Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester (l. 1602-1671), was a Parliamentarian commander during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). He led the Eastern Association army before the indecisive Second Battle of Newbury in 1644 led to recriminations, the formation of the New Model Army, and the removal of Manchester and others from direct military command. The earl remained at the forefront of the cause in his role as a member of the Committee of Both Kingdoms, Parliament's war cabinet.

Early Career

Edward was born in 1602, the eldest son of Sir Henry Montagu, 1st Earl of Manchester (c. 1563-1642). Edward's grandfather had been a mere barrister, but the family had rocketed up the social ladder during the reigns of James I of England (r. 1603-1625) and Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649). Sir Henry was made a peer in 1620, and he took the title 'Viscount of Mandeville'. Edward's mother was Catherine Spencer. Young Edward served the English Crown on campaign in Spain in 1623, and he returned to England to serve as a Member of Parliament for Huntingdon. Edward married five times and acquired his father's titles and estates following Sir Henry's death in 1642; he also became the Lord-Lieutenant of Northamptonshire and Huntingdonshire.

Civil War & the Eastern Association Army

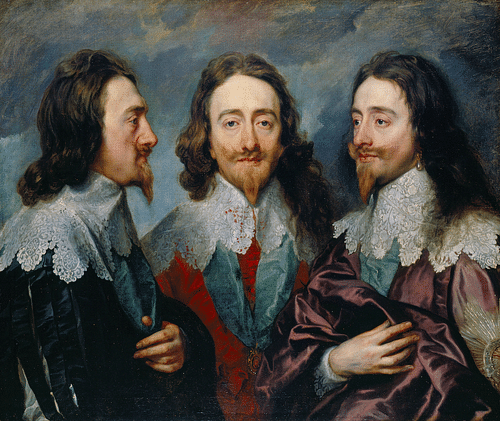

King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) considered himself an absolute monarch with absolute power and a divine right to rule, but his unwillingness to compromise with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms, led to a civil war in 1642. One of several sparks that lit the powder keg of civil war was the king's attempt to arrest five Members of Parliament on the charges of treason in January 1642. Edward Montagu, as Lord Mandeville, was a member of the House of Lords, and he, too, was arrested by his king on the same charge.

When war broke out, the 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) and 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) clashed in over 600 battles and sieges. Initially, the northern and western parts of England largely remained loyal to the monarchy, but the southeast, including London, was controlled by Parliament. The Parliamentarians also controlled the Royal Navy, a significant impediment to Charles receiving reinforcements from the Continent and Ireland.

The first large engagement of the war was the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire on 23 October 1642, with the two armies led by King Charles on the one side and Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex (l. 1591-1646) on the other. Like so many battles yet to come, it concluded with an indecisive result, and both sides survived to fight another day. Edward Montagu hardly covered himself in glory when he had led the regiment under his command away from the battle.

From August 1643, Edward Montagu, now the Earl of Manchester, led the Eastern Association Army which was drawn from recruits in Cambridgeshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Norfolk, Suffolk (and later Huntingdonshire and Lincolnshire). This army had 11 regiments (four were kept to guard the eastern counties while the other seven could be mobilised anywhere in the country). Besides being the overall commander of the Eastern Association army of around 3,000 men, Manchester personally commanded a regiment, the 'greencoats'. The earl frequently clashed with his talented cavalry commander Oliver Cromwell over just how many recruits were religious Independents. Cromwell was an Independent or Congregationalist while Manchester was a Presbyterian, and so the former had an altogether more liberal view on religious freedom.

At this early stage, few of the Parliamentarians wanted to oust the king, rather, they had concluded that he was being misadvised by his counsellors. It had, unfortunately, become necessary to use force to compel the king to listen to reason and accommodate some of the requests from his own Parliament. Manchester was certainly amongst the more moderate Parliamentarians, and, indeed, he would be accused of being far too moderate as the war dragged on.

Marston Moor

On 1 July 1644, the Parliamentarians were driven from their siege of York by the arrival of a large force under the command of Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria (l. 1619-1682). Not content with keeping control of this most vital of northern cities, Rupert then decided to attack the retreating enemy. This was a rash move, considering there were actually three Parliamentarian armies and, combined, they greatly outnumbered the Royalists, despite the arrival of a second army from York led by the Marquis of Newcastle.

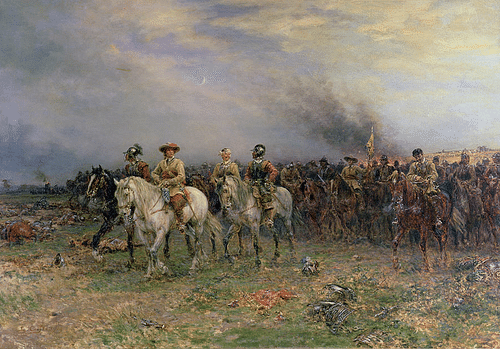

The Parliament's forces were led by the Earl of Manchester, Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven (d. 1661), and Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671). On 2 July, they turned around to face the enemy at the Battle of Marston Moor. It was one of the largest battles of the war and likely involved over 45,000 men. The Royalists fielded around 18,000 men, of which around 6,000 were cavalry, while the Parliamentarians had up to 28,000 men. The Earl of Manchester's cavalry led by Sir David Leslie and Oliver Cromwell performed particularly well, the Parliamentarians won a decisive victory, and with the surrender of York two weeks later, they now controlled almost all of the north of England. Cromwell was now Manchester's Lieutenant-General of Horse, and this rising new military star would soon become a serious challenge to the earl's own position of command.

The Dishonour of Newbury

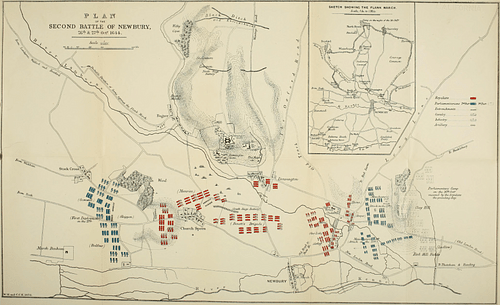

The Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644 brought only another indecisive result that ensured the English Civil Wars rolled on. The Parliamentarians enjoyed a numerical advantage of 2:1, but the lack of coordination between their commanders cost them a decisive victory. Manchester's lack of purpose at the battle came in for particular criticism.

Three Parliamentarian armies converged on Berkshire. The three respective commanders were the Earl of Essex, Sir William Waller (1597-1668), and Manchester. Essex considered himself above the other two, but neither of these was willing to take a subordinate position to anyone. A command committee was formed with all three leaders and selected staff officers. Then Essex became ill and was obliged to withdraw.

The Roundheads and Cavaliers clashed for the umpteenth time, but the former's well-chosen defensive position did much to compensate for their numerical disadvantage. Waller and Manchester had planned a pincer movement to close on Charles' army from two sides, but their lack of coordination meant that the king was not obliged to fight continuously on two fronts. Manchester was subsequently accused of being too slow to engage his troops on his side of the pincer. It may have been that Manchester was waiting to have news that Waller was fully engaged a couple of miles distant before committing his smaller force to the fray. If he had committed before Waller was occupying the enemy, then his army would have been quickly overwhelmed by the entire Cavalier army. Manchester's army did cross the River Lambourn and made inroads into the enemy positions, but it was then driven back by the Royalist infantry reserve. Even the Parliamentarians' star cavalry commander Oliver Cromwell seems to have had an off day since he did not gain his usual successes against the opposition cavalry.

Overnight, Charles withdrew his army, and Manchester faced further criticism for not pursuing them with any vigour. The result of the battle was a draw when it might so easily have been a resounding Parliamentarian victory. An inquiry was held as to why this opportunity had been lost. Manchester was not the only commander to come in for criticism, but he had also to face additional rumours that he was not as loyal to the cause as he was expected to be. Manchester's position was not helped by the king having made approaches to him to act as a mediator between him and Parliament or by Manchester's own declarations that however many times they defeated the royal army, Charles would still be the king. Manchester also noted that a few severe losses by the Parliamentarians would end their cause, and this perhaps explains his caution on the battlefield. He stated:

The king need not care how oft he fight, but it concerns us to be wary, for in fighting we venture all to nothing. If we fight a hundred times and beat him ninety-nine times, he will be the King still. But if he beat us once, or the last time, we shall be hanged, we shall lose our estates, and our posterities be undone.

(Hunt, 149-50)

The earl returned to the theme of religion, another important difference between himself and Cromwell and an interference in the successful running of the Parliamentary army:

Colonel Cromwell raising of his regiments makes choice of his officers, not such as were soldiers or men of estate, but such as were common men, poor and of mean parentage, only he would give them the title of godly precious men; yet his common practise was to cashier honest gentlemen and soldiers that were stout in the cause as I conceive, witness those that did suffer in that case…If you look upon his own regiment of horse see what a swarm there is of those that call themselves the godly; some of them profess they have seen visions and had revelations.

(Hunt, 151)

Manchester defended his military decisions at Newbury and blamed the lack of a positive result on his cavalry commander Cromwell, questioning his loyalty. The earl believed a compromise could still be reached with the king and noted his belief that Cromwell was bitterly against the aristocracy and would have it swept if away if he could, a belief that was endorsed by the House of Lords. When the motion went to the lower House of Commons, Cromwell took the opportunity to defend himself and attack Manchester:

…his Lordship's miscarriage in these particulars were neither through accidents (which could not be helped) nor through his improvidence only, but through his backwardness to all action, and [I] had some reason to conceive that that backwardness was not (merely) from dullness or indisposedness to engagement, but (withal) from some principle of unwillingness in his Lordship to have this war prosecuted unto a full victory, and a design or desire to have it ended by accommodation (and that) on some such terms to which it might be disadvantageous to bring the King too low. To the end therefore that (if it were so) the state might not be further deceived in their expectation from their Army, I did (in the faithful discharge of my duty to the Parliament and kingdom) freely discover those my apprehensions, and what grounds I had for them.

(Hunt, 149)

The Committee of Both Kingdoms

The fallout of Newbury ultimately led to the formation of the New Model Army in the first months of 1645. This was a more professional Parliamentarian force with a well-defined and unified command structure. To make sure commanders of its 24 regiments were not in their position simply because of their titles, in April Parliament passed the Self-Denying Ordinance, a motion which forbade any of its members from also being a military commander. Waller, Essex, and Manchester were all casualties of this policy. Overall command of the New Model Army was given to a talented and experienced campaigner: Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671).

The Earl of Manchester no longer had a field command, but he was still heavily involved in the Parliamentarian cause. From February 1644, Parliament ran the war through the Committee of Both Kingdoms with its membership drawn from selected members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Meeting daily in some periods, one of the committee's functions was to direct the New Model Army and decide when, where, and which regiments fought. Manchester was a member of this all-powerful committee.

Retirement & Death

The Model Army went on to win a great victory at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire in June 1645. Naseby was followed by more victories, including the capture of Bristol, and King Charles was obliged to flee to Scotland. When Charles was handed back and put on trial, Manchester opposed this process and retired from public life. The king was found guilty of treason and executed in January 1649, but the republic headed by Cromwell was short-lived. In May 1660, the Restoration saw Charles' son become Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), and in reward for his withdrawal from the extremist Republican juggernaut and support of George Monck (1608-1670) and his scheme to reinstate the royal institution, the Earl of Manchester was given another load of titles for his already impressive collection, including being made a Knight of the Order of the Garter. The earl died on 5 May 1671 and was buried in Kimbolton Church, Huntingdonshire.