Empedocles (l. c. 484-424 BCE) was a Greek philosopher and mystic whose work harmonized the philosophies of Parmenides (l. c. 485 BCE), Heraclitus (l. c. 500 BCE), and Pythagoras (l. c. 571 to c. 497 BCE) in presenting a unified vision of unchanging reality in which change was possible. He is the first to synthesize the Pre-Socratic philosophical systems.

Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) would do so later in his famous summaries but Empedocles not only synthesized the systems but created from them his own unique vision. His work consisted of combining radically different philosophical beliefs into a system where the changeless vision of Parmenides worked in concert with the constant change of Heraclitus and Pythagorean mysticism while also addressing the “seed theory” of Anaxagoras (l. c. 500 to c. 428 BCE), and the monotheism of Xenophanes of Colophon (l. c. 570 to c. 478 BCE). His work influenced the development of the concept of the atomic universe by Leucippus (l. c. 5th century BCE) and Democritus (l. c. 460 to c. 370 BCE), and he is also thought to have been the teacher of the sophist Gorgias (l. c. 427 BCE), thereby encompassing almost all the works of the Pre-Socratics.

Empedocles was the first to define the four elements of earth, air, fire, and water as material causes of existence which operated within a universe governed by two efficient causes, Love and Strife, which unified and destroyed, respectively. The elements were bound together by attraction (Love) and separated by opposition (Strife) but were themselves changeless in nature. In this way, he was able to reconcile Parmenides with Heraclitus. Just as the unchanging elements took different forms, so did the souls of humans, incorporating Pythagoras’ concept of the transmigration of souls (reincarnation) while Xenophanes’ beliefs are incorporated in the claim that the Divine is nothing like people have supposed and Anaxagoras’ concepts are addressed in that nothing in nature can come from what it is not.

Empedocles also incorporated into his vision the claims of the first three Pre-Socratic philosophers Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE), Anaximander (l. c. 610 to c. 546 BCE), and Anaximenes (l. c. 546 BCE) who claimed water, “creative force”, and air as the First Cause of existence, respectively. Empedocles was regarded as divine during his life and was believed to have been taken bodily to heaven, never experiencing death, though detractors seem to have started the famous legend that he leapt into a volcano to prove he was a god. Today he is regarded as one of the most significant (and, by some scholars, the paragon) of the Pre-Socratic Philosophers.

Pre-Socratic Philosophers

The early Greek thinkers are known by the modern designation Pre-Socratic Philosophers because they lived and taught before the time of Socrates of Athens (l. 470/469-399 BCE), though some were his contemporaries. Although they would come to address many philosophical issues, their initial focus was on defining the First Cause of existence without reliance on the explanation provided by Greek religion. Their works have been lost and their thoughts preserved in fragments cited by later writers. It is a testimony to Empedocles’ wide influence that more of his work was preserved than any of the others.

The fragments of Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes deal primarily with establishing the First Cause while Pythagorean concepts ranged further. Pythagoras himself wrote nothing down and his beliefs were finally committed to writing by the Pythagorean Philolaus (l. c. 470 to c. 385 BCE). Xenophanes of Colophon broke with established religion by claiming that it did not accurately depict the Divine which did not consist of many super-human deities but a single God who had nothing in common with humanity.

This line of thought, that the Divine was One, inspired Parmenides and his Eleatic School (so-called because it originated in Elea) who maintained that reality was of a single, unified, substance in which all life participated and so change was an illusion because multiplicity was inconsistent with unity. Sense perception informed people that they were born, aged, and died but this was only appearance and did not reflect the true essence of the universe. Parmenides’ claims concerning the unreliability of the senses were then proven mathematically by his student Zeno of Elea (l. c. 465 BCE) but all of this was rejected by Heraclitus of Ephesus who argued for fire as the First Cause and the essence of life as change.

To Heraclitus, the world operated through constant clashes of opposites – such as day and night – which embodied transformation and so change was life, not just a part of life, but life itself. This thought inspired Anaxagoras and his “seed theory” which claimed nothing can come from its opposite, everything must come from something of its own nature, and this “something” was particles (“seeds”) which held the essence of a particular thing. Hair, for example, could not grow from something not-hair and so the essence of hair had to be present in a human being for there to be hair.

Empedocles’ Life & Work

This was the body of philosophical work Empedocles had before him when he began his own inquiries. How or why he became interested in philosophy is unknown. His only “biography” is given by the historian Diogenes Laertius (l. c. 180-240 CE) who never cites his sources, repeats legend as fact, and often confuses names of places and people. Even Empedocles’ dates are not agreed upon, ranging from c. 494 to c.434 BCE, c. 492-432 BCE, or, the most commonly cited, c. 484-424 BCE. He was a native of Acragas (modern Agrigento), Sicily, and came from a noble family of wealth.

His grandfather was a horse breeder and champion at the Olympic Games in horse-racing in 496 BCE. His father’s name was either Meton or Exaenetus and he provided Empedocles with a good education. In keeping with the traditional model of the time, this would have involved sending the boy to school at some intellectual center where he would have learned the arts of public speaking and politics – and it is possible this was the course Empedocles followed at first – but he is only cited as a student of philosophers who did not teach these subjects including Anaxagoras, Anaximander, Pythagoras, Parmenides, and Xenophanes.

Based on his writings, he was well-versed in the mystery religion of Orphism, focused on the legendary musician Orpheus and emphasizing the reality of life after death. He is said to have been involved in politics in Acragas and to have routinely sided with the poor, even rejecting leadership of the city when it seemed to mean agreeing with the wealthy elite. If this is true, it lends some weight to the claim made by Diogenes Laertius that it was Empedocles who first made Pythagorean beliefs public as it would be in keeping with his egalitarian leanings to take the “secret knowledge” of the elite Pythagoreans and share it with everyone. It is generally understood, however, that it was Philolaus who first offered Pythagorean ideas to the public.

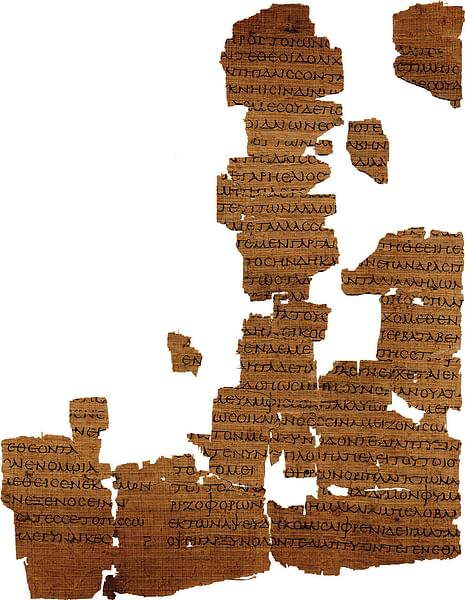

Empedocles’ fragments all come from two works (or a single, long work with two sections), On Nature and the Purifications. On Nature addresses cosmogony and the place of humanity in the universe while the Purifications is a mystical work drawing on Pythagorean and Eleatic principles while harmonizing those of other philosophers. Aside from these, other shorter works, such as a hymn to Apollo, have been attributed to Empedocles but there is no scholarly consensus on this. In both works, Empedocles displays ample knowledge of the Pre-Socratic philosophers as noted by scholar Forrest E. Baird:

Empedocles was the first great synthesizer of the history of philosophy. Around 450 BCE, a full century before Aristotle’s summation, Empedocles tried to find a place in his thought for all the major contributions of his predecessors. By explaining generation and destruction, if not all change, in terms of mixture and separation, Empedocles sought to reconcile Heraclitus’ insistence on the reality of change with the Eleatic claim that generation and destruction are unthinkable. (31)

Empedocles did not simply repeat the claims of his predecessors and contemporaries, however, but created a completely new system from them which he then preached as a means to personal enlightenment. He is said to have dressed himself in purple robes, worn golden sandals and had the ability to perform miracles such as raising the dead, curing a town of the plague, and redirecting the winds and waters. He, himself, is said to have claimed he was divine and there are passages in his works that certainly suggest this.

Empedocles’ Philosophy

Although the subject is still debated by scholars, it seems that both of Empedocles’ works were originally a single piece. Scholar Gordon Campbell writes:

In 1990 the first ancient papyrus fragments of Empedocles were rediscovered at the University of Strasbourg and were published in 1999…Among other important new information they give about Empedocles’ philosophy…the longest of the new fragments was found to be a continuation of the longest of the previously known fragments and thus now the two together form a continuous text…it now seems very likely that Empedocles introduced the themes of sin and purification early on in the physical poem. In fact, in can now be argued that all of the fragments of the Purifications can be accommodated in the early part of book one of On Nature. (3)

Empedocles addresses On Nature to his student Pausanias (obviously not the famous 2nd century CE geographer) and, interpreting both his works as concerning the nature of the universe and one’s place in it, explains how reality can be a single, constant unity while still allowing for multiplicity and change. The four elements are eternal and unchanging in their nature – water will always be water whether it is found in a stream, ocean, bath, or cup – but change is possible in the form water takes. Humans might discover a mountain spring and declare this is the origin of a valley’s river but the spring and the river are of the same essence, the water is simply in different forms and volume.

The four elements appear to humans as distinct from each other but all share in the same divine essence and Empedocles associates them with four divine figures – Zeus (fire), Hera (air), Aidoneus (a king associated with Hades, earth), and Nestis (another name for Persephone, wife of Hades, water). Empedocles considered these the roots, or essence, that inform being but claims that what arises from these roots does not actually “come into being” because, in essence, it has always existed:

When these [elements] have been mingled in the form of a man, or some kind of wild animal or plant or bird, men call this “coming into being” and when they separate, men call it “evil destiny [passing away]. This is established usage and I myself assent to the custom [but] Fools! They have no far-reaching thoughts who imagine that what was not before can come into being or that anything can perish and be utterly destroyed. For to come to be out of what is utterly nonexistent is inconceivable and it is impossible and unheard of that what is should pass away. For it will always be, wherever you put it…there is no real “coming into being” of any mortal creature, nor any end in wretched death, but only mingling and separation of what has been mingled, and “coming into being” is merely a name given to them by men. (DK 31B.8-12/Robinson 157-158)

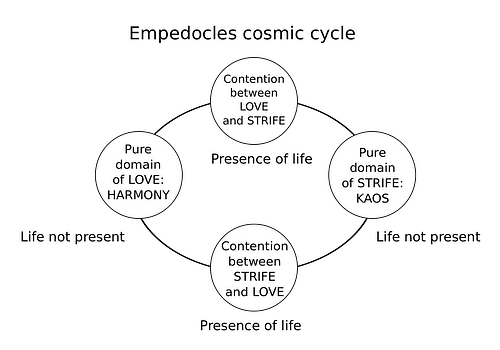

The universe, of a single, unchanging essence – of which all things are a part – is held in form by Love, which attracts and binds, and is whole until Love’s power gives way to Strife which breaks the bonds and allows for differentiation of form – but each “form” still retains the same essence. When Strife’s dominance then gives way again to Love, all is bound up again. Birth, age, and death, then, are simply a change in form of an eternal essence. As Empedocles’ puts it:

A two-fold tale I shall tell: at one time it [existence] grew to be one only from many and, at another again, divided to be many from one. There is a double birth of what is mortal, and a double passing away; for the uniting of all things brings one generation into being and destroys it, and the other is reared and scattered as they are again being divided. And these things never cease their continuous exchange of position, at one time all coming together into one through Love, at another again being borne away from each other by Strife’s repulsion. (DK 31B.17/Robinson, 159/ Campbell, 6)

Human beings, plants, and animals were born from the earth as Strife caused differentiation in form and all these pass back into eternal essence as Love exerts its influence and draws back into the One the essence that has been separated from it. Death, therefore, is not the end of life but only a transformation and each person who is supposed to “be no more” has only left one form to assume another. In this, Empedocles draws upon Pythagoras’ concept of the transmigration of souls and claims that every person now living has, at one time or another, been many different things:

For by now I have been boy, girl, plant, bird, and dumb sea-fish. (DK 117B.33/Baird, 35)

This being so, Empedocles says, one should also adhere to Pythagorean vegetarianism because each living being on earth is a spirit in corporeal form and meat-eating is a sin that separates one from the Divine, one’s own nature, and others by considering other living things as less important than oneself. To attain true understanding, Empedocles says, one should listen to him and try to understand the concepts he presents. By doing so, one will truly understand the nature of existence instead of only grasping a part of it and claiming full knowledge:

For limited are the means of grasping…and many are the miseries that press in and blunt the thoughts. And having looked at only a small part of existence during their lives, doomed to perish swiftly like smoke, they are carried aloft and wafted away, believing only that upon which as individuals they chance to hit as they wander in all directions; but every man preens himself on having found the Whole; so little are these things to be seen by men or to be heard, or to be comprehended by the mind. (Freeman, 51, fragment 2)

True knowledge of the world, Empedocles says, lies in recognizing the essential Oneness of the essence of all things, how everything and everyone is a part of the All, and understanding oneself as an eternal spirit presently occupying a human form. One’s form will eventually break down through the operation of Strife but will be gathered back into the eternal, undifferentiated essence by the attraction of Love.

Conclusion

Empedocles seems to have strongly suggested that people suffer because they have a wrong belief about the nature of existence, thinking that they are born, live, and then cease to exist at death or wander as ghosts in another realm. He maintains that, instead, one returns to essential essence after leaving the body and then returns in another form. In this, his teachings are similar to those of the Buddha (l.c. 563 to c.483 BCE) who also recognized that suffering is caused by one’s ignorance of the nature of existence. Once one grasped the true nature of reality, Buddha claimed, the truth would release one from the cycle of rebirth, death, and suffering.

As noted, more of Empedocles’ fragments are extant than those of any other Pre-Socratic philosopher and he is referenced more often by Plato than most others. Plato’s famous passage in Symposium, in which the playwright Aristophanes discusses the whole beings which were split apart and ever after search for their other half, is a direct reference to Empedocles’ concept of Love and Strife.

His concept of the unified essence of reality inspired the concept of the atomic universe advocated by Leucippus and Democritus, claiming all matter is of a single substance, but also encouraged Gorgias’ claim that there was no such thing as “knowledge”, only “opinion” and the truth of existence was ultimately unknowable. Empedocles would have disagreed with his student on this in that one only had to accept his vision to understand the universe and one’s intimate connection to its eternal essence.

(Author's Note: The DK in citation above references the Diels-Kranz system of numbering Pre-Socratic fragments included in most books on the subject)