The government of ancient Egypt was a theocratic monarchy as the king ruled by a mandate from the gods, initially was seen as an intermediary between human beings and the divine, and was supposed to represent the gods' will through the laws passed and policies approved.

A central government in Egypt is evident by c. 3150 BCE when King Narmer unified the country, but some form of government existed prior to this date. The Scorpion Kings of the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-c. 3150 BCE) obviously had a form of monarchial government, but exactly how it operated is not known.

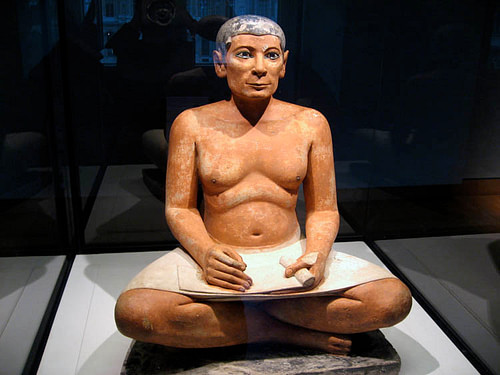

Egyptologists of the 19th century CE divided the country's history into periods in order to clarify and manage their field of study. Periods in which there was a strong central government are called 'kingdoms' while those in which there was disunity or no central government are called 'intermediate periods.' In examining Egyptian history one needs to understand that these are modern designations; the ancient Egyptians did not recognize any demarcations between time periods by these terms. Scribes of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2040-1782 BCE) might look back on the time of the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) as a "time of woe" but the period had no official name.

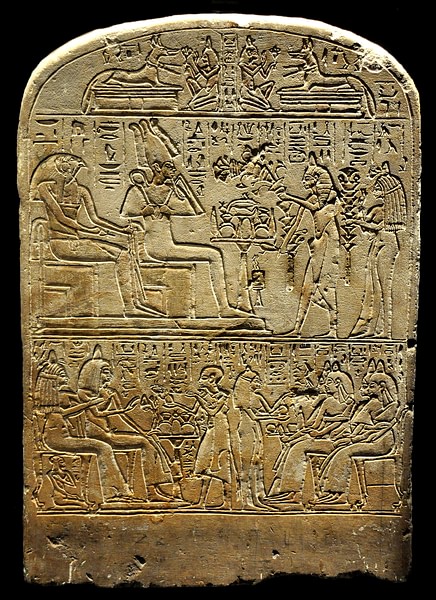

The way in which the government worked changed slightly over the centuries, but the basic pattern was set in the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2890 BCE). The king ruled over the country with a vizier as second-in-command, government officials, scribes, regional governors (known as nomarchs), mayors of the town, and, following the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 - c.1570 BCE), a police force. From his palace at the capital, the king would make his pronouncements, decree laws, and commission building projects, and his word would then be implemented by the bureaucracy which became necessary to administer rule in the country. Egypt's form of government lasted, with little modification, from c. 3150 BCE to 30 BCE when the country was annexed by Rome.

EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD & OLD KINGDOM

The ruler was known as a 'king' up until the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570-1069 BCE) when the term 'pharaoh' (meaning 'Great House,' a reference to the royal residence) came into use. The first king was Narmer (also known as Menes) who established a central government after uniting the country, probably by military means. The economy of Egypt was based on agriculture and used a barter system. The lower-class peasants farmed the land, gave the wheat and other produce to the noble landowner (keeping a modest portion for themselves), and the landowner then turned the produce over to the government to be used in trade or in distribution to the wider community.

Under the reign of Narmer's successor, Hor-Aha (c. 3100-3050 BCE) an event was initiated known as Shemsu Hor (Following of Horus) which would become standard practice for later kings. The king and his retinue would travel through the country and thus make the king's presence and power visible to his subjects. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson comments:

The Shemsu Hor would have served several purposes at once. It allowed the monarch to be a visible presence in the life of his subjects, enabled his officials to keep a close eye on everything that was happening in the country at large, implementing policies, resolving disputes, and dispensing justice; defrayed the costs of maintaining the court and removed the burden of supporting it year-round in one location; and, last but by no means least, facilitated the systematic assessment and levying of taxes. A little later, in the Second Dynasty, the court explicitly recognized the actuarial potential of the Following of Horus. Thereafter, the event was combined with a formal census of the country's agricultural wealth. (44-45)

The Shemsu Hor (better known today as the Egyptian Cattle Count) became the means whereby the government assessed individual wealth and levied taxes. Each district (nome) was divided into provinces with a nomarch administering overall operation of the nome, and then lesser provincial officials, and then mayors of the towns. Rather than trust a nomarch to accurately report his wealth to the king, he and his court would travel to assess that wealth personally. The Shemsu Hor thus became an important annual (later bi-annual) event in the lives of the Egyptians and, much later, would provide Egyptologists with at least approximate reigns of the kings since the Shemsu Hor was always recorded by reign and year.

Tax collectors would follow the appraisal of the officials in the king's retinue and collect a certain amount of produce from each nome, province, and town, which went to the central government. The government, then, would use that produce in trade. Throughout the Early Dynastic Period, this system worked so well that by the time of the Third Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2670-2613 BCE) building projects requiring substantial costs and an efficient labor force were initiated, the best-known and longest-lasting being The Step Pyramid of King Djoser. During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) the government was wealthy enough to build even larger monuments such as the pyramids of Giza.

The most powerful person in the country after the king was the vizier. There were sometimes two viziers, one for Upper and one for Lower Egypt. The vizier was the voice of the king and his representative and was usually a relative or someone very close to the monarch. The vizier managed the bureaucracy of the government and delegated the responsibilities as per the orders of the king. During the Old Kingdom, the viziers would have been in charge of the building projects as well as managing other affairs.

Toward the end of the Old Kingdom, the viziers became less vigilant as their position became more comfortable. The enormous wealth of the government was going out to these massive building projects at Giza, at Abusir, Saqqara, and Abydos and the priests who administered the temple complexes at these sites, as well as the nomarchs and provincial governors, were becoming more and more wealthy. As their wealth grew, so did their power, and as their power grew, they were less and less inclined to care very much what the king thought or what his vizier may or may not have demanded of them. The rise in the power of the priests and nomarchs meant a decline in that of the central government which, combined with other factors, brought about the collapse of the Old Kingdom.

FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD & MIDDLE KINGDOM

The kings still ruled from their capital of Memphis at the beginning of the First Intermediate Period, but they had very little actual power. The nomarchs administered their own regions, collected their own taxes, built their own temples and monuments in their honor, and commissioned their own tombs. The early kings of the First Intermediate Period (7th-10th dynasties) were so ineffectual that their names are hardly remembered and their dates are often confused. The nomarchs, on the other hand, grew steadily in power. Historian Margaret Bunson explains their traditional role prior to the First Intermediate Period:

The power of such local rulers was modified in times of strong pharaohs, but generally they served the central government, accepting the traditional role of being First Under The King. This rank denoted an official's right to administer a particular nome or province on behalf of the pharaoh. Such officials were in charge of the region's courts, treasury, land offices, conservation programs, militia, archives, and store-houses. They reported to the vizier and to the royal treasury on affairs within their jurisdiction. (103)

During the First Intermediate Period, however, the nomarchs used their growing resources to serve themselves and their communities. The kings of Memphis, perhaps in an attempt to regain some of their lost prestige, moved the capital to the city of Herakleopolis but were no more successful there than at the old capital.

C. 2125 BCE an overlord known as Intef I rose to power at a provincial city called Thebes in Upper Egypt and inspired his community to rebel against the kings of Memphis. His actions would inspire those who succeeded him and finally result in the victory of Mentuhotep II over the kings of Herakleopolis c. 2040 BCE, initiating the Middle Kingdom.

Mentuhotep II reigned from Thebes. Although he had ousted the old kings and begun a new dynasty, he patterned his rule on that of the Old Kingdom. The Old Kingdom was looked back on as a great age in Egypt's history, and the pyramids and expansive complexes at Giza and elsewhere were potent reminders of the glory of the past. One of the old patterns he kept, which had been neglected during the latter part of the Old Kingdom, was duplication of agencies for Upper and Lower Egypt as Bunson explains:

In general, the administrative offices of the central government were exact duplicates of the traditional provincial agencies, with one significant difference. In most periods the offices were doubled, one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt. This duality was carried out in architecture as well, providing palaces with two entrances, two throne rooms, etc. The nation viewed itself as a whole, but there were certain traditions dating back to the legendary northern and southern ancestors, the semi-divine kings of the predynastic period, and to the concept of symmetry. (103)

The duplication of agencies not only honored the north and the south of Egypt equally but, more importantly for the king, kept tighter control of both regions. Mentuhotep II's successor, Amenemhat I (c. 1991 - c.1962 BCE), moved the capital to the city of Iti-tawy near Lisht and continued the old policies, enriching the government quickly enough to begin his own building projects. His shifting of the capital from Thebes to Lisht may have been an attempt at further unifying Egypt by centering the government in the middle of the country instead of toward the south. In an effort which curbed the power of the nomarchs, Amenemhat I created the first standing army in Egypt directly under the king's control. Prior to this, armies were raised by conscription in the different districts and the nomarch then sent his men to the king. This gave the nomarchs a great degree of power as the men's loyalties lay with their community and regional ruler. A standing army, loyal first to the king, encouraged nationalism and stronger unity.

When it came to collecting taxes, in the form of a proportion of farm produce, we must assume a network of officials operated on behalf of the state throughout Egypt. There can be no doubt that their efforts were backed up by coercive measures. The inscriptions left by some of these government officials, mostly in the form of seal impressions, allow us to re-create the workings of the treasury, which was by far the most important department from the very beginning of Egyptian history. Agricultural produce collected as a government revenue was treated in one of two ways. A certain proportion went directly to state workshops for the manufacture of secondary products - for example, tallow and leather from cattle; pork from pigs; linen from flax; bread, beer, and basketry from grain. Some of these value-added products were then traded and exchanged at a profit, producing further government income; other were redistributed as payment to state employees, thereby funding the court and its projects. The remaining portion of agricultural produce (mostly grain) was put into storage in government granaries, probably located throughout Egypt in important regional centers. Some of the stored grain was used in its raw state to finance court activities, but a significant share was put aside as emergency stock, to be used in the event of a poor harvest to help prevent wide-spread famine. (45-46)

The nomarchs of the Middle Kingdom cooperated fully with the king in sending resources, and this was largely because their autonomy was now respected by the throne in a way it had not been previously. Egyptian art during the Middle Kingdom period shows a much greater variation than that of the Old Kingdom which suggests a greater value placed on regional tastes and distinct styles rather than only court-approved and -regulated expression. Further, letters from the time make clear that the nomarchs were accorded a respect by the 12th Dynasty kings, which they had not known during the Old Kingdom. Under the reign of Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) the power of the nomarchs was decreased and the nomes were reorganized. The title of nomarch disappears completely from the official records during Senusret III's reign suggesting that it was abolished. Provincial rulers no longer had the freedoms they had enjoyed earlier but still benefitted from their position; they were now just more firmly under the control of the central government.

The 12th Dynasty of Egypt's Middle Kingdom (c. 2040-1802 BCE) is considered the 'golden age' of government, art, and Egyptian culture when some of the most significant literary and artistic works were created, the economy was robust, and a strong central government empowered trade and production. Mass production of artifacts such as statuary (shabti dolls, for example) and jewelry during the First Intermediate Period had led to the rise of mass consumerism which continued during this time of the Middle Kingdom but with greater skill producing works of higher quality. The 13th Dynasty (c. 1802-c. 1782 BCE) was weaker than the 12th. The comfort and high standard of living of the Middle Kingdom declined as regional governors again assumed more power, priests amassed more wealth, and the central government became increasingly ineffective. In the far north of Egypt, at Avaris, a Semitic people had settled around a trading center and, during the 13th Dynasty, these people grew in power until they were able to assert their own autonomy and then expand their control of the region. These were the Hyksos ('foreign kings') whose rise signals the end of the Middle Kingdom and the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt.

SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD & NEW KINGDOM

The later Egyptian writers characterized the time of the Hyksos as chaotic and claimed they invaded and destroyed the country. Actually, the Hyksos admired Egyptian culture and adopted it as their own. Although they did conduct raids on Egyptian cities such as Memphis, carrying statuary and monuments back to Avaris, they dressed as Egyptians, worshiped Egyptian gods, and incorporated elements of Egyptian government in their own.

The Egyptian government at Itj-tawi near Lisht could no longer control the region and abandoned Lower Egypt to the Hyksos, moving the capital back to Thebes. As the Hyksos gained power in the north, the Kushites advanced in the south and took back lands Egypt had conquered under Senusret III. The Egyptians at Thebes tolerated this situation until c. 1580 BCE when the Egyptian king Seqenenra Taa (also known as Ta'O) felt he had been insulted and challenged by the Hyksos king Apepi and attacked. This initiative was picked up and furthered by his son Kamose (c. 1575 BCE) and finally by his brother Ahmose I (c. 1570-c. 1544 BCE), who defeated the Hyksos and drove them out of Egypt.

The victory of Ahmose I begins the period known as the New Kingdom of Egypt, the best-known and most well-documented era in Egyptian history. At this time, the Egyptian government was reorganized and reformed slightly so that now the hierarchy ran from the pharaoh at the top, to the vizier, the royal treasurer, the general of the military, overseers (supervisors of government locations like worksites) and scribes who kept the records and relayed correspondence.

The New Kingdom also saw the institutionalization of the police force which was begun under Amenemhet I. His early police units were members of the Bedouin tribes who guarded the borders but had little to do with keeping domestic peace. The New Kingdom police were Medjay, Nubian warriors who had fought the Hyksos with Ahmose I and were rewarded with the new position. The police were organized by the vizier under the direction of the pharaoh. The vizier would then delegate authority to lower officials who managed the various patrols of State Police. Police guarded temples and mortuary complexes, secured the borders and monitored immigration, stood watch outside royal tombs and cemeteries, and oversaw the workers and slaves at the mines and rock quarries. Under the reign of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) the Medjay were his personal bodyguards. For most of their tenure, though, they kept the peace along the borders and intervened in citizen's affairs at the direction of a higher official. In time, some of these positions came to be held by priests as Bunson explains:

The temple police units were normally composed of priests who were charged with maintaining the sanctity of the temple complexes. The regulations concerning sex, behavior, and attitude during and before all ritual ceremonies demanded a certain vigilance and the temples kept their own people available to ensure a harmonious spirit. (207)

The temple police would have been kept especially busy during religious festivals, many of which (such as that of Bastet or Hathor) encouraged drinking to excess and letting go of one's inhibitions.

The New Kingdom also saw the reformation and expansion of the military. Egypt's experience with the Hyksos had shown them how easily a foreign power could dominate their country, and they were not interested in experiencing that a second time. Ahmose I had first conceived the idea of buffer zones around Egypt's borders to keep the country secure, but this idea was taken further by his son and successor Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE).

The army Ahmose I led against the Hyksos was made up of Egyptian regulars, conscripts, and foreign mercenaries like the Medjay. Amenhotep I trained an Egyptian army of professionals and led them into Nubia to complete his father's campaigns and regain the lands lost during the 13th Dynasty. His successors continued the expansion of Egypt's borders but none more than Tuthmosis III (1458-1425 BCE), who established the Egyptian Empire conquering lands from Syria to Libya and down through Nubia.

By the time of Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE), Egypt was a vast empire with diplomatic and trade agreements with other great nations such as the Hittites, Mitanni, the Assyrian Empire, and the Kingdom of Babylon. Amenhotep III ruled over so vast and secure a country that he was able to occupy himself primarily with building monuments. He built so many in fact that early Egyptologists credited him with an exceptionally long reign.

His son would largely undo all the great accomplishments of the New Kingdom through religious reform which undercut the authority of the pharaoh, destroyed the economy, and soured relationships with other nations. Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE), perhaps in an attempt to neutralize the political power of the priests of Amun, banned all religious cults in the country except that of his personal god Aten. He closed the temples and moved the capital from Thebes to a new city he built in the Amarna region called Akhetaten where he sequestered himself with his wife Nefertiti and his family and neglected affairs of state.

The position of the pharaoh was legitimized by his adherence to the will of the gods. The temples throughout Egypt were not just places of worship but factories, dispensaries, workshops, counseling centers, houses of healing, educational and cultural centers. In closing them down, Akhenaten brought the forward momentum of the New Kingdom to a halt while he commissioned new temples and shrines built according to his monotheistic belief in the one god Aten. His successor, Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE) reversed his policies, returned the capital to Thebes, and reopened the temples but did not live long enough to complete the process. This was accomplished by the pharaoh Horemheb (1320-1295 BCE) who tried to erase any evidence that Akhenaten had ever existed. Horemheb brought Egypt back some social standing with other nations, improved the economy, and rebuilt the temples that had been destroyed, but the country never reached the heights it had known under Amenhotep III.

The government of the New Kingdom began at Thebes, but Ramesses II moved it north to a new city he built on the site of ancient Avaris, Per Ramesses. Thebes continued as an important religious center primarily because of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak to which every pharaoh of the New Kingdom contributed. The reasons for Ramesses II's move are unclear but one of the results was that, with the capital of the government far away in Per Ramesses, the priests of Amun at Thebes were free to do as they pleased. These priests increased their power to the point where they rivaled the pharaoh and the New Kingdom ended when the high priests of Thebes ruled from that city while the last of the New Kingdom pharaohs struggled to maintain control from Per Ramesses.

Late Period of Ancient Egypt & Ptolemaic Period

Egypt was again divided as it now entered the Third Intermediate Period (1069-525 BCE). The government at Thebes claimed supremacy while recognizing the legitimacy of the rulers at Per Ramesses and intermarrying with them. The division of the government weakened Egypt which began to degenerate into civil wars during the Late Period (c. 664-332 BCE). At this time, the would-be rulers of Egypt fought each other using Greek mercenaries who, in time, lost interest in the fight and started their own communities in the Nile River Valley.

In 671 and 666 BCE the Assyrians invaded and took control of the country, and in 525 BCE the Persians invaded. Under Persian rule Egypt became a satrapy with the capital at Memphis and, like the Assyrians before them, Persians were placed in all positions of power. When Alexander the Great conquered Persia, he took Egypt in 331 BCE, had himself crowned pharaoh at Memphis, and placed his Macedonians in power.

After Alexander's death, his general Ptolemy (323-285 BCE) founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt which lasted from 323-30 BCE. The Ptolemies, like the Hyksos before them, greatly admired Egyptian culture and incorporated it into their rule. Ptolemy I tried to blend the cultures of Greece and Egypt together to create a harmonious, multinational country - and he succeeded - but it did not last long beyond the reign of Ptolemy V (204-181 BCE). Under Ptolemy V's reign, the country was again in rebellion and the central government was weak. The last Ptolemaic pharaoh of Egypt was Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE), and after her death the country was annexed by Rome.

Legacy

The monarchial theocracy of Egypt lasted over 3,000 years, creating and maintaining one of the world's greatest ancient cultures. Many of the devices, artifacts, and practices of the modern day originated in Egypt's more stable periods of the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms when there was a strong central government which provided the stability necessary for the creation of art and culture.

The Egyptians invented paper and colored ink, advanced the art of writing, were the first people to widely use cosmetics, invented the toothbrush, toothpaste, and breath mints, advanced medical knowledge and practices such as fixing broken bones and performing surgery, created water clocks and calendars (originating the 365-day calendar in use today), as well as perfecting the art of brewing beer, agricultural advances like the ox-drawn plough, and even the practice of wearing wigs.

The kings and later pharaohs of ancient Egypt began their reigns by offering themselves to the service of the goddess of truth, Ma'at, who personified universal harmony and balance and embodied the concept of ma'at which was so important to Egyptian culture. By maintaining harmony, the king of Egypt provided the people with a culture that encouraged creativity and innovation. Each king would begin his reign by 'presenting Ma'at' to the other gods of the Egyptian pantheon as a way of assuring them that he would follow her precepts and encourage his people to do likewise during his reign. The government of ancient Egypt, for the most part, kept to this divine bargain with their gods and the result was the grand civilization of ancient Egypt.