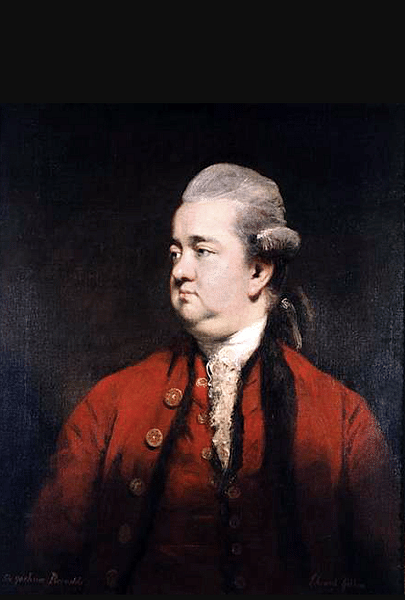

Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) was an English historian most famous for his influential work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, volume one of which was published in 1776, with the final sixth volume coming in 1788. Gibbon's history was a bestseller, and in it, he attributes the decline of Rome to its increasing Christianization and departure from traditional civic values. Most historians today question Gibbon's omissions, inaccuracies, and bias, but the work remains important in Roman studies. In addition, Gibbon created a lasting trend to view history in the light of how it affects the present day.

Early Life

Edward Gibbon was born on 27 April 1737 in Putney in the English county of Surrey. His father belonged to the landed gentry, but his relationship with his son, the only survivor of his seven children, was difficult. Edward's mother died when he was only nine years old. A sickly child, Edward was often too ill for school, but he became an avid reader, educating himself and establishing a scholarly independence that would stay with him throughout his life. Brought up a Protestant, Edward converted to Catholicism when he was studying at Magdalen College in Oxford. His father, dismayed at this turn of events, sent his son to Switzerland to be educated in Lausanne, where he resided with the Calvinist Reverend Daniel Pavillard. The strategy worked as Edward converted back to Protestantism; he also learnt much about French literature.

It was in Switzerland that Edward met and fell in love with the daughter of a pastor, Suzanne Curchod (1739-1794). Edward's father did not approve of the match, and so nothing came of it except regrets. Curchod went on to marry Jacques Necker (1732-1804), the famous Swiss banker and finance minister of Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792).

By 1758, Gibbon was back in England, where he worked on his first published piece, Essai sur l'étude de la littérature (Essay on the Study of Literature). Not published until 1761, the essay argued the great usefulness of studying antiquity and classical authors. The work showed the writing style that Gibbon had acquired during his time on the Continent. He once explained why he wrote in French: "because I think in French and, strange as it may seem, I can say, with some shame but no affectation, that it would be a matter of difficulty to me to compose in my native language" (Hampson, 56).

In 1759, he found himself serving as a captain in the Hampshire militia in defence of England during the Seven Years' War, a position he held until the end of that Europe-wide conflict in 1763. He then visited France and met such noted philosophers as Denis Diderot (1713-1784).

Roman History

Gibbon visited Rome in 1764 as part of his three-year grand tour that took in the sights in Italy, France, and Switzerland. According to his own account, he was inspired to write a history of Rome after he witnessed a group of friars giving their evening prayers inside the ruined Temple of Jupiter. As it turned out, Gibbon first tackled a more manageable history of Switzerland, but he abandoned this project before completion. He then moved in the opposite direction and went for something much more specific, his Critical observations on the sixth book of the Aeneid, published in 1770. But it was the Roman Empire that still appealed to his imagination as a historian, and so he began his magnum opus.

In his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Gibbon set out to examine the history of the Roman Empire, starting in the early 2nd century CE and, despite its title, going way beyond the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century CE. Gibbon gives the reader a vast panorama of the Roman world, including what became known as the Byzantine Empire (aka the Eastern Roman Empire) and large chunks of Asia besides. Gibbon's work ends with the cataclysmic year of 1453: the fall of Constantinople. Gibbon writes with great style as he sweeps through the ancient Mediterranean world, into the medieval period, and expands across empires, continents, and religions, all the time searching for the interdependence of events that have shaped Europe's history.

A theme that runs through the work is the clash between the ancient pagan religion of the Romans and the challenge given to it by the rise of Christianity. It is here that Decline and Fall finds its place as an important Enlightenment text. Enlightened thinkers sought to challenge the domination of Christianity over more ancient ways of thinking. The historian H. Chisick summarises this point as follows:

In a sense the Decline and Fall was a lament for the loss of the ordered, rational, tolerant, humanistic world of civic responsibility and classical republicanism, and its replacement with the mystical, other-worldly and inscrutable culture of Christianity…And like many works of historical scholarship, the Decline and Fall has as much to tell us about the period in which it was written as it does about the times it treats. (136).

Gibbon was greatly helped in his work by inheriting sufficient funds from his late father's estate in 1772 so that he could work full-time on his great literary adventure. Gibbon had set himself a herculean task, as reflected in his choice of this quote from the Roman author Livy (59 BCE to 17 CE) – who himself wrote a history of Rome – which Gibbon had printed on the title page of his finished book:

I see that I am like the people who are tempted by the shallow water along the beach to wade out to sea; the further I progress, the greater the depth, as though it were a bottomless sea, into which I am carried. I imagined that as I completed one part after another the task before me would diminish; as it is, it almost becomes greater.

(Robertson, 583)

Certainly, he amassed an impressive number of sources; Gibbon had over 6,000 books in his research library. Gibbon's entertaining writing style has great appeal, even if the historical accuracy is sometimes compromised. In this passage, for example, he lambasts Emperor Gallienus (r. 253-268):

In every art that he attempted, his lively genius was destitute of judgement, he attempted every art, except the important ones of war and government. He was a master of several curious, but useless sciences, a ready orator, an elegant poet, a skilful gardener, an excellent cook, and most contemptible prince.

(Bagnall, 2833)

The completed Decline and Fall eventually consisted of six volumes. Gibbon had amassed some 1.5 million words on his subject. The first volume was published in February 1776 and covers Rome from Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE) to Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE). The next two volumes came in 1781 and continued the story up to the reign of Romulus Augustulus, which ended in 476 CE, the traditional date for the end of the Western Roman Empire. The final three volumes came out in 1788 and tell the story of the Eastern Roman Empire, which ends with the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire. Despite the yardage required on people's bookshelves, the history quickly became a bestseller and was translated into a number of languages. The historian R. Robertson describes it as "the Enlightenment's greatest work of history" (xx), while H. Chisick describes Gibbon's book as "probably the greatest history in English" (135).

Reaction & Criticisms

At the time of publication, many theologians strongly objected to Gibbon's irreverent coverage of early Christianity, which is often additionally peppered with pithy and ironic comments in the abundant footnotes. Gibbon had his supporters, though, notably the Scottish philosopher and historian David Hume (1711-1776), who had also written a bestseller, his History of England, published between 1754 and 1762. Gibbon wrote a defence of his work in Vindication, published in 1779.

More modern critics point out that the work has dated badly in places, unsurprising considering the developments in the study of history since the 18th century and our ever-expanding knowledge enhanced by such specialised fields as archaeology, philology, and numismatics, as well as flourishing Byzantine and Islamic studies, to name but a few. Some do not agree with Gibbon's treatment of the Roman Empire as a coherent single empire. He is criticised for his rosy view of 2nd-century Rome as a 'Golden Age' and for his overly negative view of the Middle Ages when, in Gibbon's words, "the still voice of law and reason was seldom heard or obeyed" (Robertson, 587).

Still other critics point out the author's dependency on Latin sources and neglect of Byzantine and Arabic ones. Gibbon's conclusion that "the decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness…The story of its ruin is simple and obvious" (Bagnall, 2914) has been criticised as too simplistic a view. The rise of Christianity, the decline of Roman civic values, the increase in luxury, the overdependence on mercenary armies, and the restrictions of intellectual freedom are an impressive enough concoction but still cover only some parts of a complex and gradual cycle of interdependent events which resulted in the "fall" of Rome. Later historians have searched for external causes, such as invasions by Germanic peoples, besides the weaknesses within Rome itself.

Even the very idea of a "fall" has since been disputed, not least because the eastern half of the Roman Empire outlasted the western half by a millennium. Some have also argued that far from being in decline, the Roman Empire "was transformed in a vibrant age of challenging new ideas and new social, religious, and political structures" (Bagnall, 1951).

There are also criticisms that Gibbon is judging history rather than simply reporting it and that the former results in a bias in the latter. Gibbon is suggesting that the replacement of the Roman world by a Christian one is a step backward for humanity, a regression that was only being redressed in his own lifetime with the Enlightenment movement that stressed that human society should aspire to progress and a fairer world based on new principles established by science and philosophy, not religion.

In short, then, the Decline and Fall, because of its bias, omissions, and inaccuracies, is nowadays regarded as a rather quaint piece of history itself. Nevertheless, Gibbon's original intention for his work remains admirable, which was to examine how and why such an important empire in world history existed for so long. This type of analysis of history was very different from the usual history books, which were often nothing more than a collection of amusing and highly dubious stories about rulers (although Gibbon is sometimes guilty of this himself when dealing with the Byzantine emperors) or too focussed on military affairs to the exclusion of everything else. Another aspect of Gibbon's work which has inspired many historians that followed is the examination of history with the deliberate intention of assessing how such history affects our world in the present.

Death & Legacy

Gibbon lived in London from the early 1770s. In 1778, he took up residence with the Earl of Sheffield. Gibbon served as a Member of Parliament for Liskeard in Cornwall (although he seems never to have visited the place) and took minor office as part of the government of Lord North (Prime Minister from 1770 until 1782). He was, as a believer in "the natural equality of man" (Hampson, 153), in favour of the abolition of the slave trade. Gibbon moved back to Lausanne in 1783.

Gibbon suffered from ill health and obesity in his later years; he died in London on 16 January 1794 after a troublesome voyage from France. His remains were interred in the family mausoleum of the Earl of Sheffield, which is attached to the small church in the village of Fletching in Sussex. Gibbon's autobiographies, which covered various volumes, were published posthumously as a single volume, Memoirs of My Life and Writings.

Gibbons' Decline and Fall continued to exert great influence long after his death. Gibbon's presentation of a great civilization that declined and collapsed reminded Enlightenment thinkers that their own society was just as vulnerable to such a catastrophe, and this inspired them to continue to debate and find new approaches to politics, citizenship, and morality in order to ensure society did not degenerate but improved with each generation.

In the longer term, the idea of looking at the end of antiquity with the rather negative lens of "decline" in mind was an approach copied by many historians even as late as the second half of the 20th century. Gibbon was also influential on (some would say responsible for) the strong focus on the Western Roman Empire and the relative neglect of the Byzantine Empire by historians. Even Gibbon's negative presentation of certain emperors like Gallienus left a lasting and often incorrect picture, which persisted until relatively recently. On the other side, Gibbon's history was such an inspiration for historians and readers alike that one might argue it is only through his work that such revisions and improvements in our knowledge of ancient Rome have become possible. It is also worthy of note that in the 21st century, several historians have, in turn, begun to challenge the more positive view of Rome's final years and returned to the negative, albeit now a much more nuanced approach, that Gibbon first proposed.