquet accompanied by a bevy of dancing girls.