The electrical telegraph was invented in 1837 by William Fothergill Cook (1806-1879) and Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875) in England with parallel innovations being made by Samuel Morse (1791-1872) in the United States. The telegraph, once wires and undersea cables had connected countries and continents, transformed communications so that messages could be sent and received anywhere in just minutes.

Telegraph Pioneers

The idea of sending signals from one distant place to another has been in use since antiquity, notably with towers using fire beacons. Ships have long used a system of flags (semaphore) to communicate beyond shouting distance. These methods, though, were limited to only very important communications, for more mundane messages people had to use horse-riding messengers that could take several days or even weeks to reach their intended recipient.

The Italian Alexander Volta (1745-1827) invented the electric battery in 1800, necessary for a telegraph machine to be operated anywhere. Then the Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851) created the first electromagnet in 1825. Ørsted's discovery that an electrical current flowing in a conductor can create a magnetic field – which he noted when observing the effect on a magnetic compass on his desk – was crucial to the telegraph machine since this was the answer to the problem of how to make electrical impulses visible in the form of a moving needle. The French physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) worked to create a theory that explained the relationship between an electrical current and magnetism. The first electric motor was developed by the Englishman Michael Faraday (1791-1867) in 1821. With all of these scientific discoveries put together, inventors now had the theoretical means to send electrical impulses through a wire and then see the effect at the other end. The trick was just how to create a working machine capable of sending and receiving these impulses over long distances and a code by which such impulses could be transformed into words.

Cook & Wheatstone

The first commercial telegraph machine was invented by two Englishmen working together: William Fothergill Cook and Charles Wheatstone. The first version of their telegraph, patented in 1837, had 20 letters on a diamond-shaped board with five needles and six wires. The six letters of the alphabet missing were simply omitted from messages. The message received by the machine was indicated by the slight movement of any two of the needles to the left or right. This movement was caused by electrical impulses being sent down the telegraph line connected to the sender's machine. The machine operator gave the machine electrical power by using a winding mechanism that energised the connected battery. Although the inventors first demonstrated to the directors of the London to Birmingham railway line that their incredible machine did indeed work, it did not convince their business audience to buy the machines. The first successful commercial use of the machine, then, was for the Great Western Railway in 1838, used between Paddington Station and West Drayton, a distance of 21 kilometres (13 miles). Short messages could now be sent quickly and were first used on the railways to communicate instructions to drivers and stations.

The telegraph wires connecting machines – copper wires set within a block of wood – were placed underground within a protective steel tube or conduit, but over time it was noticed that the wires deteriorated. An alternative solution was found which was to hang the wires in the air using poles. Another development was to reduce the fives needles of the machine to just one connected to two wires. In 1843, this new machine was used successfully on the now-extended rail line from Paddington to Slough in Berkshire. The machine was quickly adopted by other railway companies at home and abroad, including by the British East India Company from 1851. In 1867, the first machine to indicate numbers as well as letters was used. The electric telegraph was especially useful for riskier stretches of railway lines such as tunnels. A Cook and Wheatstone machine was installed on the Blackwall Tunnel Railway in 1840, for example. Train drivers could now carry a portable telegraph machine and, if necessary, plug it into a junction box by the side of the track to contact the nearest station.

Morse Code

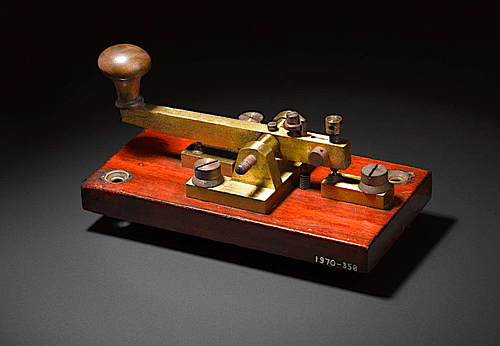

As with many other inventions in the Industrial Revolution, different types of telegraph machine were developed independently in different countries. Telegraph communication made a real step forward when Samuel Morse of Massachusetts, with the often uncredited assistance of Alfred Vail (1807-1859) and Leonard Gale (1800-1883), first put his Morse code into action in 1844. The code represented letters using combinations of dots and dashes, that is short and long electrical impulses created by briefly pressing down on a key to complete an electrical circuit. While Cook and Wheatstone had used the movement of needles, Morse effectively used sound to register the messages.

Morse was a successful portrait painter, but he had been driven to create a system of instant messaging in the late 1830s by an unfortunate incident involving his wife. Morse was in Washington when he heard news of his wife's death at their home in New Haven. By the time Morse had returned home, his wife had already been buried. If Morse had received news earlier, first of his wife's illness and then death, he might have been able to attend her funeral.

Morse demonstrated his device before the US Congress in 1843 and did so with success. Morse and Vail were awarded $30,000 to establish a working telegraph system. The site chosen was between Baltimore and Washington D.C. where just over 60 kilometres (37 mi) of telegraph line were hung up on poles set in the ground. The first message was sent along this line on 24 May 1844. The message read: "What hath God wrought!" Now that the telegraph had been proven to work in the real world, the system was adopted across the United States. The Morse code, as it became known, was adopted in Europe, too. In 1856, the Western Union Telegraph Company was created, and by 1866, it ran 4,000 telegraph offices in the United States.

Further Developments

Telegraph operators soon became experts at decoding the dots and dashes in received messages so that they could directly write down the words intended. To assist operators to distinguish letters, the machines were deliberately given a louder clicking noise. There were some attempts to make the telegraph a device that could be used by someone without knowing a code – Cook and Wheatstone developed a machine that used a dial of letters and matching buttons – but the problem was these devices were much slower to use (around 15 words per minute) than the code telegraph.

Many inventors continued to tinker with the idea of the telegraph machine, an indication, if anything, of the tremendous potential of the device. In 1850, the Scotsman Alexander Bain (1810-1877) invented a telegraph machine that could send and receive messages using perforated strips of paper. This machine, known as the chemical telegraph, read the holes in the chemically-treated paper and made a corresponding electrical impulse. Wheatstone made a similar device in the 1850s. In 1854, the Austrian Thomas John invented a machine that could convert a telegraph message into print using ink on strips of paper. The design was manufactured by the German company Siemens and Halske and was popular across Europe. In 1855, the British-American professor of music David E. Hughes (c. 1829-1900) invented a machine that looked rather like a miniature piano with 26 keys, one for each letter of the alphabet. The sending and receiving machines were synchronised by a clockwork mechanism so that the receiver could write down the letters of the received message.

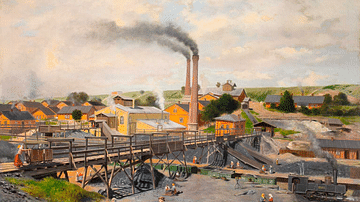

The giant steamship SS Great Eastern, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859), laid the first cross-Atlantic telegraph cable in 1866, and this now allowed fast intercontinental communication. More ocean cables were soon laid to other continents. By the 1890s, anywhere in the British Empire, from Canada to Hong Kong, could be reached in an instant thanks to the telegram system. By the end of the 19th century, England alone had 25,000 km (15,500 mi) of telegraph wires which were carrying 400 million telegraph messages each year. In less than 50 years, the world seemed a little smaller and life a lot faster.

Consequences of the Telegraph

As the telegraph system was adopted across the British railway network, so for the first time it was possible to have a universal time when previously town clocks had all varied. Consequently, the telegraph made Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) possible. Post offices began to offer the service of sending telegrams to private individuals for a small charge. Information could be sent wherever there were telegraph machines, meaning that news of events spread far quicker than previously. The speed of telegraph communication was also particularly useful for certain professions. The military trialled electrical telegraphs with success during the Crimean War (1853-6). Roving journalists could send reports back to their editorial offices as, for the first time, the public followed world events on a daily basis.

The police found the telegraph a useful tool in crime prevention. An officer could alert colleagues far away of criminal activity and even help to capture escaping criminals. One famous case really highlighted the telegraph's potential to the general public. One John Tawell was suspected by the police of having committed a murder. On New Year's Day 1845, police knew that Tawell was travelling on a certain train, and so they sent a telegram to colleagues at Slough Station to have Tawell arrested on his arrival there. Tawell was captured, tried, and hanged for his crime.

Shipping also used the telegraph, eventually allowing passengers at sea to contact friends and family on shore. The telegraph could also be used in times of distress. The first use of the SOS Morse code signal (3 dots, 3 dashes, and 3 dots) by a liner was sent by wireless operator John George Philips on RMS Titanic after the ship struck an iceberg in the Atlantic in April 1912.

There were some downsides to the invention, particularly for the operators. Repeatedly pressing down on morse keys to send messages, especially for post office workers, often resulted in a repetitive stress injury known as 'telegrapher's paralysis' or 'glass arm'. The very nature of the Morse code meant that sometimes messages were incorrectly decoded. As people paid per word for telegram messages, this meant that messages were often shortened or certain words omitted which sometimes led to confusion over what exactly the sender had intended to say.

The arrival of the telephone, first patented in 1876 by Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922), challenged and then gradually replaced the telegraph system. Telephones offered the great advantages that one could hear a recognizable voice, misunderstandings were far less likely, and knowledge of a code was unnecessary.