Papyrus is a plant (cyperus papyrus) which once grew in abundance, primarily in the wilds of the Egyptian Delta but also elsewhere in the Nile River Valley, but is now quite rare. Papyrus buds opened from a horizontal root growing in shallow fresh water and the deeply saturated Delta mud. Stalks reached up to 16 feet tall (5 m) ending in small brown flowers which often bore fruit. These plants once were simply part of the natural vegetation of the region, but once people found a utilitarian purpose for them, they were cultivated and managed in farms, harvested heavily, and their supply depleted. Papyrus still exists in Egypt today but in greatly reduced number.

The papyrus of Egypt is most closely associated with writing - in fact, the English word 'paper' comes from the word 'papyrus' - but the Egyptians found many uses for the plant other than a writing surface for documents and texts. Papyrus was used as a food source, to make rope, for sandals, for boxes and baskets and mats, as window shades, material for toys such as dolls, as amulets to ward off throat diseases, and even to make small fishing boats. It also played a part in religious devotion as it was often bound together to form the symbol of the ankh and offered to the gods as a gift. Papyrus also served as a political symbol through its use in the Sma-Tawy, the insignia of the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt. This symbol is a bouquet of papyrus (associated with the Delta of Lower Egypt) bound with a lotus (the symbol of Upper Egypt).

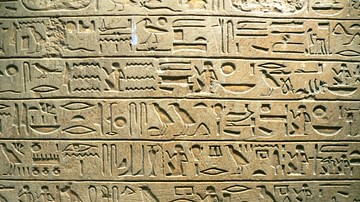

The plant may also be seen etched in stone on temples and monuments, symbolizing life and eternity as the Egyptian afterlife, known as the Field of Reeds, was thought to mirror the fertile Nile River Valley right down to the abundance of papyrus. The name 'Field of Reeds' actually refers to the reeds of the papyrus plant. At the same time, however, the papyrus thicket represented the unknown and the forces of chaos. Kings are regularly depicted hunting in the papyrus fields of the Delta to symbolize the imposition of order over chaos.

The dark and mysterious nature of the papyrus fields were frequently employed as a motif in mythology. Papyrus fields feature in a number of important myths; most notably that of Osiris and Isis after Osiris is murdered by his brother Set and Isis hides their child Horus in the marshes of the Delta. The papyrus reeds, in this case, hid the mother and child from Set's intentions to kill Horus and so again symbolize order prevailing over disorder and light over darkness.

Name & Processing

Papyrus is the Greek name for the plant and may come from the Egyptian word papuro (also given as pa-per-aa) meaning 'the royal' or 'that of the pharaoh' because the central government had control of papyrus processing as they owned the land and, later, oversaw the farms the plant grew on. The ancient Egyptians called the plant djet or tjufi or wadj, forms of the concept of freshness. Wadj further denotes lushness, flourishing, greenness. Once papyrus was cut, harvested, and processed into rolls, it was called djema which may mean 'clean' or 'open' in reference to the fresh writing surface.

Papyrus was harvested from the beginning of the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-c.3150 BCE) and continued to be throughout Egypt's history down to the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) and into Roman Egypt (30 BCE - c. 640 CE). Field workers would harvest the plants from the marsh by cutting them at the bottom with sharp blades, bundling the stalks together, and carrying them to some conveyance which brought them to a processing center. Historian Margaret Bunson describes the process whereby the plants were made into workable sheets:

The stem of the papyrus plant was cut into thin strips which were laid side by side in perpendicular fashion. A solution of resin from the plant was laid down and a second layer of papyrus was put into place, horizontally. The two layers were then pressed and allowed to dry. Immense rolls of papyrus could be made by joining the single sheets...The sides of a papyrus where the fibers run horizontally are the recto and, where the fibers run vertically, the verso. The recto was preferred but the verso was used for documents as well, allowing two separate texts to be included on a single papyrus. (201)

Egyptologist Rosalie David adds to the description, detailing the stages of this process of forming the plants into sheets:

In the first stage, the stalk of the plant was sliced into pieces and the pith was cut out and beaten with a hammer to produce wafers. These were arranged side by side and crosswise in two layers and were then beaten into sheets. Then the individual pages were stuck together in the same way to form a standard roll of twenty pages; sometimes the rolls were stuck together as required to provide an even longer writing surface. After drying in the sun the full strip was rolled up with the horizontal fibers on the inside. This was the "recto" that would be written on first. (200)

The sheets, now joined into rolls, were then transported to temples, government buildings, the market or exported in trade. Although papyrus is closely associated with writing in general, it was actually mostly used only for religious and government texts because manufacturing costs were fairly expensive. Not only was the manual labor in the fields and marshes costly, it took skilled workers to methodically beat and process the plant without destroying it. All of the extant papyri are from temples, government offices, or personal collections of wealthy or at least well-off individuals. Written works often appear on pieces of wood, stone, or ostraca (shards from clay pots). The image of the Egyptian scribe hunched over his papyrus scroll is accurate, but long before he got his hands on that scroll, he would have spent literally years practicing writing on potsherds, chunks of stone, and pieces of wood.

Uses & Examples

The scribes of ancient Egypt spent years learning their craft and, even if they were from wealthy families, they still were not allowed to waste precious material on their lessons. David notes that "the most common and cheapest writing materials were ostraca and pieces of wood. These were often used by schoolboys for their letters and exercises" (200). Only once one had mastered the basics of writing was one allowed to practice on a papyrus scroll. David notes how exercises found practiced on ostraca are sometimes duplicated on papyrus, which often supplies missing words or phrases to works which are incomplete in either form.

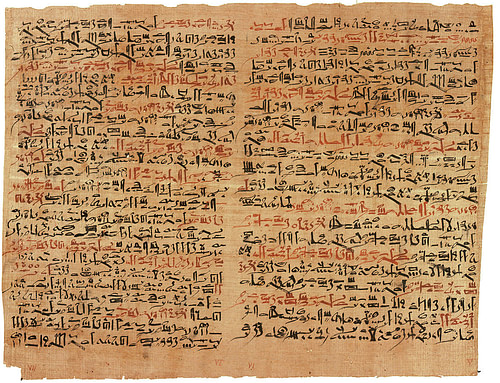

As a writing material, papyrus was used for hymns, religious texts, spiritual admonitions, letters, official documents, proclamations, love poems, medical texts, scientific or technical manuals, record-keeping, magical treatises, and literature. Extant scrolls range from fragments to one page to the famous Ebers Papyrus which is 110 pages long on a scroll sixty-five feet (20 metres) long. The Ebers Papyrus is a medical text which is routinely cited as evidence of how medicine and magic were interrelated in ancient Egypt. Along with other papyrus scrolls like the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus, the London Medical Papyrus, and the Edwin Smith Papyrus, to name only a few, these works attest to the vast medical knowledge and skill of the ancient Egyptians and how they went about addressing major and minor injuries, various ailments, and serious conditions such as cancer and heart disease. Cases of anxiety, depression, and trauma are also dealt with in the medical texts of Egypt as are subjects like abortion, birth control, menstrual cramps, and infertility.

Papyrus was also, of course, used for literary texts. The term 'literature' is commonly applied to an array of ancient Egyptian works from medical texts, royal decrees and proclamations, letters, autobiographies and biographies, religious texts, and others besides works of the imagination. A number of these works were inscribed in tombs, on temple walls, or on stele and obelisks while those which fit the common definition of 'literature' were written on papyrus. Some of the best known are The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, The Report of Wenamun, and The Tale of Sinuhe, but there are many others.

Ancient Egyptian scribes wrote in black and red ink. Red was used for the names of demons or evil spirits, to mark the beginning of a new paragraph, for emphasis of a word or passage, and for punctuation in some cases. Scribes carried a wooden case which held cakes of black and red paint and a water flask to mix and dilute the paint into ink. The pen was initially a thin reed with a soft tip but was replaced in the third century BCE by the stylus, a more robust reed sharpened to a very fine point. A scribe would begin a work on the recto of the papyrus roll, write until it was filled, and then flip it over to continue the text on the verso. In some instances, a papyrus roll on which only the recto had been used would be taken by another scribe and used for another work, either complementary or completely unrelated.

As noted, however, papyrus was not used exclusively for writing. The plant could be baked and eaten, and Herodotus reports that the papyrus root was a staple of the Egyptian diet. It was cut and prepared in a variety of dishes much as the later potato came to be in other cultures. Papyrus was not only a food source but leaned itself to an incredibly diverse range of uses. The earliest Egyptian skiffs were made by tightly weaving stalks of papyrus and binding them with rope, also made of papyrus. This technique created a light-weight water-tight boat which could easily be carried by hunters or fishermen. The papyrus skiff is featured in numerous tomb and temple paintings and has a markedly different, more linear, shape than later wooden boats built on the same design. Papyrus continued to be a significant aspect of the Egyptian boat even after wood replaced it as the primary material. When small wooden vessels were developed into large sailing ships, the plant was woven into ropes for the sails. Papyrus rope, however, was used for a number of purposes besides sailing and papyrus fiber, which was quite strong, proved useful in other products.

Mats and window shades were woven through a technique similar to that used to make writing material. The shafts of the plant were set down vertically and then woven with others horizontally and pulled tightly; they were then bound with a thinner fiber from the plant. Sandals were made by coiling the papyrus and were so sturdy that many examples of them have been found thousands of years after they were made still in good condition. Papyrus sandals required a great deal of skill to make and were too expensive for most people. Herodotus reports that the priests of Amun only wore papyrus sandals which, along with other evidence, scholars interpret as further proof of the priests' great wealth. Dolls or other toy figures were made by bunching up the stalks and then shaping them through tightly tied fibers to create a head, arms, and legs.

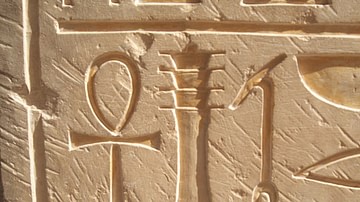

This "bunching" of the plant was employed in the creation of a popular offering to the gods: the shape of the ankh. The ankh, symbol of life and promise of life everlasting, was one of the most important icons of ancient Egypt and frequently placed with offering to the gods at temples or obelisks. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson notes how "the ankh could be symbolized by floral bouquets and the 'papyrus swathe' (bundles of flowers and plant foliage tied around a central bunch of papyrus stalks) which was commonly offered to the gods" (161). This same technique was used in creating the Sma-Tawy symbol representing the unity of the country. The association of papyrus with unity and the gods is fitting in that the plant, like the gods and the gifts of the land, was an integral part of the people's lives.