Emperor Taizu (960-976 CE), formerly known as Zhao Kuangyin, was the founder of the Song (aka Sung) dynasty which ruled China from 960 to 1279 CE. Taizu settled for a territorially smaller but more unified and prosperous China than was seen in previous dynasties, and he made particular efforts to curb the powers of the military and bolster those of the scholar-officials within the state bureaucracy. Taizu's careful governance would ensure that his successors had the foundation upon which they could build one of the most successful dynasties in China's history.

Rise to Power

The Tang dynasty had ruled China from 618 CE with great success, but their collapse in 907 CE resulted in a sustained period of political upheaval. The once unified Chinese state was broken up into many competing political entities and so the era from 907 to 960 CE is often referred to as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (Wudai shiguo) period. One man would rise above all other military rulers in these turbulent times, the Later Zhou dynasty general-warlord Zhao Kuangyin (also spelt Guangyin).

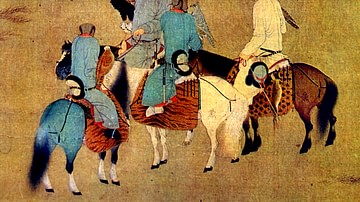

Born in 927 CE in Luoyang, Henan province, Zhao Kuangyin was the second son of an important military commander called Zhao Hongyin. The younger Zhao turned out to be a fine archer and horseman. At age 20, Zhao Kuangyin was already a commander in his own right, fighting for the Later Zhou dynasty (951-960 CE). Extending their control over much of southern China, Zhao became the foremost commander in the Zhou army. At the same time, the ruler of the Zhou died, and his son took the title but he was still a child. Consequently, in 960 CE the Zhou army endorsed Zhao as their new leader, dressed him in yellow imperial robes and confidently proclaimed him the emperor of all China.

The Emperor's Domestic Policies

Zhao Kuangyin took the reign title Taizu, meaning 'Grand Progenitor'. The emperor's first priority was to ensure he kept his own position as the most powerful man in China. To that end, Taizu introduced a rotation system for his top generals, gave many former commanders only minor positions in the new regime, and reduced the powers of those commanders in the country's 15 newly created administrative regions or circuits. Consequently, Taizu ensured that no single military leader ever became powerful enough to usurp him. As a further check on the army's power, some generals were encouraged to retire on a handsome pension, others were given gifts to gain their loyalty, and still others were simply replaced by civilian officials whenever they retired or died. The government was centralised around the court at Kaifeng and the powers of the civil service were increased as was its status compared to the military professions. Further, the civil service was tasked with overseeing the army, acting as its supervisory body. The emperor was creating a much less militaristic regime and focusing instead on a more efficient administration than had been seen in China throughout the 10th century CE.

Taizu attempted to reduce corruption and the power of the eunuchs in the imperial court and was known for his tight hold on the state purse strings. To ensure the scholar-officials did not abuse their new-found power, Taizu revived the tried and tested civil service examination system. These entry tests to the civil service ensured that at least a healthy majority of officials were selected on merit rather than their family connections or outright bribery. Finally, the emperor introduced a new law code in 962 CE with harsh penalties and punishments, especially for government malpractice. After 963 CE, to further strengthen his meritocratic system, senior officials were prohibited from making appointments based only on recommendations. All of these measures would allow the Song to get off to a good start and form the solid foundation of state management that Taizu's successors would build upon with great success.

Kaifeng

Kaifeng, located on the Wei river in northern-central China at a strategically useful meeting point of various waterways, had already been a capital in earlier dynasties and it was selected by Taizu as his capital, too. The old Tang capital at Changan had, in any case, been utterly destroyed during the fall of that dynasty. The imperial heart of Kaifeng was laid out on a precise grid pattern, an intentional design meant to reflect harmony and good governance, as noted by the emperor himself when addressing his officials:

My heart is as straightforward as all this, and as little twisted. Be ye likewise. (quoted in Dawson, 62)

Kaifeng prospered and became one of the great metropolises of the world under the Song. With a population of around one million, the city would benefit from industrialisation and was well supplied by nearby mines producing coal and iron. A major trade centre, Kaifeng was especially famous for its printing, paper, textile, and porcelain industries, the products of which were exported far and wide along the Silk Roads.

Foreign Policy

In terms of foreign policy, Taizu had his hands full defending his northern borders against the Khitan Liao dynasty (907-1125 CE) who, significantly, remained in control of the Great Wall of China. The Khitan were great horsemen and they launched so many raids into Song China that Taizu and his successors were compelled to pay their neighbours annual tribute in the form of silver and silk. Tribute was cheaper than warfare, though, and much of the silver came back again as the two cultures remained committed trading partners. In any case, Taizu was content to consolidate his grip over central and southern China, a big enough task considering the recent fragmented history of the country. In addition, officials considered that the fall of the Tang had been mostly due to their over-ambitious foreign policy. The Song would settle for a smaller but more unified and prosperous state.

Neo-Confucianism

Taizu and his successors had to deal with less tangible problems than court rivalries and foreign threats. The period saw a new political and intellectual climate which questioned imperial authority and sought to explain where it had gone wrong in the final years of the Tang dynasty. A symptom of this new thinking was the revival of the ideals of Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism as it came to be called, which emphasised the improvement of the self within a more rational metaphysical framework. This new approach to Confucianism, with its metaphysical add-on, now allowed for a reversal of the prominence the Tang had given to Buddhism seen by many intellectuals as a non-Chinese religion. Taizu himself was always keen to present himself as the classic Chinese Confucian ruler, that is a wise, benevolent, and indisputable sovereign who presided over a fixed and efficient hierarchy of power.

The Arts

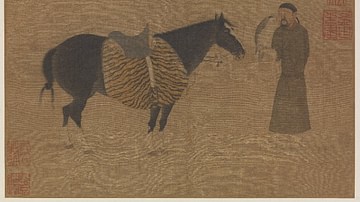

Taizu, perhaps surprisingly considering his military background, was a keen patron of the arts once he had established himself as emperor. It may have been a strategy of his to help reunify China not just militarily, politically, and economically but also culturally. The emperor promoted the idea of 'this culture of ours' (si wen). The printing of books was promoted on all three of the major religions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. An imperial library was established at Kaifeng which collected together in one place thousands of volumes of literature and histories; Taizu even ordered the collection of important silk scroll paintings and calligraphy specimens, always a highly-valued art form in Chinese culture. These efforts were amongst the first to not only produce great art but also preserve that which had been made by previous generations.

Successors & legacy

Taizu died in 976 CE, and his successor was his younger brother Taizong (r. 976-997 CE). Together, the stability of their four-decade-long rule ensured that the Song got off to the best possible start. The Song dynasty would, in fact, rule China until 1279 CE and see great developments in agriculture, trade, arts and science, although the reign was split into two periods: the Northern Song (960-1125 CE) and Southern Song (1125-1279 CE) following the invasion by the Jin state in the first quarter of the 12th century CE.