The Egyptian Empire rose during the period of the New Kingdom (c. 1570- c. 1069 BCE), when the country reached its height of wealth, international prestige, and military might. The empire stretched from modern-day Syria in the north to modern-day Sudan in the south and from the region of Jordan in the east to Libya in the west.

Since the empire rose and fell in the course of the New Kingdom, historians refer to the period as either the New Kingdom or the Egyptian Empire interchangeably.

Egyptian history is divided by later scholars into eras of “kingdoms” and “intermediate periods”; kingdoms were times of a strong central government and a unified nation while intermediate periods were eras of a weak central government and disunity. The New Kingdom emerged from the time known as the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782- c. 1570 BCE) in which the country was divided between a foreign Semitic people known as the Hyksos holding power in northern Lower Egypt, the Nubians ruling to the south in Upper Egypt, and the city of Thebes in the middle representing the traditional Egyptian government.

The Theban king Ahmose I (c. 1570- c. 1544 BCE) drove the Hyksos out of Egypt and defeated the Nubians, uniting Egypt under his rule from Thebes. In his early campaigns, Ahmose I created buffer states around Egypt's borders to prevent any other foreign power from gaining a foothold in the country as the Hyksos had. In doing so, he initiated the policy of conquest which would be followed by his successors and give rise to the empire of Egypt.

This period is the most famous in Egyptian history. Egypt's best-known monarchs such as Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, Ramesses II (the Great), and Ramesses III all reigned during this time and some of the most famous monuments and temples – such as the Colossi of Memnon and the Temple of Amun at Karnak – were built.

The empire flourished through the reign of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) when invasions (primarily by the Sea Peoples), over-spending which depleted the treasury, corruption of government officials, loss of faith in the traditional role of the king, increased power of the priesthood, and a decline in its international prestige all contributed to its fall. In its time, however, it was among the most powerful and prestigious empires of the ancient world.

The Hyksos in Egypt

The Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) during the 12th Dynasty is considered Egypt's “golden age” when cultural and artistic achievements reached their height. During the 13th Dynasty, however, the kings were weaker and more concerned with their own pursuits and court intrigues than the good of the country. During this time, the Hyksos were able to establish themselves at Avaris in Lower Egypt and steadily consolidated their presence until they were able to wield significant political- and military power. The Middle Kingdom fell as the Egyptian central government grew weaker and both the Hyksos in the north and the Nubians in the south grew stronger, initiating the Second Intermediate Period.

Later scribes of the New Kingdom would characterize the time of the Hyksos as an “invasion” and other writers, picking up on this, perpetuated that myth. The Hyksos never invaded Egypt, however; they were initially traders who saw an opportunity to establish themselves in a neglected region of Egypt and took it. Contrary to later reports, the Hyksos were not enemies of Egypt who rampaged through the country burning and looting the temples.

There is ample evidence, rather, that the Hyksos admired Egyptian culture and emulated the Egyptians in many ways. Trade connections between the Hyksos in the north, the Nubians in the south, and Thebes were well-established and the only evidence of the Hyksos destroying temples or sacking cities comes long after their arrival in the land and is thought to have been provoked by individual cities of Lower Egypt or by Thebes. It is also a myth that the Hyksos ruled all of Lower Egypt; their power was limited to just below the Delta region.

Trade went on evenly between the Hyksos, Egyptians, and Nubians until the government at Thebes grew tired of feeling like guests in their own country. The Theban king Seqenenra Taa (also known as T'aO, c. 1580 BCE), interpreted a message from the Hyksos king Apepi – which was probably a request to curtail the Theban practice of hippo hunting – as a challenge to his authority and launched a campaign against the town of Avaris. Ta'O was killed in battle but his cause was taken up by his son Kamose and then by Ahmose I who defeated the Hyksos and unified Egypt.

Rise of the Empire

Ahmose I conquered Avaris, drove the Hyksos survivors into the Levant and then pursued them up through Syria. In doing so, he naturally conquered those regions for Egypt and installed his own officials to govern them; this was the beginning of the Egyptian Empire. Ahmose I established the policy of creating buffer states around Egypt's borders so that an “invasion” such as that of the Hyksos would never be possible again. After defeating the Hyksos, Ahmose I marched south and drove the Nubians back beyond the traditional borders, thus enlarging Egypt's territory in three directions – south, east, and north – which included the profitable region of the Levant.

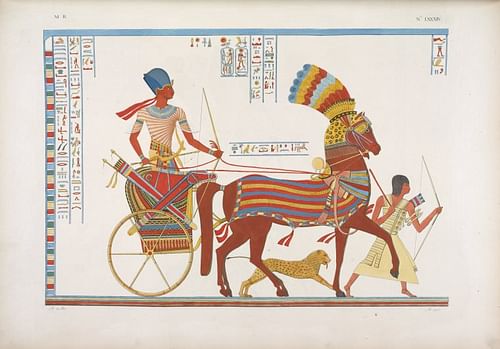

Although the Hyksos were later vilified, they improved Egyptian culture in a number of ways and, significantly, improved their weaponry, too. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos, the Egyptians had no knowledge of the horse or horse-drawn chariot; they were still using the single-arched bow, and were equipped with swords which were not always reliable. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson comments on Hyksos' contributions:

The Hyksos, being from western Asia, brought the Egyptians into contact with the peoples and the culture of that region as never before and introduced them to the horse-drawn war chariot; to a composite bow made from wood reinforced with strips of sinew and horn, a more elastic weapon with a greater range than their own simple bow; to a scimitar-shaped sword, called the Khopesh, and to a bronze dagger with a narrow blade cast in one piece with the tang. The Egyptians developed this weapon into a short sword. (60).

The Khopesh (also given as Khepesh) sword was cast entirely of bronze and the handle was then wound with hide and cloth and, with more expensive blades, ornamented. This curved sword was much more effective than any the Egyptians had used in the past. The war chariot, manned by archers with the new composite bow and a large quiver attached to the side, would prove one of Egypt's most significant military assets, and the battle axe, made of bronze attached to a haft, was far more effective than the flint or copper axes bound to wooden shafts used in the past. These would be the weapons of the New Kingdom empire and would be used by a new kind of military.

The Armies of the Empire

The first standing army in Egypt was established by Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) of the 12th Dynasty in the Middle Kingdom. Prior to this time, the army was comprised of conscripts sent to the king by regional governors (called nomarchs) from their districts (nomes) who were often more loyal to their home-ruler and region than the king of the country. These early armies marched under their own banners and elevated their regional cult gods. Amenemhat I cut the power of the nomarchs by creating a professional army with a chain of command that placed power in the king's hands and was overseen by his vizier.

The army Ahmose I mobilized against the Hyksos was made up of professionals, conscripts, and mercenaries like the Medjay warriors but under the reign of his son, Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE) this army would be extensively trained and further equipped with the best weapons available at the time. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick notes:

By the New Kingdom, the Egyptian army had begun to adopt the superior weapons and equipment of their enemies - the Syrians and Hittites. The triangular bow, the helmet, chain-mail tunics, and the Khepesh sword became standard issue. Equally, the quality of the bronze improved as the Egyptians experimented with different proportions of tin and copper. (466).

Not only were the weapons of the army new and improved but so was the structure of the military itself. Between the time of Amenemhat I and Ahmose I the military had remained more or less the same. Weaponry and military training had improved but not dramatically. Under the reign of Amenhotep I, though, this would change as Egyptologist Margaret Bunson explains:

The army was no longer a confederation of nome levies but a first-class military force ... organized into divisions, both chariot forces and infantry. Each division numbered approximately 5,000 men. These divisions carried the names of the principal deities of the nation. (170).

Unlike the early army which went to battle under the banners of their nomes and clans, the New Kingdom army fought for the welfare of the entire country, bearing the standards of the universal gods of Egypt. The king was the commander-in-chief of the armed forces with his vizier and subordinates handling the logistics and supply lines. The chariot divisions, in which the pharaoh rode, were directly under his command and divided into squadrons with their own captain. There were also mercenary forces, like the Medjay, who served as shock troops.

The Age of Imperial Egypt

These were the troops who forged and then maintained the Egyptian Empire. Amenhotep I continued the policies of Ahmose I and each pharaoh who came after him did the same. Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) put down rebellions in Nubia and expanded Egypt's territories in the Levant and Syria. Nubia was especially prized by the Egyptians for their gold mines and, in fact, the region took its name from the Egyptian word for 'gold' – nub. Little is known of his successor, Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE) because his reign is overshadowed by the impressive era of queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE).

Hatshepsut is not only the most successful female ruler in Egypt's history but among the most remarkable leaders of the ancient world. She broke with the tradition of a patriarchal monarchy with no evidence of rebellion on the part of her subjects or the court and established a reign which enriched Egypt financially and culturally without engaging in any extensive military campaigns.

Although there is evidence that she commissioned military expeditions early in her reign, the remainder was peaceful and focused on Egypt's infrastructure, building projects, and trade. She re-established contact with the Land of Punt – an almost mythical land of riches – which supplied Egypt with many of the luxury goods the upper classes came to covet as well as necessary items for the worship of the gods (such as incense) and the cosmetics industry (oils and scented flowers).

When Hatshepsut died, she was succeeded by Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) who, possibly in an effort to prevent future women from emulating her, had Hatshepsut's name erased from monuments. He would have done this in order to maintain the tradition of a male sovereign, not because he had anything against the queen, and he left her name intact inside her mortuary temple and elsewhere out of the public eye. Even so, later kings knew nothing of her accomplishments and she would not be known to history again for over 2,000 years.

Thutmose III should not be remembered for this one action, however, as he proved himself an able and efficient ruler and a brilliant military leader. Historians have often referred to him as the “Napoleon of Egypt” for his success in battle as he fought 17 campaigns in 20 years and, unlike Napoleon, he was victorious in all of them. He also encouraged and extended trade and was a man of culture who helped preserve Egypt's history.

The foreign and domestic policies of Thutmose III enriched Egypt and expanded its borders, providing the country with a stable economy and a growing international reputation. By the time of the reign of Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE), Egypt was among the wealthiest and most powerful in the world. Amenhotep III was a brilliant administrator and diplomat whose prosperous reign established Egypt firmly in what historians refer to as the “Club of the Great Powers” – which included Babylonia, Assyria, Mittanni, and the Land of the Hatti (Hittites) – all of whom were joined in peaceful relations through trade and diplomacy.

Foreign kings wrote regularly to Amenhotep III asking for gold and favors, which he freely granted, and countries were eager to trade with Egypt because of its vast resources and considerable strength. The Egyptian army at this time was formidable and alliances were quick to be made. Wealth flowed into the royal treasury from beyond Egypt's borders and Amenhotep III could afford to pay large crews of workers to erect his temples and monuments. He built so many of these, in fact, that later historians thought he must have ruled for over 100 years to have accomplished all he had; in reality, he was simply an exceptionally able statesman.

Amenhotep III's son and successor was Amenhotep IV who, in the fourth or fifth year of his reign, changed his name to Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) and abolished the traditional religious practices of Egypt. Although Akhenaten is frequently depicted by modern day writers as a great religious visionary and an exceptional king he was actually neither. His religious reforms were most likely a political maneuver to decrease the power of the Cult of Amun which, by his time, was almost as powerful as the king, and his attention to rule was so minimal that his wife, Nefertiti, took over administrative duties and correspondence with other nations.

The friction between the Cult of Amun and royalty started during the period of the Old Kingdom when the kings of the 4th Dynasty elevated the sect and gave them tax-exempt status in exchange for performing the necessary mortuary rituals at the Giza complex. Since they were tax-exempt, all the produce from their lands went to them directly – not to the government – and so they were able to amass considerable wealth. From the Old Kingdom on, the cult only grew in power and so it is probable that Akhenaten's “reforms” were motivated far more by politics and greed than any divine vision of a one true god.

Under the reign of Akhenaten, the capital was moved from Thebes to a new city, Akhetaten, designed and built by the king and dedicated to his personal god. The temples in all the cities and towns were closed and religious festivals abolished except those venerating his god, the Aten. The Egyptian economy relied heavily on religious practices as the temples were the centers of the community and employed a large staff.

Further, crafts-people who made statuary, amulets, and other religious artifacts were also put out of work. The central cultural value of Egypt – ma'at (harmony and balance) – which was the foundation of the religion and the society was ignored by Akhenaten's administration and so were the diplomatic and commercial ties with other powers.

Akhenaten's successor was Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE) who was in the process of restoring Egypt to its former status when he died young. His work was completed by Horemheb (1320-1295 BCE) who erased Akhenaten's name from history and destroyed his city. Horemheb succeeded in restoring Egypt but it was nowhere near the strength it had been prior to Akhenaten's reign.

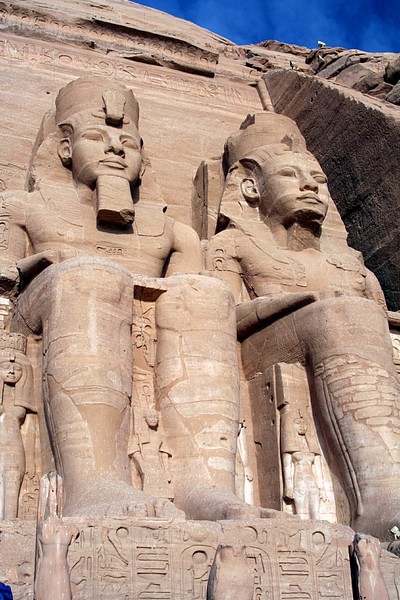

During the 19th Dynasty which followed Horemheb, the most famous pharaoh in Egypt's history would claim to have finally restored the country to power: Ramesses II (the Great, 1279-1213 BCE). Ramesses II is not only the best-known pharaoh in the present day but also in antiquity thanks to his talent for self-promotion and the skills of his vizier, Khay, who ensured that the king's name would endure through monuments, temples, and towering statuary honoring him.

Ramesses II may not have completely brought Egypt back to the level of power it had known under Amenhotep III but he certainly came close. He re-established ties with the other great powers, signed the first peace treaty in the world with the Hittites following the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BCE), and, although he had himself depicted regularly as a great warrior-king, concentrated most of his reign on domestic policies, trade, and diplomacy. Thutmose III was actually the most skilled military leader of the New Kingdom, not Ramesses II, but the image of the pharaoh as a mighty warrior was a long-established tradition in Egypt symbolizing the king's powers even if a particular monarch was actually more skilled in other areas.

Decline & Fall

The 19th Dynasty continued the successes of the 18th but, during the 20th Dynasty, the empire began to decline. Ramesses II and his successor, Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE) had both defeated invasions by the Sea Peoples – a coalition of different tribes who were responsible for weakening and destroying a number of civilizations at this time – but had not crippled their power. In the 20th Dynasty, under the reign of Ramesses III, the Sea Peoples returned in force and the king had no choice but to mobilize his army and mount a defense.

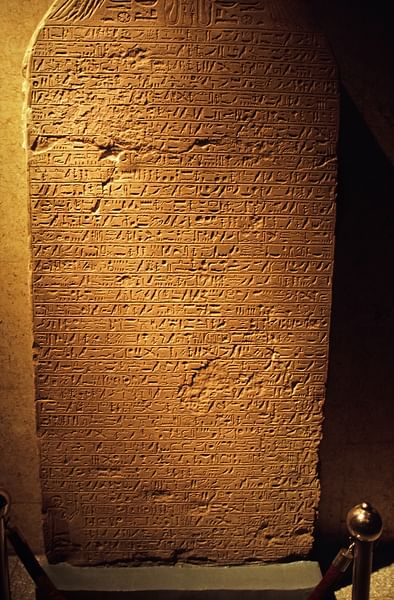

Ramesses III defeated the Sea Peoples just as his predecessors had but the cost in lives and resources was tremendous. In keeping with the Egyptian practice of elevating the numbers of enemies slain in battle while minimizing their own losses, official records only record the glorious victories of the defense of Egypt. Evidence of problems arising afterwards, however, indicates that a loss of labor resulted in less grain production and a struggling economy. The cost of the war had also depleted the treasury and trade relations with other powers were suffering because Egypt did not have the kinds of resources as before and, also, these other powers were dealing with their own difficulties resulting from raids by the Sea Peoples and others.

At this same time, the Cult of Amun was again as powerful as it had been prior to Akhenaten's attempt to destroy it. The high priest at Thebes was increasingly given as much, if not more, respect than the king, thus weakening the monarchy. The empire's problems were clearly manifested in the worker's strike of 1159 BCE at Deir el-Medina – the first recorded strike in the world – when the wages for the tomb builders were late and the local officials were helpless in rectifying the problem.

One report from the time cites an official telling the workers that he would give them their grain if he had any but there was nothing he could do. Officials also had no idea how to handle the strike itself – nothing like it had ever happened before – and so they more or less did nothing. The underlying problem was that the concept of harmony – embodied in ma'at – had been ignored and the king was no longer able to keep the balance required to govern effectively.

Ramesses III was the last good pharaoh of the New Kingdom. The problems which would lead to the rapid decline of the empire manifested themselves only toward the end of his reign. After his reign, the country entered what is known as the Ramessid Period when Ramesses IV through Ramesses XI presided over the steady decline of the empire.

By the time of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE), respect for the pharaoh was at an all-time low as the economy floundered, trade with other countries became more difficult, the army was allowed to stagnate, and Egypt's international standing became a memory. The poor economy encouraged tomb robbing and wide-spread corruption among police, magistrates, and government officials who no longer respected the social hierarchy or the religious and cultural values which had sustained Egypt for so long.

A letter from a general during the reign of Ramesses XI exemplifies how fragmented Egyptian society had become by this time when he asks, “As for pharaoh, whose superior is he after all?” (van de Mieroop, 257). This kind of question would have been unthinkable at the height of the Egyptian Empire but, as the priests of Amun became more powerful and the king became weaker, the monarch came to matter less and less to the people.

The 20th Dynasty – and the Egyptian Empire - ended with the death of Ramesses XI. The country was, by this time, divided between rule by the pharaoh in Lower Egypt and by the High Priest of Amun at Thebes in Upper Egypt. Ramesses XI's successor, Smendes (1077-1051 BCE), would attempt to reign like the pharaohs of the past but, in reality, was a co-ruler with the high priest Herihor of Thebes (c. 1074 BCE) at the beginning of the era known as the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE).

The Egyptian literary work The Report of Wenamun is set during this period and describes the difficulties of an official who is sent on a mission to the Levant to buy wood for the restoration of the Barque of Amun. At the height of the empire, this task would have posed no problems but, the author makes clear, once Egypt had lost its balance and fallen in status with other powers, even the simplest undertaking could become an ordeal. Wenamun is robbed, insulted, ignored, and even resorts to robbery himself.

Like the letter questioning the king's value, the events depicted in The Report of Wenamun would have been unimaginable during the golden days of Egypt's empire. The time of Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and Ramesses II was over and Egypt's later periods would see few kings like them and know nothing like the grandeur of the Egyptian Empire.