Medical practice in ancient Egypt was so advanced that many of their observations, policies, and commonplace procedures would not be surpassed in the west for centuries after the fall of Rome and their practices would inform both Greek and Roman medicine. They understood that disease could be treated by pharmaceuticals, recognized the healing potential in massage and aromas, had male and female doctors who specialized in certain specific areas, and understood the importance of cleanliness in treating patients.

In the modern day it is recognized that disease and infection can be caused by germs and one might think people have always believed so but this is a relatively late innovation in human understanding. It was not until the 19th century CE that the germ theory of disease was confirmed by Louis Pasteur and proven by the work of British surgeon Joseph Lister.

Before either of them, the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865 CE) offered the then outlandish proposal to the medical community that they could cut mortality rates in their practices simply by washing their hands. He was mocked by doctors, who saw no reason to wash their hands before even the most invasive surgical procedures, and grew increasingly frustrated and bitter. Semmelweis was committed to a mental institution in 1865 CE where he died, after being severely beaten by guards, for suggesting a practice recognized as common sense today.

The ancient Egyptians would have accepted Semmelweis' proposal without hesitation; not because they understood the concept of germs, but because they valued cleanliness. The mortality rate following medical procedures in ancient Egypt was probably less than that of any European hospital in the Christian era until the mid-20th century CE when personal cleanliness and the sterilization of instruments became common practice.

Egyptologist Barbara Watterson notes that "medicine in ancient Egypt was relatively advanced and Egyptian doctors, who were all, with one or two exceptions, male, were skilled (46). Even so, for a civilization which regularly dissected the dead for embalming, doctors had little understanding of how most of the internal organs worked and blamed disease on supernatural forces.

Injury & Disease

Injuries were easy to understand in ancient Egypt; disease was a bit more difficult. When someone was injured there was a plain cause and an effect which could then be treated; when a person was sick, however, the cause was less clear and so diagnosis more problematic.

The cause of disease was usually understood as the consequence of sin and, when that seemed not the case, that the patient was under a demonic attack, was being plagued by an angry ghost, or that some god felt they needed to learn a lesson. Disease, therefore, was commonly treated through recitation by a doctor of magical spells. Watterson notes, "the earliest 'doctor' was a magician, for the Egyptians believed that disease and sickness were caused by an evil force entering the body" (65).

The types of diseases Egyptians suffered from were as numerous and varied as they are in the present day and included bilharsiasis (a disease contracted and spread through contaminated water); trachoma (an infection of the eye); malaria; dysentery; smallpox; pneumonia; cancer; heart disease; dementia; typhoid; arthritis; high blood pressure; bronchitis; tuberculosis; appendicitis; kidney stones; liver disease; curvature of the spine; the common cold, and ovarian cysts.

Besides magical spells, ancient Egyptians used incantations, amulets, offerings, aromas, tattoos, and statuary to either drive away the ghost or demon, placate the god or gods who had sent the illness, or invoke protection from a higher power as a preventative. The spells and incantations were written down on papyrus scrolls which became the medical texts of the day.

The Medical Texts

Although there were no doubt many more texts available in ancient Egypt, only a few have survived to the present. These few, however, provide a wealth of information on how the Egyptians saw disease and what they believed would alleviate a patient's symptoms or lead to a cure. They are named for the individual who owned them or the institution which houses them. All of them, to greater or lesser degrees, rely on sympathetic magic as well as practical technique.

The Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus, dated c. 1200 BCE, prescribes treatment for anorectal disease (problems associated with the anus and rectum) and prescribes cannabis for cancer patients (pre-dating the mention of cannabis in Herodotus, long thought to be the earliest mention of the drug). The Berlin Medical Papyrus (also known as the Brugsch Papyrus, dated to the New Kingdom, c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) deals with contraception, fertility, and includes the earliest known pregnancy tests. The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) treats cancer (for which, it says, there is no treatment), heart disease, diabetes, birth control, and depression. The Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE) is the oldest work on surgical techniques. The Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden (c. 3rd century CE) is devoted entirely to magical spells and divination. The Hearst Medical Papyrus (dated to the New Kingdom) treats urinary tract infections and digestive problems. The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE) deals with conception and pregnancy issues as well as contraception. The London Medical Papyrus (c. 1782-1570 BCE) offers prescriptions for issues related to the eyes, skin, burns, and pregnancy. These are only the papyrii recognized as focusing entirely on medicine. There are many more which touch on the subject but are not generally accepted as medical texts.

All of these works, at one time or another, were consulted by practicing doctors who routinely made house calls. The Egyptians called the science of medicine the "necessary art" for obvious reasons. Doctors were considered priests of the Per-Ankh, the House of Life, a kind of library/school attached to a temple, but the concept of the 'house of life' was also considered the healing knowledge of the individual doctors.

Doctors, Midwives, Nurses, & Dentists

Physicians in ancient Egypt could be male or female. The "first physician", later deified as a god of medicine and healing, was the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) best known for designing the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara. Imhotep is also remembered for initiating "secular medicine" through his treatises arguing that disease occurred naturally and was not a punishment from the gods. Women in the medical profession in Egypt go back to the Early Dynastic Period when Merit-Ptah was the royal court's chief physician c. 2700 BCE. Merit-Ptah is the first female doctor known by name in world history but evidence suggests a medical school at the Temple of Neith in Sais in Lower Egypt run by a woman whose name is unknown c. 3000 BCE.

Pesehet (c. 2500 BCE), another female physician often cited as the first, was the "Lady Overseer of Female Physicians", possibly associated with the school at Sais, attesting to the presence of women in medical practice at this time. The famous legend of Agnodice of Athens (c. 4th century BCE) relates how, denied entrance to the medical profession because she was a woman, she went to Egypt where women were respected in the field. How and where doctors received their training is not known although it has been established there was an important school in Alexandria as well as the one at Sais.

A doctor not only needed to be literate but also pure in body and spirit. Doctors were referred to as wabau, ritually pure, and were expected to bathe as frequently and carefully as a high priest. Each doctor had his or her speciality but there were also swnw, general practitioners, and sau, whose speciality was in the use of magic. Midwives, masseurs, nurses, attendants, and seers also assisted the doctor. Doctors are not thought to have had anything to do with births, however, which were handled entirely by midwives and the women of the house. Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown writes:

Midwifery appears to have been a solely female profession in ancient Egypt. That this was so is suggested by medical texts, which include gynaecological information, but do not discuss obstetrics. Additionally, men are never shown in birthing scenes, and in the Papyrus Westcar, the mother is assisted in birth by four goddesses. (82)

There is no evidence for medical training of midwives. In the Old Kingdom the word for 'midwife' is associated with the word for 'nurse', one who assisted a doctor, but this association ends after that period. Midwives could be female relatives, friends, or neighbors and do not seem to have been regarded as medical professionals.

The nurse could be female or male and was a highly respected medical professional although, as with midwives, there is no evidence of a school or professional training. The most essential kind of nurse was the wet nurse. Graves-Brown notes, "with the probable likelihood of high mortality of mothers, wet nurses would have been particularly important" (83). Women regularly died in childbirth and legal documents show agreements between wet nurses and families to care for the newborn in the event of the mother's death. The dry nurse, who would assist in procedures, was accorded such respect that he or she was represented during the time of the New Kingdom as linked with the divine. The association of the nurse with the doctor seems well established but not so much their link with the dentist.

Dentistry grew out of the established medical profession but never developed as widely. The ancient Egyptians suffered from dental problems throughout the entire history of the civilization so why dentists were not more plentiful, or better documented, is unclear. Doctors also practiced dentistry but there were dentists as far back as the Early Dynastic Period. The first dentist known by name in the world, in fact, is Hesyre (c. 2600 BCE), Chief of Dentists and Physician to the King under the reign of Djoser (c. 2700 BCE). Dental problems were especially prevalent owing to the Egyptian diet of coarse bread and their inability to keep sand out of their food. Egyptologist and historian Margaret Bunson writes:

Egyptians of all eras had terrible teeth and peridontal problems. By the New Kingdom, however, dental decay was critical. Physicians packed some teeth with honey and herbs, perhaps to stem infection or to ease pain. Some mummies were also provided with bridges and gold teeth. It is not known if these dental materials were used by the wearer while alive or inserted in the embalming process. (158)

Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) of the New Kingdom died from an abscessed tooth as did many others. Toothaches and dental problems were thought to be caused by a tooth-worm which needed to be driven out by magical spells and incantations. This belief no doubt originated in Mesopotamia, specifically Sumer, where incantations against the tooth-worm have been found in ancient cuneiform inscriptions.

Healing Gods, Medicines, & Implements

As with doctors, dentists used magical incantations to drive the tooth-worm from the patient and then applied what medicines they had to ease the pain. Doctors and dentists frequently used herbs and spices medicinally. A cure for chronic bad breath, for example, was chewing a gum ball of honey, cinnamon, myrrh, frankincense, and pignon. There is evidence of tooth extraction and false teeth with opium used as an anaesthetic. The importance of diet was recognized and changes in one's diet for improved health were suggested. Practical, hands-on, remedies were always applied first in cases of obvious physical injury but with toothaches or gum disease, as with any disease, a supernatural cause was assumed.

A belief in magic was deeply ingrained in the Egyptian culture and was considered as natural and normal as any other aspect of existence. The god of magic was also a god of medicine, Heka, who carried a staff entwined with two serpents. This symbol was passed on to the Greeks who associated it with their god of healing, Asclepius, and which is recognizable today as the caduceus of the medical profession. Although the caduceus no doubt traveled from Egypt to Greece it originated in Sumer as the staff of Ninazu, son of the Sumerian goddess of healing Gula.

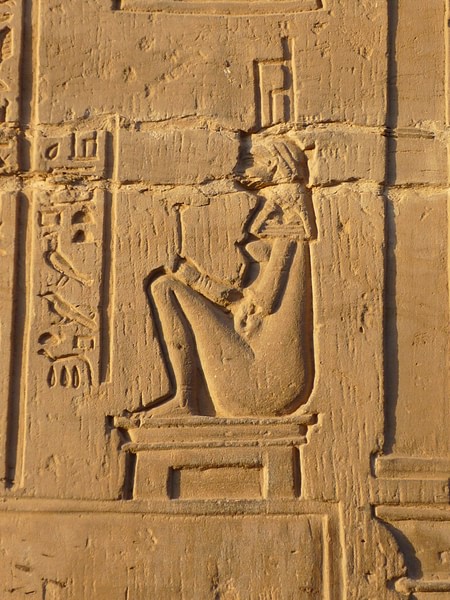

Besides Heka, there were a number of other important healing deities such as Sekhmet, Serket (also known as Selket), Sobek, and Nefertum. The priests of Serket were all doctors, though not every doctor was a member of her cult. Serket and Sekhmet were regularly invoked in magical spells and incantations along with Heka and, in certain cases, other deities such as Bes or Tawawret (usually dealing with fertility/children's diseases). Sobek, the crocodile god, seems to have been largely invoked for surgeries and invasive procedures. Nefertum, the god of perfumes associated with the lotus and healing, was invoked in procedures which today would be recognized as aromatherapy. In the Kahun Papyrus a course regularly prescribed for women is to fumigate them with incense to drive out an evil spirit and Nefertum would have been called upon in these instances.

Along with spells and incantations, the Egyptian doctors used naturally occurring herbs and spices as well as their own creations. Bunson writes:

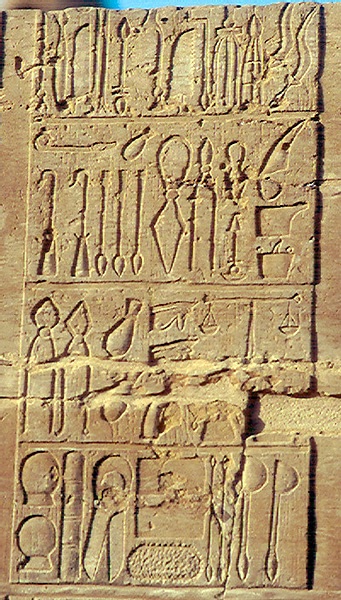

The pharmaceuticals of the ancient Egyptian priest-physicians included antacids, copper salts, turpentine, alum, astringents, alkaline laxatives, diuretics, sedatives, antispasmodics, calcium carbonates, and magnesia. They also employed many exotic herbs. All dispensing of medicines carefully stipulated in the medical papyri, with explicit instructions as to the exact dosage, the manner in which the medicine was to be taken internally (as with wine or food), and external applications. (158)

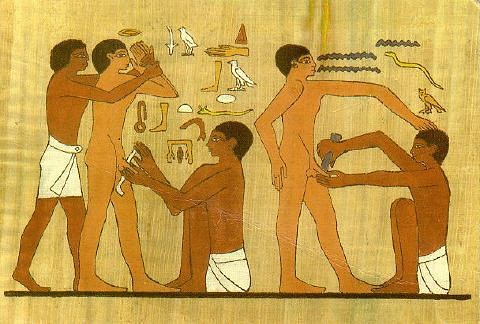

Surgical procedures were common and many instruments have been identified which are still in use today. The Egyptians had a flint and a metal scalpel, dental pliers, a bone saw, probes, the catheter, clamps for stopping blood flow, specula, forceps, lancets for opening veins, sponges, scissors, phials, bandages of linen, and scales for weighing the proper amount of raw materials to mix for medicines. Surgeries were frequently successful as evidenced by mummies and other remains found who survived amputations and even brain surgery for years. Prosthetic limbs, made usually of wood, have also been found.

Conclusion

Not all of the medical practices in Egypt were so successful, however. Circumcision was a religious ritual performed on boys between the ages of 10 and 14 marking the transition from adolescence to manhood. It was performed by a doctor who also served as a temple priest, using a flint blade and reciting incantations, but in spite of their precautions this procedure still sometimes resulted in infection. Since the nature of the infection was unknown to them, it was considered the result of a supernatural influence and dealt with through magic spells; this most likely resulted in the deaths of many young men.

Because of their belief in the womb as connected to all parts of a woman's body, fumigation of the womb was a common prescription, accompanied by incantations, which would miss the actual cause of the problem. Eye problems were treated with a dose of bat's blood because it was thought the night-vision of the bat would be transferred to the patient; no evidence suggests this was effective.

Although the embalmers of Egypt no doubt came to understand how the organs they removed from the body worked with each other, this knowledge was never shared with doctors. These two professions moved in completely different spheres and what each did within their own job description was not considered relevant to the other. It is for this reason that, even though the Egyptians had the means of exploring internal medicine, they never did.

The heart, though recognized as a pump, was also thought to be the center of emotion, personality, and intellect; the heart was preserved in the deceased while the brain was scraped out and discarded as worthless. Although they recognized liver disease they had no understanding of the function of the liver and while regularly dealing with miscarriages and infertility, had no understanding of obstetrics. The culture's reliance on supernatural assistance from the gods prevented them from exploring more immediate and practical solutions to the medical problems they encountered daily.

Still, the Egyptian physician was widely respected for their skill and knowledge and was called upon by the kings and nobility of other nations. The Greeks especially admired the Egyptian medical profession and adopted a number of their beliefs and techniques. Later famous physicians of Rome and Greece - like Galen and Hippocrates ("father of modern medicine") - studied the Egyptian texts and symbols and so passed down the traditions to the present day.