Edda is a term used to describe two Icelandic manuscripts that were copied down and compiled in the 13th century CE. Together they are the main sources of Norse mythology and skaldic poetry that relate the religion, cosmogony, and history of Scandinavians and Proto-Germanic tribes. The Prose or Younger Edda dates to circa 1220 CE and was compiled by Snorri Sturluson, an Icelandic poet and historian. The Poetic or Elder Edda was written down circa 1270 CE by an unknown author.

Etymology of 'Edda'

Snorri Sturluson's work was the first of the two manuscripts to be called Edda, however, scholars are uncertain how this exactly came about. Snorri himself did not name it. The term, 'Edda', was later ascribed to Snorri's work by a different author in a manuscript from the early 14th century CE, the Codex Upsaliensis, which contained a copy of Snorri's Edda within it. Gudbrand Vigfusson, in The Poetry of the Old Northern Tongue, quotes the Codex Upsaliensis as saying, “This Book is called Edda, which Snorri Sturlason put together according to the order set down here: First, concerning the Æsir and Gylfi.” The first use of the word 'Edda', that has thus far been located, was in a poem called the Lay of Righ (Háttatal), which was authored by Snorri. In this poem, the word 'Edda' is used as a title for “great-grandmother.” Multiple theories exist, but one suggests that the term may have become associated with Snorri's manuscript because, like a great-grandmother, it carries a breadth of ancient knowledge and wisdom. Another theory that is more widely accepted by scholars today proposes that 'Edda' is closely associated with the word Oddi, which is the Icelandic town where Snorri grew up.

The Prose Edda

Snorri Sturluson's Edda was later called the Prose Edda, due to his addition of prose explanations of the difficult alliterative verse and symbolism. It appears that Snorri designed the manuscript as a textbook on skaldic poetry. However, it has been most highly prized for the songs and poems that record an incredible array of mythology, heroes, and battles. His verse was reflective of older styles of court poetry and was esteemed as a high standard for other poets. It was a standard perhaps unattainable by future generations of poets, as it was considered by many as overly cryptic and difficult.

Snorri's Edda was later nicknamed the 'Younger Edda' because much of it derives from older sources. What those sources were is a matter of speculation. Some researchers believe Snorri based it largely on folkloric oral traditions that he may have heard, while others think he used an elder written Edda. However, experts agree that he did add many of his own details. As a result, he gives readers a more elaborate version of Norse mythology that at times reveals his Christian influence.

Contents of the Prose Edda

- Prologue: Snorri reveals his Christian influence by giving an account of the Biblical version of creation with the stories of Adam and Eve, the Great Flood and Noah's Ark.

- Gylfaginning: Here Begins the Beguiling of Gylfi - Perhaps truest to ancient sources, this book is a mythological story in the form of Odinic poems that explain the origin of the Norse cosmos and the chaos that will ensue.

- Skáldskaparmál: The Poesy of Skalds - This text continues with mythological stories of the Norse gods but weaves educational explanations on skaldic poetry into the narrative.

- Háttatal: The Enumeration of Metres - Includes three distinct songs that celebrate King Hákon and Skúli Bárdsson, the powerful father-in-law of the king. Snorri added comments and definitions between stanzas to ease the reader's difficulty of interpretation.

Poetry From the Prose Edda

The following excerpt from the first book in the Prose Edda, 'Gylfaginning', connects the Poetic and Prose Edda together. In it, Snorri references the 3rd stanza of Völuspá, the most famous poem of the Poetic Edda that details the mythological creation and destruction of the Norse cosmos. This story in the Prose Edda is about King Gylfi of Scandinavia who travels to investigate the wise and cunning leaders of the east. The king pretends to be an old man, Gangleri, who asks many questions of the leaders.

Gangleri said: 'What was the beginning, or how began it, or what was before it?' Hárr answered: 'As is told in Völuspá

Erst was the age | when nothing was:

Nor sand nor sea, | nor chilling stream-waves;

Earth was not found, | nor Ether-Heaven,—

A Yawning Gap, | but grass was none.

(Gylfaginning: Chapter IV)

An Elder Edda Surfaces

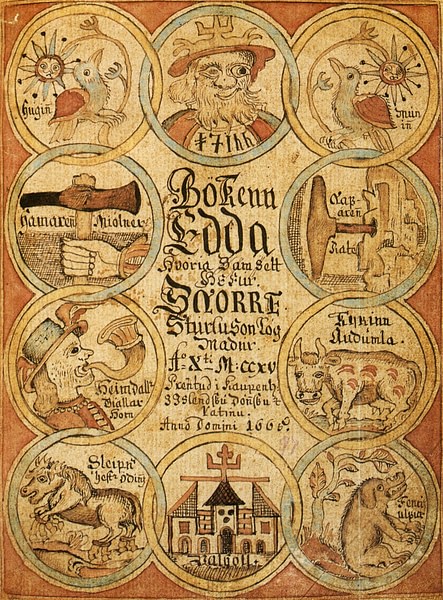

In 1643 CE, a highly respected Icelandic collector of numerous works on Norse literature, Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson, obtained a copy of an older manuscript. No scholar knows where it came from or if it originally had a name, however, it was evident that the newly discovered compendium and Snorri's Edda had some common origins. Although the bishop attributed this manuscript to the priest and author, Saemundur Sigfússon (1056-1153 CE), and called it Saemundur's Edda, today, scholars agree that this was incorrect. The author/compiler is still unknown. However, Bishop Brynjólfur believed the manuscript to be the Elder Edda. Completely written in verse, the Elder Edda later became known as the Poetic Edda to distinguish it from Snorri's prose counterpart.

In 1662 CE, Bishop Brynjólfur gifted many of his important literary collections to the King of Denmark, Frederick III, to place in the new Royal Library. The Poetic Edda was among those gifts. It became known as the Codex Regius ('King's or Royal Book') and remained safeguarded in Denmark until it was returned to Iceland in 1971 CE.

The Codex Regius is a cherished artefact containing ancient myths and stories of heroes that cannot be found elsewhere. Older copies of the Codex Regius and its sources that may have once existed were lost or destroyed. It currently contains 90 pages, but 16 of those went missing sometime after it went to Denmark. The Poetic Edda took a bit of an evolutionary divergence from the Codex Regius as other poems were added to the Poetic Edda over the years. Today, many people refer to the oldest King's Book as the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda to distinguish it from a different volume of Codex Regius, which contains a copy of Snorri's Edda and dates to the first half of the 14th century CE. The contents of any modern Poetic Edda vary and depend on the author.

Contents of the Poetic Edda (Codex Regius)

Mythological Poems:

- Völuspá - The Seeress's Prophecy

- Hávamál - Sayings of the High One

- Vafþrúðnismál - The Ballad of Vafthrúdnir

- Grímnismál - The Lay of Grímnir

- Skírnismál - The Lay of Skírnir

- Hárbarðsljóð - The Lay of Hárbard

- Hymiskviða - The Lay of Hymir

- Lokasenna - Loki's Wrangling

- Þrymskviða - The Lay of Thrym

- Völundarkviða - The Lay of Völund

- Alvíssmál - The Lay of Alvís

Heroic Poems:

Three lays of Helgi

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana I or Völsungakviða

- Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana II or Völsungakviða in forna

- Frá dauða Sinfjötla - A short prose text

- Grípisspá - Grípir's Prophecy, The Prophecy of Grípir

- Reginsmál - The Lay of Regin

- Fáfnismál - The Lay of Fáfnir

- Sigrdrífumál - The Lay of Sigrdrífa

- Brot af Sigurðarkviðu - Fragment of a Sigurd Lay

- Guðrúnarkviða I - The First Lay of Gudrún

- Sigurðarkviða hin skamma - The Short Lay of Sigurd

- Helreið Brynhildar - Brynhild's Ride to Hel

- Dráp Niflunga - The Slaying of The Niflungs

- Guðrúnarkviða II - The Second Lay of Gudrún

- Guðrúnarkviða III - The Third Lay of Gudrún

- Oddrúnargrátr - Oddrún's Lament

- Atlakviða - The Lay of Atli

- Atlamál hin groenlenzku - The Greenlandic Poem of Atli

- The Jörmunrekkr Lays

- Guðrúnarhvöt - Gudrún's Lament

- Hamðismál - The Lay of Hamdir

Poems Added That Are Not in the Codex Regius

- Baldrs draumar - Baldr's Dreams

- Gróttasöngr - The Song of Grotti

- Rígsþula - The Lay of Ríg

- Hyndluljóð - The Lay of Hyndla

- Völuspá - Short Prophecy of the Seeress

- Svipdagsmál - The Lay of Svipdag

- Grógaldr - Gróa's Spell

- Fjölsvinnsmál - The Lay of Fjölsvid

- Hrafnagaldr Óðins - Odins's Raven Song

Poetry from the Poetic Edda

One of the most important mythological poems is Hávamál, in which Odin explains how he acquired the runes by sacrificing himself to himself on the Yggdrasil tree. As translated by Olive Bray, stanzas 137 and 138 explain:

I trow I hung on that windy Tree

nine whole days and nights,

stabbed with a spear, offered to Odin,

myself to mine own self given,

high on that Tree of which none hath heard

from what roots it rises to heaven.

None refreshed me ever with food or drink,

I peered right down in the deep;

crying aloud I lifted the Runes

then back I fell from thence.

Preservation of Germanic History

It was by good fortune that the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda was preserved. Widespread destruction of pagan manuscripts occurred in the 18th century CE across Europe. Additionally, in 1728 CE the Great Fire in Copenhagen tragically burned at least one-third of the city including over 35,000 volumes of books and a large collection of historical documents at the University of Copenhagen library.

Today, the Eddas are a key to the ancient world of Germanic history. More than just a vast source of mythology, the Eddas reveal the intimate relationships between humans, gods, and nature, and the deep reverence that was built upon these beliefs. This is especially significant in light of a resurgence of Icelandic Pagan religion. Additionally, the extensive usage of the Eddas across the world as resources for Norse studies testifies to their scholastic relevance. Both the Prose and Elder Eddas are national treasures that have captured history within their poetic pages and are a testament to the tenacity of the Icelanders to remember and preserve their precious heritage.