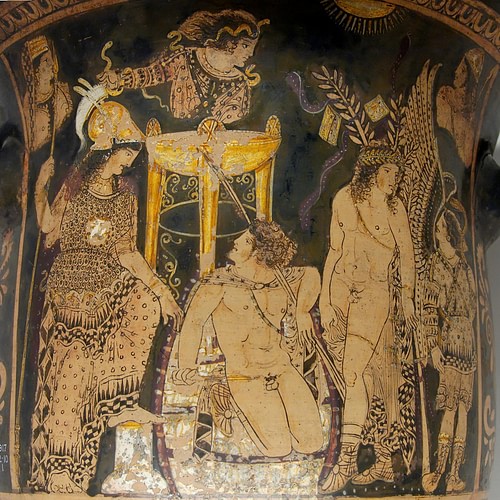

Electra is a Greek tragedy written by the playwright Euripides c. 420 BCE. It retells the classic myth concerning the plotting of Electra and her brother Orestes to kill their mother and her lover. This version of the story should not be confused with the play of the same name by his fellow playwright, Electra by Sophocles. Classicists are unsure which of the two plays was written first. As with most of plays of the period, the audience was well aware of the story of Agamemnon's return from the Trojan War and his death at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus.

In Euripides' version of the story, Electra has been thrown out of the royal house and married to a poor farmer to prevent her from having children of high enough status to avenge Agamemnon's death. One day two strangers arrive at her door. Although they do not identify themselves, they are in reality Electra's exiled brother Orestes and his friend Plyades. When she invites them in and tells them her story, an old servant recognizes Orestes from a childhood scar. Together Electra and Orestes plot their revenge. Electra sends word to her mother that she has given birth and wishes Clytemnestra to see the baby. Meanwhile, Orestes and Plyades find Aegisthus hunting and kill him, returning to Electra's home with the body. When Clytemnestra arrives, she is murdered, too. At the end of the play, Clytemnestra's deified brothers Castor and Pollux (Polydeuces in the play) appear and tell them they must cleanse their souls of their crime. Electra is to marry Plyades and leave her home while Orestes (who is being pursued by the Furies) must face a trial; he suffers a fate similar to that in Aeschylus' Oresteia.

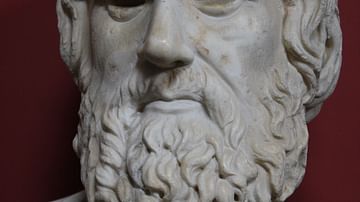

Euripides

Very little is known of Euripides' early life. He was born in the 480s BCE on the island of Salamis near Athens to a family of hereditary priests. Although he preferred a life of seclusion, alone with his books, he was married and had three sons, one of whom became a minor playwright. Many suspect that the son may have completed Iphigenia in Aulis after his father's death in 406 BCE. Unlike Sophocles, Euripides played little or no part in Athenian political affairs; the one exception was a brief diplomatic mission to Sicily. Of his 92 plays, 19 still exist in their entirety. The poet made his debut at the Dionysia in 455 BCE, performing over 22 times, only to win his first victory in 441 BCE. Unfortunately, his participation in these Greek theatre competitions did not prove to be very successful with only four victories; a fifth came posthumously for Iphigenia in Aulis. In contrast, Sophocles won over 24 times.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle called Euripides the most tragic of all of the Greek poets. Classicist Edith Hamilton in her book The Greek Way agreed when she wrote that he was the saddest of the poets, a poet of the world's grief. “He feels, as no other writer has felt, the pitifulness of human life, as of children suffering helplessly what they do not know and can never understand.” (205) With the war against Sparta still waging, Euripides left Athens in 408 BCE at the invitation of King Archelaus to live the remainder of his life in Macedonia. Some believe his disappointment at the Dionysia drove him to leave Athens. Although often misunderstood during his lifetime and never receiving the acclaim he deserved, he became one of the most admired poets long after his death, influencing not only Greek literature but Roman playwrights. The Greek comedy playwright Aristophanes often parodied him in many of his plays. It is said that children would learn language and grammar from both Homer and Euripides.

Cast of Characters

- Electra

- Farmer

- Clytemnestra

- Orestes

- Plyades

- Chorus of Argive Women

- Old Man

- Messenger

- Castor and Polydeuces

The Play

The play opens in front of a small farmer's cottage near the Greek city of Argos. Next to the house is an altar to the Greek god Apollo. The farmer - Electra's husband - speaks aloud of the fallen king Agamemnon and his children Electra and Orestes. He relates how young Orestes was “snatched away and grew up in the land of Phocis” (194). A price was then placed on his head.

Electra kept on waiting in her father's house, but when the burning season of young ripeness took her then the great princes of the land of Greece came begging her bridal. (194)

As a precaution she was given to the farmer as his wife; however, she remained untouched. “I would feel ugly touching the daughter of a wealthy man and violating her.” (195) When Electra exits her house, she acknowledges her husband who never takes advantage of her.

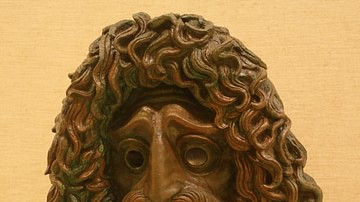

As the farmer leaves to tend his fields and Electra returns to the house, Orestes and his close friend Plyades enter and stand by the altar. Speaking of his mother's lover Aegisthus, he tells Plyades:

He killed my father - he and my destructive mother. I come from secret converse with the holy god to this outpost of Argos - no one knows I am here - to counterchange my father's death for death to his killers. (196)

Not knowing he is outside his sister's home, he hopes to find his sister. Hearing someone coming (Electra), he and Plyades hide. A distraught Electra addresses the chorus of Argive peasant women:

Not one god has heard my helpless cry or watched of old over my murdered father. Mourn again for the wasted dead, mourn for the living outlaw somewhere prisoned in foreign lands, passing from one laborer's hearth to the next though born of a glorious sire. (200)

She feels she has wasted her life in a peasant's hut. As she speaks, Orestes and Plyades appear from their hiding spot. Not recognizing her brother, she assumes the two strangers to be criminals, but Orestes (who does not identify himself) assures her that he would never hurt her. However, Electra, still fearful, asks why the two men were hiding, sword in hand. Realizing he is speaking to his sister, Orestes eases her distress: “I have come to bring you a spoken message from your brother…” (201) He tells her that her brother is alive. She is curious and asks: “Where is he now, attempting to bear unbearable exile?” Has he sent her a message? Orestes tells of her brother's concern for her: “Your brother's life and father's death both bite your heart.” (202)

Orestes is curious why she lives in a peasant's house. She admits that her wedding was “a wedding much like death” (203). However, her husband respects her and has never been violent or touched her. She further explains that the wedding - in Aegisthus' mind - would bring worthless sons. They would be too weak for revenge. Orestes wonders how - if her brother returns - he could help. She responds, “By being just as daring as once his enemies were” (208). Electra admits she would not know her brother if she saw him but she knows someone who would, the man who saved him from death, Agamemnon's tutor. As they speak Electra's husband appears and inquires about the two strangers. She eases his curiosity and says they bring news of Orestes. The farmer invites them into his home. Orestes replies:

This fellow here is no great man among the Argives, not dignified by family in the eyes of the world - he is a face in the crows, and yet I choose him champion. (209)

Electra sends the old farmer to find her father's servant. Shortly, an elderly man arrives with food. When he sees Electra, he tells her that he has been at Agamemnon's tomb where he found a lock of hair. He believes Orestes has been at the tomb, but Electra is doubtful. The old man tries to convince her that her brother is back from exile; he then asks to see the two strangers who have brought news of Orestes. As they speak, Orestes and Plyades exit the house and join them. Electra tells them that this is the man who saved Orestes from Aegisthus and certain death. The old man stares at Orestes and recognizes the stranger as Orestes from “The scar above his eye where he once slipped and drew blood as he helped you chase a fawn in your father's court.” (217) Orestes finally admits his true identity:

I am your sole brother and friend. Now if I catch the prey for which I cast my net! I'm confident. Or never believe in the gods' power again if evil can still triumph over good. (218)

The old man tells Orestes that he must kill his mother and her lover Aegisthus who lives in fear of Orestes' return. He says that Aegisthus is often in the meadow where he grazes his horses and, with only a few servants, he will be there sacrificing a bull for a feast. Orestes would have no trouble approaching him. As for Electra, her plan is to have the old man to go to Clytemnestra and inform her that her daughter is in bed after bearing a son.

She will come, of course, when she hears about the birth. ... She will come; she will be killed. All that is clear. (222)

She tells the old man to help Orestes but first go to Clytemnestra. He agrees and then promises to show Orestes where he can find Aegisthus. They exit, leaving Electra alone at home. As she awaits the appearance of her mother, a messenger arrives letting her know that Orestes is victorious and Aegisthus is dead. He tells her of the meeting between her brother and Aegisthus. The two men spoke and when Aegisthus bent over, Orestes killed him.

[Orestes] stretched up, balanced on the balls of his feet, and snatched a blow to his spine. The vertebrae of his back broke. Head down, his whole body convulsed, he gasped to breathe, writhed with a high scream, and died in his blood. (229)

Orestes turned to the servants and told them “I have only paid my father's killer back in blood” (230). Orestes soon arrives at Electra's home with Aegisthus' corpse. She speaks to the corpse of her mother's lover:

You ruined me, orphaned me, and him too, of a father, we loved dearly, though we had done no harm to you to cuckoldry though she had stained our father's bed adulterously. (232)

Orestes changes the subject to their mother. Fearing reprisal, he asks, “How can I kill her when she bore me and brought me up?” (234) Electra makes an effort to convince him that killing their mother is only avenging their father. Reluctantly, he agrees. About that time Clytemnestra arrives at Electra's home. Electra coolly greets her: “You threw me out of home like a war captive.” (237) Her mother tells of Agamemnon's arrival with Cassandra (Priam's daughter) and the sacrifice of Iphigenia. After her attempt to explain Agamemnon's death, she gives Electra permission to speak freely. She says:

Of all Greek women, you were the only one I know to hug yourself with pleasure when Troy's fortunes rose, but when they sank to cloud your face in sympathy you wanted Agamemnon never to come home. ... If murder judges and calls for murder, I will kill you - and your son Orestes will kill you - for Father. (239)

Electra then invites her mother into the house to see her son. Shortly, Clytemnestra cries out. She is dead. As Electra and Orestes rejoice, the Dioscuri (Castor and Polydeuces) appear above the house. They are the twin brothers of Clytemnestra and the sons of Zeus. Castor addresses the fate of both Electra and Orestes. Electra is to marry Plyades, leave Argos, and go to Athens to stand trial where they will be found not guilty. Orestes is forbidden to ever see his sister again. He, too, must stand in judgment: “I am forced from my father's house. I must suffer foreigners' judgment for the blood of my mother.” (248) Electra holds her brother. “… the curses bred in a mother's blood dissolve our bonds and drive us from home.” (248) They depart.

Conclusion

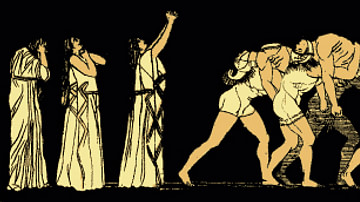

The story of the murder of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus was written about in three different plays: Aeschylus' Libation Bearers (part of his Oresteia), Sophocles' Electra, and Euripedes' Electra. All three tell a different version of the same events: Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus have killed Agamemnon. Years later, Electra waits for the return of her exiled brother Orestes so they can seek revenge against their mother. While the story is the same, the manner in which the duo meets their demise varies.

In Aeschylus' version, Orestes and his friend Plyades meet Electra and tell her he has been commanded by the oracle of Apollo to kill their mother. The two pose as travelers and arrive at the palace door. They tell Clytemnestra of the death of Orestes. When Aegisthus is summoned to the palace, the two kill him and then turn on Clytemnestra. Orestes is chased out of Argos by the Furies and the story is completed in Eumenides.

In Sophocles' version, a second sister, Chrysothemis, enters the picture but she refuses to be part of any plot. Similar to Aeschylus, Orestes and Plyades pose as travelers with news of Orestes' death. Carrying an urn into the palace, they kill Clytemnestra. When Aegisthus arrives at the palace, he, too, is murdered. In both versions, Electra does not seem to be an active participant in the murders.

Finally, in Euripides' story, Orestes and Plyades arrive at Electra's home and are soon identified by an old servant. A scheme is quickly plotted. Orestes and Plyades find Aegisthus out hunting and kill him, taking his body to Electra's home. Electra, who is married in this version, lures her mother to her home with news of a baby and, with Orestes' help, kills her. In this account, however, Orestes is initially reluctant to kill Clytemnestra. Hounded by the Furies, Orestes is forced to leave Argos while Electra is told she must marry Plyades and leave.