Einsatzgruppen ('deployment groups') were secret Nazi killing units, who systematically sought out and murdered civilians identified as enemies of the Third Reich. Operating without any legal restrictions in territories newly conquered by the regular German armed forces during the Second World War (1939-45), the Einsatzgruppen were responsible for over 2 million deaths.

The victims of the Einsatzgruppen included Jewish people, Romani people, intellectuals, local officials, communists, partisans, and anyone else considered enemies of the German Nazi state. Jewish people were a particular target as part of the Nazis' Final Solution. Victims were rounded up for immediate mass execution or internment in concentration camps. The activities of the Einsatzgruppen became clear during the post-war Nuremberg trials when both survivors and those directly involved in the units gave evidence.

The Final Solution

Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942) was the first head of the Reich Security Main Office or RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt), which included within it such terror organisations as the Nazi secret police (Gestapo), the criminal police (Kripo), and the military intelligence service of the Nazi Party, the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Section or SD). When Heydrich was assassinated by the Czech Resistance in May 1942, Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-1946) took over as the new permanent head of the RSHA. The leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), gave the RSHA three main roles: policing and repressing enemies of Nazism, gathering intelligence, and eliminating those people identified by the Nazis as being racially inferior. In none of these roles was the RSHA limited by any legal restrictions. Those identified as enemies of the Third Reich need not have been guilty of any specific crime, and they were given no legal representation or means of appeal. In other words, any civilian could be rounded up, imprisoned, and executed without any reason given whatsoever. Those who tried to defend the innocent were very often beaten, imprisoned, or executed themselves.

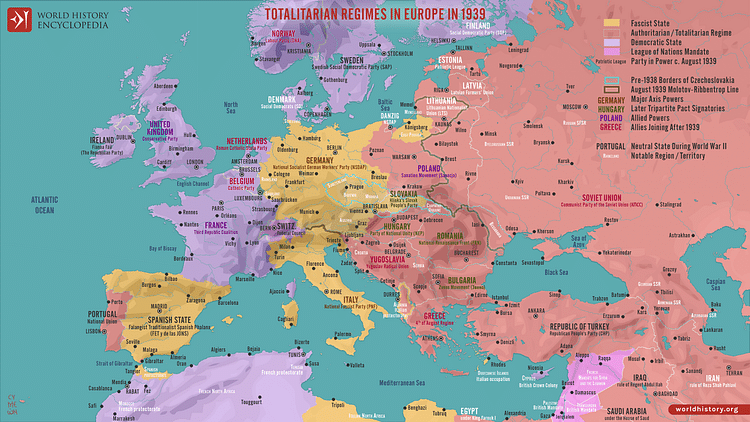

Heydrich and his chief lieutenant Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962) were assigned by Hitler many diabolical projects, which included the Final Solution, that is the extermination of all Jewish people (the Holocaust). Other 'undesirables' and, therefore, targets of the RSHA, included Romani people, freemasons, communists, those with physical or mental disabilities, and anyone who might resist the Third Reich, such as priests and intellectuals (including doctors, civil servants, and teachers). As the German army advanced into new territories, particularly on the Eastern Front, more and more "enemies of the state" had to be dealt with. Additional "enemies" now included prisoners of war, partisans, former members of local government, and anyone associated with the authority of the previous regime. To eliminate these "enemies", the RSHA was given the task of organising highly secret mobile killing squads, which operated behind the advancing regular German army and very often with its cooperation. These squads were the Einsatzgruppen.

The Killing Squads

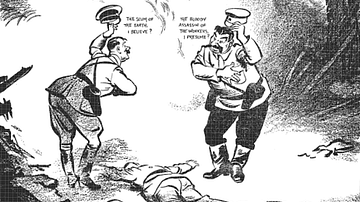

Operating in Austria after the Anschluss of March 1938, and again following Hitler's occupation of Czechoslovakia, the Einsatzgruppen project was greatly expanded during the invasion of Poland in 1939. Seven Einsatzgruppen units, each consisting of 400-600 SS or SD men, operated during this campaign, killing individuals on the spot, wiping out entire villages, and systematically rounding up people for transportation to ghettos. The victims were men, women, and children – the latter because men like Heydrich and Eichmann did not want to create a future generation of avengers for their parents' deaths. In Poland, "within a week of the invasion, SS commanders were boasting of killing 200 Polish citizens a day" (Cimino, 116). The numbers quickly escalated.

The Einsatzgruppen were so ruthless that many regular army officers tried to distance themselves from their operations. Nevertheless, the regular German army was involved in Einsatzgruppen activities and very often cooperated, as did local groups such as anti-communists and those who simply sought revenge on local figures of authority after the USSR's occupation.

When Hitler was hoping to invade England in 1940, six squads of Einsatzgruppen were slated to operate there. A Black Book was compiled containing a list of over 2,800 prominent people the Einsatzgruppen should arrest with priority once the invasion had got underway. The diverse names on the list include the prime minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965), the Czech prime minister in exile, Edvard Beneš (1884-1948), the feminist and pacifist Vera Brittain (1893-1970), and the author E. M. Forster (1879-1970). Everyone on the list had one thing in common: their views opposed those of the Nazis.

Expansion in the East

When the invasion of the USSR (Operation Barbarossa) began in June 1941, Einsatzgruppen were again deployed: five groups totalling 3,000 soldiers. Einsatzgruppen members continued to be recruited from the SS and from the SD. In former Soviet territory, the orders were to execute all Jewish people. "By November 1941, perhaps as many as 600,000 Jews had been liquidated" (Dear, 252). Those with links to the Communist Party were also hunted down.

Heydrich ordered the summary execution of all Soviet officials, members of the Comintern, 'extremist' Communist Party members, members of the central, provincial and district committees of the Communist Party, Red Army political commissars and all Communist Party members of Jewish origin.

(Cimino, 130-1)

Einsatzgruppe B reported it was killing 500 people a day.

The Einsatzgruppen were brutally effective in their diabolical mission wherever they roamed such as in Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, Latvia, Estonia, western Russia, and even North Africa. By the end of 1941, for example, 80% of Lithuanian Jews had been executed. The murders went on and on and on. The Nazis, as in other areas, kept their own meticulous records of their butchery. The historian N. Stone notes:

In February 1942, Einsatzgruppen A in the Ukraine reported, with that mania for exactitude that distinguished the SS even at its most animal, that it had executed '1,064 commissars, 56 partisans, 653 mental cases, 44 Poles, 28 Russian prisoners of war, 5 gypsies, 1 Armenian and 136,421 Jews'.

(Stone, 160)

Einsatzgruppe A commander, Franz Stahlecker, even provided his superiors with a helpful map of exactly where and how many people had been murdered by his group. Eichmann, ever proud of his work, himself estimated that, in total, the Einsatzgruppen were responsible for 2 million deaths. This may be an exaggeration as Eichmann was keen to impress his superiors with his efficiency, but it is also true that a precise total figure can not be known since many deaths in Nazi reports were referred to through euphemisms like "resettled". Eichmann, in reference to the victims of the Nazi death camps and Einsatzgruppen combined, once stated, "I will leap laughing to my grave because the feeling that I have five million people on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction" (Boatner, 150). Eichmann later revised this figure to six million. The very fact that no precise figures of how many people were murdered is, if anything, indicative not only of the secrecy of these operations but also of the enormous scale of these Nazi killing sprees.

Eyewitness Accounts

Victims of the Einsatzgruppen were often forced at gunpoint to dig their own mass graves before they were shot. It is only through the miraculous survival of those who were not fatally shot but were considered so by their executors that the actions of Einsatzgruppen became more widely known after the war. Another method of execution was gassing victims using large specially-converted trucks (similar to furniture vans) where the exhaust pipe of the vehicle was fed back into the truck where up to 70 people were confined. The trucks seemed innocuous from the outside, and victims entered them without knowing their dreadful fate. It took up to 15 minutes for the carbon monoxide gases to kill the victims, although, as Einsatzgruppen officers later testified, death was usually caused by suffocation without first falling asleep. The SS department responsible for these mobile execution vehicles was known as simply T4.

Avraham Aviel, a Polish Jew and survivor of a mass execution, gives the following account of his experience in May 1942:

We were all brought close to the cemetery at a distance of eighty to a hundred metres from a long, deep pit. Once again everybody was made to kneel. There was no possibility of lifting one's head. I sat more or less in the centre of the town people. I looked in front of me and saw the long pit then maybe groups of twenty, thirty people led to the edge of the pit, undressed probably so that they should not take their valuables with them. They were brought to the edge of the pit where they were shot and fell into the pit, one on top of another.

(Holmes, 319)

Karl Wolff, a colonel in the Waffen-SS, also describes this method of execution on an occasion on the Eastern Front when the head of the SS Heinrich Himmler was personally present:

Not to go into too unnecessary details an open grave had been dug and into this these partisans, who had not even been condemned by a proper hearing but had merely been taken by numbers, they had to jump into this and lie face downwards, and sometimes when already two or three rows had been shot they had to lie in the people who were already shot and then they were shot from the edge of the grave…

(Holmes, 321)

Hermann Gräbe was a German engineer who witnessed an atrocity committed by the Einsatzgruppen. The date was 2 October 1942, the place Dubno in Ukraine. Gräbe's statement was used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials:

I drove to the site…and saw near it great mounds of earth, about 30 metres long and 2 metres high. Several trucks stood in front of the mounds. Armed Ukrainian militia drove the people off the trucks under the supervision of an SS man…All these people had the regulation yellow patches on the front and back of their clothes, and thus could be recognised as Jews…My foreman and I went directly to the pits. Nobody bothered us. Now I heard rifle shots in quick succession from behind one of the earth mounds. The people who had got off the trucks – men, women, and children of all ages – had to undress upon the order of an SS man who carried a riding or dog whip. They had to put down their clothes according to shoes, top clothing and undergarments. I saw heaps of shoes of about 800 to 1000 pairs, great piles of under-linen and clothing. Without screaming or weeping these people undressed, stood around in family groups, kissed each other, said farewells…During the fifteen minutes I stood near, I heard no complaint or plea for mercy…An old woman with snow-white hair was holding a one-year-old child in her arms and singing to it and tickling it…The parents were looking on with tears in their eyes. The father was holding the hand of a boy about ten years old and speaking to him softly; the boy was fighting his tears. The father pointed to the sky, stroked his head and seemed to explain something to him. At that moment the SS man at the pit started shouting something to his comrade. The latter counted off about twenty persons and instructed them to go behind the earth mound…I walked around the mound and found myself confronted by a tremendous grave. People were closely wedged together and lying on top of each other so that only their heads were visible. Nearly all had blood running over their shoulders from their heads. Some of the people shot were still moving…I estimated that it [the pit] already contained about a thousand people…The people, completely naked, went down some steps, which were cut in the clay wall of the pit, and clambered over the heads of the people lying there to the place which the SS man directed them. They lay down in front of the dead or wounded people; some caressed those who were still alive and spoke to them in a low voice. Then I heard a series of shots. I looked into the pit and saw that the bodies were twitching or the heads already lying motionless on top of the bodies that lay beneath them. Blood was running from their necks. The next batch was approaching already.

(MacDonald, 49-51)

Lieutenant-general Otto Ohlendorf, a German SS commander of Einsatzgruppe D operating on the Eastern Front (specifically, in southern Ukraine and the Crimea), gave the following summary of how people were killed as part of his testimony at the Nuremberg trials:

The Einsatz unit would enter a village or town and order prominent Jewish citizens to call together all Jews for the purpose of resettlement. They were asked to hand over their valuables and shortly before execution to surrender their outer clothing. They were taken to the place of execution, usually an anti-tank ditch…Then they were shot, kneeling or standing, by firing squads in a military manner and the corpses thrown into the ditch.

(Hite, 413)

When asked on the witness stand how many people his unit had killed, without hesitation Ohlendorf replied, "In the year between June 1941 to June 1942 the Einsatzkommandos reported ninety thousand people liquidated" (MacDonald, 52). When asked if his men questioned the legality of their orders, Ohlendorf replied, "…the order was issued by the superior authorities, the question of legality could not arise in the minds of these individuals, for they had sworn obedience to the people who had issued the orders…No one could disobey – the result would have been a court martial with a corresponding sentence" (ibid, 53).

When the Einsatzgruppen's main work was superseded by the death camps like Auschwitz, Bełżec, and Sobibor, where victims were gassed in purpose-built chambers and then cremated, the killings grew to terrifying numbers. It was not until the USSR's Red Army began to push back and advance on Germany's eastern frontiers that the Einsatzgruppen members began to think a little for their future. To hide the atrocities the Einsatzgruppen had committed, mass graves were dug up, and the bones of victims were put through crushing machines or burned using petrol. Concentration camp prisoners were forced to do this terrible work and then were themselves executed to ensure secrecy. Despite the efforts to conceal their crimes, the Einsatzgruppen would be brought to justice.

The Einsatzgruppen Trials

As the historian R. Holmes remarked, "the Nazis devoted enormous resources and ingenuity to killing millions of helpless people who posed no military, political or economic threat whatever, and they continued doing so until the last days of the war" (Holmes, 314). Only when Germany surrendered in May 1945 did the executions finally stop. And it was only then that justice could be pursued for the victims. The Einsatzgruppen trials were part of the second phase of the Nuremberg trials – officially called the US Nuremberg Military Tribunals (NMT) – carried out from November 1946 to April 1949. 24 officers of the Einsatzgruppen were put on trial, and 14 were sentenced to death by hanging, amongst them was Ohlendorf. Ten of the 14 subsequently had their sentences commuted to lengthy prison terms. More importantly, perhaps, thanks to the trials and the publicity surrounding them, the world was now fully aware of these terrible atrocities.