Edward England was an Irish pirate who operated in the Caribbean, the Eastern Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean between 1717 and 1720 during the Golden Age of Piracy (1690-1730). Captain England’s successful but brief pirate career came to an end when he was marooned by his crew on the island of Mauritius in 1720.

Early Career

Captain England has his own chapter in the celebrated pirate’s who’s who, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, compiled in the 1720s. The book was credited to a Captain Charles Johnson on its title page, but this is perhaps a pseudonym of Daniel Defoe (although scholars are still debating the issue, and Charles Johnson may have been a real, if entirely unknown pirate expert). As with many other pirates, the General History is an invaluable source on England’s career, even if there are fictional additions to the factual information laboriously garnered from such sources as court records, official documents, and letters of the period.

Edward England’s real name was possibly Jasper Seager (or Seegar). Like many pirates of the period, England was obliged to join a pirate crew after the ship on which he was serving was captured. England had been an officer on a Jamaican sloop when it was taken by Christopher Winter, who was based at the pirate haven of New Providence in the Bahamas. The General History gives the following not unfavourable assessment of England’s character:

England was one of those men, who seemed to have such a share of reason, as should have taught him better things. He had a great deal of good nature, and did not want for courage; he was not avaricious, and always averse to the ill usage prisoners received: he would have been contented with moderate plunder, and less mischievous pranks could his companions have been brought to the same temper, but he was generally over-ruled. (114)

Following the successful attacks on pirates in their haven at New Providence (now Nassau) by Woodes Rogers, Governor of the Bahamas from 1717, England sailed across the Atlantic to continue his piracy elsewhere. Several merchant ships were captured in the Azores, Cape Verde Islands, and off the coast of West Africa.

In 1718, England himself obliged an otherwise honest man to turn pirate when he captured the Welshman Howell Davis who had been chief mate on a slave ship, the Cadogan of Bristol. The captain of the Cadogan was murdered, and Davis was given command of the slaver despite refusing to formally sign England’s ship’s articles and become a part of his pirate crew. Impressed with Davis’ courage, England allowed him to sail off. Davis ended up in Barbados where he was captured. Davis managed to escape prison, and he continued a pirate career on both sides of the Atlantic, a spree that ended with his death on Principe Island in 1719.

England was, for a time, an associate of the most successful of all pirates in the so-called Golden Age, Bartholomew Roberts (aka 'Black Bart' Roberts, c. 1682-1722). In the relatively small world of pirates, Roberts had taken over the crew of Howell Davis after the latter’s death. Roberts and England operated off the coast of Guinea, West Africa. England operated two ships: his own sloop and another prize renamed Victory. Command of the latter was given to John Taylor and together they raided the western coast of India and took more prize ships. When required, provisions were taken on board at the pirate base on Madagascar.

Piracy on the High Seas

Edward England was known to have flown the now-classic version of the Jolly Roger pirate flag with a white human skull above crossbones on a black background. Hoisted prior to an attack to encourage immediate surrender, England often flew other flags simultaneously such as the red flag (to indicate no quarter would be given) and the Union Jack.

In early 1719, England had captured the sloop Pearl and refitted it to make it faster and more manoeuvrable so that he could abandon his own sloop in the typical pirate process of steadily increasing ship size, capture after capture. The ship’s superstructures were pulled down, and it was renamed the Royal James. In 1719, the Royal James was used to good effect, capturing at least 12 prizes off the coast of West Africa, including the 12-gun Bentworth of Bristol. All of these prizes are catalogued by Johnson/Defoe with their names, crew strength, and firepower.

In 1720, England upsized again after capturing a ship off Madagascar and so he abandoned the Royal James. This new ship he renamed the Fancy, and it boasted 34 cannons, impressive for a pirate ship, although less than the least-armed naval vessels of the period. England’s crew of around 180 men was reported as being made up of Europeans, indigenous Americans, and black Africans, the latter being slaves captured on vessels or slaves who had escaped from their terribly harsh life on a colonial plantation.

England’s crew took their greatest prize in the Mascarene Islands near Madagascar. The victim was a Portuguese ship that, with 60-70 cannons, would have been too powerful for the pirates to consider a target if it had not been undergoing repairs after being badly bashed around in a recent storm. The ship was carrying a large amount of high-value goods and, something even more valuable than those, the viceroy of Portuguese Goa. According to the General History, by far the most sparkling part of the cargo was $3-$4 million dollars worth of diamonds, enough for 42 diamonds for each member of England’s crew.

The Battle with the Cassandra

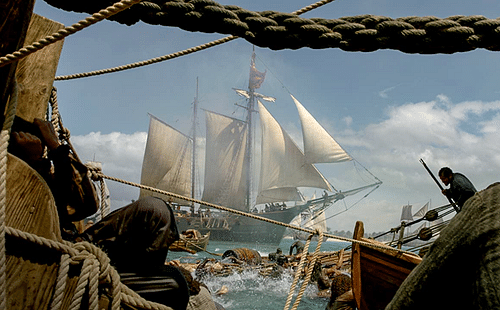

In July-August 1720, the Fancy and the Victory (still commanded by Taylor) were severely tested in an encounter near Johanna Island (now Anjouan in the Comoros group) in the Indian Ocean with a British East India Company ship, the Cassandra. The latter had been in the company of two other merchant ships, but these abandoned Cassandra’s captain James McRae to face both the Fancy and the Victory with a combined firepower of 64 cannons. McRae gives the following account of the battle which ensued in a letter dated 16 November 1720:

[We were left] engaged with barbarous and inhuman enemies with their black and bloody flags hanging over us, without the least appearance of escaping being cut to pieces. But God, in his good Providence determined otherwise, for notwithstanding their superiority, we engaged them both about three hours, during which, the biggest received some shot betwixt wind and water, which made them keep off a little to stop their leaks.

The other endeavoured all she could to board us, by rowing with her oars, being with half a ship’s length of us above an hour but by good fortune we shot all her oars to pieces, which prevented them, and by consequence, saved our lives.

About 4 o’clock, most of the officers and men posted on the quarterdeck being killed and wounded…we endeavoured to run ashore…we had considerable advantage by having a broadside to his bow, we did him great damage…[but] many of my men were killed or wounded and no hopes left of us from being all murdered by enraged barbarous conquerors, I ordered all that could, to get into the longboat under the cover of the smoke of our guns, so that with what some did in boats, and others by swimming, most of us that were able reached ashore by 7 o’clock. When the pirates came aboard, they cut three of our wounded men to pieces. I, with a few of my people made what haste I could to the King's town, 25 miles from us, where I arrived next day, almost dead with fatigue and loss of blood, having been sorely wounded in the head by a musket ball.

(quoted in Konstam, The Pirate Ship, 35-7)

Captain England had won the prize, albeit at the high cost of considerable damage to his two ships and the loss of over 90 men. The cargo of the Cassandra was looted and valued at around £75,000 (over £15 million or $20 million today) plus the added bonus of a medicine chest.

Marooning

While some pirate captains were deposed for being too harsh on captives and their own crew, Edward England was considered a little too soft on prisoners by his men and so was voted out of office. After it was thought England had allowed McRae to escape, the pirate captain’s men decided this was the last straw, and they voted to maroon him on Mauritius along with three other men. England, as was usual with marooning, was given only a keg of water and a pistol and some powder so that he might shoot himself when things got really tough. However, Mauritius was (and is) no desert island, and the enterprising England managed to find food and acquire or build a small boat or raft and make it to the pirate haven on Madagascar. The ultimate fate of England is not known for certain, but he most likely died in poverty and obscurity, a fate of many pirates from 1720 onwards as the Royal Navy significantly increased its presence in the region and the seas were made safer for merchant vessels.