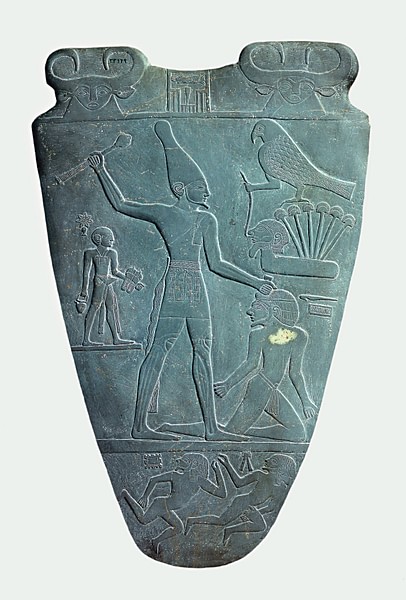

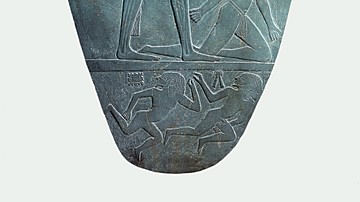

The Narmer Palette, an ancient Egyptian ceremonial engraving, depicts the great king Narmer (c. 3150 BCE) conquering his enemies with the support and approval of his gods. This piece, dating from c. 3200-3000 BCE, was initially thought to be an accurate historical depiction of the unification of Egypt under Narmer, the first king of the First Dynasty of Egypt.

Recent revisions in scholarship, however, now interpret the artifact as a symbolic rendering of this historical event and claim that Narmer (also known as Menes) may or may not have united the country by force but that the concept of the king as a mighty warrior was an important cultural value and so Narmer was depicted as a conqueror.

The great kings of Mesopotamia, especially the Assyrian rulers, left behind many inscriptions of their military victories, prisoners taken, cities destroyed but for most of Egypt's early history such records do not exist. The Egyptians considered their land the most perfect in the world and were not so much interested in conquest as in preservation of what they had. The early records of Egyptian warfare all have to do with civil unrest, not conquest of other lands, and this would be the paradigm from the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150-2613 BCE) until the time of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) when the kings of the 12th Dynasty maintained a standing army which they led on military campaigns beyond their borders.

The Development of Professional Warfare

Although modern-day scholars disagree on whether Narmer united Egypt through conquest, there is no doubt that a military force under a strong leader was necessary to hold the country together. Throughout the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt, there is evidence of unrest, perhaps even a division of the country at one point, and civil wars between factions fighting for the throne.

Through the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) the central government relied on regional governors (nomarchs) to supply men for the army. The nomarch would conscript soldiers in their region and send them to the king. Each battalion carried standards bearing the totem of their district (nome) and their loyalties were with their community, their brothers-in-arms, and to their nomarch. The effectiveness of this early militia is attested to by the successful campaigns in Nubia, Syria, and Palestine of Old Kingdom monarchs to either secure the borders, quell uprisings, or seize resources for the crown. The soldiers fought for the king and their country but they were not a united Egyptian army so much as a band of smaller military units fighting for a common goal. The conscripts were often supplemented by Nubian mercenaries who had the same degree of loyalty to the king as long as they were being paid.

The rise in the power of individual nomarchs was among the contributing factors in the collapse of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 2181-2040 BCE). The central government at Memphis was no longer relevant as each district's nomarch assumed control of their own region, built temples in their own honor instead of a king's, and used their militia for their own ends. In an attempt to regain some of their lost prestige, perhaps, the kings at Memphis moved their capital to the city of Herakleopolis, which was more centrally located. They were no more effective at the new location, however, than they had been at the old and were overthrown by Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) of Thebes who initiated the period of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

It is likely that Mentuhotep II led an army of conscripts from Thebes but he may have already mobilized a professional fighting force in his district. It is also entirely possible that there was a core of professional soldiers who fought for the king as far back as the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-3150 BCE) but the evidence for this is unclear. Most scholars agree that it was Mentuhotep II's successor, Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) who created the first standing army in Egypt. This would make a great deal of sense because it would have taken power from the individual nomarchs and placed it in the hands of the king. The king now had direct control of an army which was loyal to him and the country as a whole, not to different nomarchs and their regions.

Armies & Weapons in the Old Kingdom

The weapons of the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods were primarily maces, daggers, and spears. By the time of the Old Kingdom the bow and arrow, among other weaponry, had been added as historian Margaret Bunson explains:

The soldiers of the Old Kingdom were depicted as wearing skull caps and carrying clan or nome-totems. They used maces with wooden heads or pear-shaped stone heads. Bows and arrows were standard gear, with square-tipped flint arrowheads and leather quivers. Some shields, made of hides, were in use but not generally. Most of the troops were barefoot, dressed in simple kilts, or naked. (168)

The Egyptians used a simple single-arched bow which was hard to draw, had a short range, and unreliable accuracy. The soldiers were all from the lower-class peasantry population and had little training. It is unlikely, though possible, that they would have had experience with a bow in hunting. The peasantry owned no land in Egypt and hunting was prohibited without the consent of the upper-class landowner. Further, the Egyptian diet was mostly vegetarian and hunting was a sport of royalty. Still, with archers firing en masse from a close position, these weapons could be very effective. After a volley or two of arrows, the soldiers would close with their opponents using hand weapons. The Egyptian navy at this time was used only to transport troops, not for enemy engagement.

Middle Kingdom Warfare

By the time of the Middle Kingdom the troops carried copper axes and swords. The long, bronze spear became standard as did body armor of leather over short kilts. The army was better organized with "a minister of war and a commander in chief of the army, or an official who worked in that capacity" (Bunson, 169). These professional troops were highly trained and there were elite "shock troops" used as the vanguard. Officers were in charge of an unspecified number of men in their units and reported to a commander who then reported up the chain of command; it is unclear exactly what the individual responsibilities were or what they were known as but military life offered a much greater opportunity at this time than in the past. Historian Marc van de Mieroop writes:

Although our knowledge of the military in the Middle Kingdom is very limited, it seems that its role in society was much greater than in the Old Kingdom. The army was well organized and in the 12th dynasty it had a core of professional soldiers. They served for prolonged periods of time and were regularly stationed abroad. The army provided an outlet for ambitious men to make careers. The bulk of the troops continued to be recruited from the populations of the provinces and participated in individual campaigns only. How many troops were involved and how long they served remains unknown. (112)

The military of the Middle Kingdom reached its apex under the reign of the warrior-king Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) who was the model for the later legendary conqueror Sesostris made famous by Greek writers. Senusret III led his men on major campaigns in Nubia and Palestine, abolished the position of nomarch and took more direct control of the regions his soldiers came from, and secured Egypt's borders with manned fortifications.

The Contributions of the Hyksos

The kings of the 12th Dynasty, like Senusret III, were strong rulers who contributed a great deal to Egyptian stability but the 13th Dynasty was weaker and failed to maintain an effective central government. The Hyksos, a Semitic people who immigrated from Syria-Palestine, settled in Lower Egypt at Avaris and, in time, had amassed enough wealth to wield political power. The rise of the Hyksos marks the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period in Egypt (c. 1782-1570 BCE) when the country was divided between the Hyksos in the north, the Egyptians in the middle, and the Nubians to the south. This situation continued, with the three engaged in trade and uneasy peace, until the Egyptian king at Thebes, Seqenenra Taa (c. 1580 BCE), felt challenged by Apepi, the Hyksos king at Avaris, and attacked. The Hyksos were finally driven out of Egypt by Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) of Thebes and this event marks the beginning of the New Kingdom of Egypt.

The Egyptian army during the Second Intermediate Period was largely made up of Medjay, Nubian warriors who fought as mercenaries. Medjay served as scouts, light infantry, and finally as cavalry units. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos, the horse was unknown in Egypt and so, of course, was the chariot. Although later Egyptian and Greek writers characterized the time of the Hyksos as a dark age of chaos and destruction, the foreign kings introduced a number of significant innovations to the culture, especially concerning warfare and weaponry. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson notes:

The Hyksos, being from western Asia, brought the Egyptians into contact with the peoples and the culture of that region as never before and introduced them to the horse-drawn war chariot; to a composite bow made from wood reinforced with strips of sinew and horn, a more elastic weapon with a greater range than their own simple bow; to a schimitar-shaped sword, called the Khopesh, and to a bronze dagger with a narrow blade cast in one piece with the tang. The Egyptians developed this weapon into a short sword. (60)

Egypt had never been invaded and occupied by a foreign power before and the rulers of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) wanted to make sure it never would be again. The early kings of this period, therefore, placed particular emphasis on expanding the borders of the country to create buffer zones and, in doing so, launched the Egyptian Empire.

The Army of the Empire

The period of the New Kingdom is the best known by modern-day audiences with some of the most famous rulers (Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Seti I, Ramesses II). It was the period when Egypt reached its height in prestige, power, and wealth. Van de Mieroop writes:

New Kingdom Egypt was an imperialist state: the country annexed territories outside its traditional borders and controlled them for its own benefit. This policy had its roots in earlier periods, when military conquest was a regular part of royal duties, but peaked in the New Kingdom when Egypt was in an almost permanent state of war. (157)

The empire of the New Kingdom starts with Ahmose I's pursuit of the Hyksos out of Egypt, through Palestine, and into Syria but really begins with the reign of Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE) who expanded the southern borders into Nubia. Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) went further and campaigned through Palestine and Syria into Mesopotamia, reaching the Euphrates River. Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) sent expeditions to Nubia and Syria and organized a trade mission to Punt which included a military escort. Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE), however, is considered the greatest warrior king of the early New Kingdom, conquering Libya, expanding into Nubia, and securing regions throughout the Levant. Thutmose III, leading at least 17 different campaigns in 20 years, established the Egyptian Empire at its height and, to do this, required a professional army. Bunson writes:

The army was no longer a confederation of nome levies but a first-class military force. The king was the commander in chief but the vizier and another administrative series of units handled the logistical and reserve affairs...The army was organized into divisions, both chariot and infantry. Each division numbered approximately 5,000 men. These divisions carried the names of the principal deities of the nation. (170)

Under this new organization, the chain of command in a division, from the lowest to highest rung, was strictly hierarchical. In each division, there was an officer in charge of 50 soldiers who reported to a superior officer in charge of 250 men. This officer, in turn, reported to a captain who was responsible to a troop commander. Above the troop commander was the troop overseer, a military official in charge of a garrison, who reported to the fortification overseer, a higher official in charge of the forts where the division was stationed, who reported to a lieutenant commander. The lieutenant commander reported to the general who was responsible to the Egyptian vizier and the pharaoh.

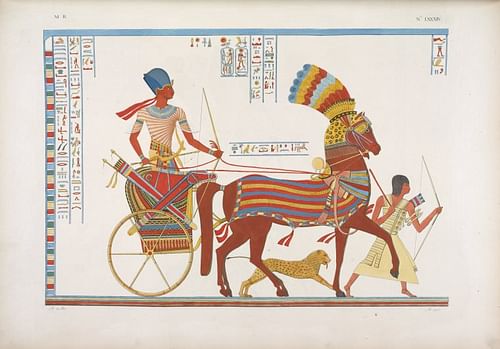

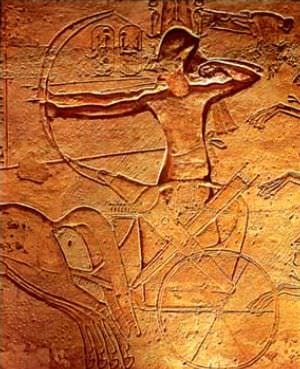

An important aspect of this new army was the horse-drawn chariot introduced by the Hyksos. Van de Mieroop notes how, "Charioteers were trained fighters and also men of wealth, who provided their own equipment. They received greater rewards than other soldiers and had a high social status" (158). The Egyptians modified the chariot of the Hyksos to make it lighter, more maneuverable, and faster. Each chariot held two men, a driver, and a warrior. They wore scale armor on the upper body and a light kilt below. The driver was a highly trained charioteer who controlled the vehicle while the warrior, armed with a bow, arrows, and a spear, engaged the enemy. Chariot forces were divided into squadrons of 12 chariots and 24 men with a thirteenth as squadron commander.

It was this army which expanded Egypt into an empire and allowed for the opulent reigns of pharaohs such as Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) under whose rule Egypt enjoyed unprecedented peace and prosperity. This is not to say there were no conflicts during his reign but the army kept such unpleasantness far from the borders of the country. This is also the army, under Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE), which engaged the Hittites in 1274 BCE at the famous Battle of Kadesh.

Ramesses II moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to a new city he built on the former site of Avaris in Lower Egypt, Per-Ramesses ("City of Ramesses"). As usual, this pharaoh spared no expense in lavishing his new capital with adornments and monuments, temples to the gods, and beautiful buildings but, as Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson explains, there was more going on at Per-Ramesses than architectural advancements and religious festivals:

While the court scribes and poets lauded Per-Ramesses as a great royal residence, filled with exuberance and joy, there was also a more menacing side to this most ambitious of royal projects. One of the largest buildings was a vast bronze-smelting factory whose hundreds of workers spent their days making armaments. State-of-the-art high-temperature furnaces were heated by blast pipes worked by bellows. As the molten metal came out, sweating laborers poured it into molds for shields and swords. In dirty, hot, and dangerous conditions, the pharaoh's people made the weapons for the pharaoh's army. Another large area of the city was given over to stables, exercise grounds, and repair works for the king's chariot corps...In short, Per-Ramesses was less pleasure dome and more military-industrial complex. (314)

Ramesses II launched his campaign against the Hittites at Kadesh from Per-Ramesses, riding in his chariot at the head of four divisions of 20,000 men. According to his inscriptions, the battle was an overwhelming Egyptian victory but his opponent, Muwatalli II of the Hittite Empire, claimed precisely the same for his side. Scholars today have concluded that the Battle of Kadesh was more of a draw than a victory for either side but Ramesses had details of his great victory inscribed and read throughout the country and the conflict would result in the world's first peace treaty signed between the Egyptian and Hittite Empires in 1258 BCE.

The Egyptian Navy

Besides the army and the chariotry, there was a third branch of the military, the navy. As noted, in the Old Kingdom the navy was used primarily to transport infantry. Even as late as the Second Intermediate Period, Kamose was using the navy simply as transport to bring his troops down the Nile for the sack of Avaris. In the New Kingdom, however, the navy became more prestigious as foreign invaders threatened Egypt's prosperity by sea.

The best documented, and most determined, of these invaders are known as the Sea Peoples, a mysterious group who have yet to be positively identified. They seem to have been a coalition of different ethnicities who harried the coasts of the Mediterranean between c. 1276-1178 BCE and they may have played a significant role in the Bronze Age Collapse. Ramesses II, his successor Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE) and Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) all fought off the Sea Peoples during their reigns.

Ramesses II, who had a very efficient intelligence network, learned of the coming invasion in time to place his navy along the coast at the mouth of the Nile. He then positioned a small fleet in a defensive position to draw the ships of the Sea Peoples into a trap. Once they were in position, he released his more numerous and larger ships from the sides and destroyed his opponent.

This engagement, like many others of the Egyptian navy, was fought at sea by land troops. Although the soldiers were trained to fight on water they were not seamen. The Egyptians were not a seafaring people and their navy gives evidence of this. The ships were often incredibly large with a crew of around 250 men. Smaller ships held a crew of 50 with 20 of these delegated to rowing, sailing, maneuvering the vessel and 30 assigned to combat. Although Ramesses II emphasized his victory in a sea battle, it was actually a land battle fought on water. The Egyptian ships closed with those of the Sea Peoples enabling boarding and then sinking of the enemy ships; the ships themselves did not do battle.

This same is true of Ramesses III's engagement with the Sea Peoples. He incorporated his predecessor's trick of luring the Sea Peoples into a trap and then relied on guerilla warfare to destroy them. Merenptah avoided a sea engagement entirely and met the enemy on land at Pi-yer where his New Kingdom army slaughtered over 6,000 enemy soldiers.

The true value of the Egyptian navy was intimidation of potential invaders and transport of land troops quickly. Thutmose III used the navy to good effect in a number of campaigns and former cargo ships were frequently conscripted and turned into naval vessels for campaigns up or down the Nile. The ships would be outfitted with bulwarks to protect the crew from incoming missiles and would sometimes also be improved for maneuverability.

Decline of the Egyptian Military

Ramesses III was the last effective pharaoh of the New Kingdom and, after he died, great military successes became more and more a thing of the past. The pharaohs who followed him were not strong enough to hold the empire and it began to fall apart. A contributing factor to this decline was actually Ramesses II's decision to build Per-Ramesses and move his capital there from Thebes. Thebes was the site of the great Temple of Amun at Karnak and the priests of Amun, not just there but throughout Egypt, were very powerful. When the capital moved to Per-Ramesses the priests at Thebes found they had a good deal more freedom to amass even more wealth and power than before. By the time of the reign of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE) the country was divided between his rule from Per-Ramesses and that of the priests of Amun at Thebes.

This division begins the era known as the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE). Whatever power Egypt had at sea was eclipsed by the Greek and Phoenician navies of the time which were much faster, better-equipped, and manned by experienced seafarers. Egypt entered the so-called Iron Age II in c. 1000 BCE when they began producing iron tools and weapons. Forging iron required charcoal from burned lumber, however, and Egypt had few trees. In 671 BCE the country was invaded by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon who, with his professional army wielding weapons of iron, massacred the Egyptian army, burned the city of Memphis, and brought royal captives back to Nineveh. In 666 BCE his son Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt and conquered the land all the way past Thebes. Again, the iron weapons, better armor, and tactics of the Assyrians proved superior to the Egyptian military.

The Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE) begins after the Assyrian invasions, which is marked by the dwindling power of Egyptian rulers and incessant warfare. The Egyptian royalty fought one another for supremacy using Greek mercenaries who would as easily fight for one side as another. Eventually many of these Greek soldiers stopped fighting entirely and just settled with families in Egypt.

The Egyptian military had acquired iron weapons by this time and developed a strong cavalry but these innovations were not enough to raise it to the level of efficiency and power it had before. Iron was very expensive because all the elements required had to be imported.

The Persians invaded in 525 BCE and defeated the Egyptian garrison at Pelusium but this had nothing to do with superior military might. The Persian general Cambyses II knew of the great veneration the Egyptians had for animals in general and cats in particular. He ordered his men to round up as many animals as possible and drive them before the army. Further, he had his soldiers paint the image of the goddess Bastet, among the most popular of all Egyptian deities, on their shields. He then marched on the city with the animals in front of him declaring that he would hurl cats over the walls if he did not receive an immediate surrender. The Egyptians, fearing for the safety of the animals (and also their own if they should offend Bastet), lay down their arms and surrendered. Afterwards, Cambyses II is said to have thrown cats from a sack into the faces of the Egyptians in contempt.

Alexander the Great took Egypt from the Persians in 331 BCE and, after his death, it came under the rule of his general Ptolemy who became Ptolemy I of Egypt (323-283 BCE). The Ptolemaic Dynasty were Macedonian-Greek rulers who employed the military tactics and weaponry of their own country. The history of ancient Egyptian warfare essentially ends with the New Kingdom. Whatever innovations and progress in weaponry were made after 1069 BCE no longer mattered on a large scale to the Egyptian military because there was no longer a strong central government to support it.